The name Stanley Kubrick is the stuff of film legend. Not only is he considered one of the most creative and influential filmmakers of all time, but there are countless wild stories about what went on behind the scenes of his movies. Everyone knows about the multiple takes that ran into the hundreds, his supposedly bullish attitude with his actors, and how his final movie might have led to his death. His later hermetic lifestyle gave birth to a mystique that would spawn many speculations and rumors about what was going on with this film genius. But there is one particularly crazy Kubrick story that doesn’t often get the attention that it most definitely deserves: the time that an English travel agent named Alan Conway pretended to be him, and even managed to fool prominent figures in the entertainment world. He gained the trust of many young men, promising them roles, financing, and professional advice, then disappeared. It was so crazy that Kubrick’s personal assistant went on to turn it into a screenplay, with John Malkovich starring as the infamous impostor.

Who Was Alan Conway?

There are two notably insightful perspectives on the wild story of Alan Conway: Andrew Anthony’s 1999 article The Counterfeit Kubrick in The Guardian, in which Conway’s own son told the journalist all about his father’s antics, and Color Me Kubrick! in Stop Smiling magazine, the first-hand account of Kubrick’s personal assistant Anthony Frewin, who saw it all from the inside and would go on to pen the script for a movie of the same name. Between them, they paint a portrait that is equal parts amusing, saddening, and downright hard to believe. It would seem there was no mad genius behind this unthinkable scam, or even any real thought at all. As his son tells it, the aptly-named Conway had lived a long life of delusion and deception that took him all over the world, leaving a trail of debt, scandal, and criminality behind him. “A man who, in his fantasies and personality swings, eluded everybody including himself,” journalist Anthony puts it. To top it all off, Conway Jr. describes his father as an abusive drunk who “terrorized me.” Clearly Conway was a complex and far from innocent character whose own family even struggled to define him.

What Did Stanley Kubrick Think of Alan Conway’s Con?

But what of the real Kubrick in all this hubbub? Conway’s scam skated by on two factors: the unquestioning awe of star-struck acquaintances and the director’s lack of social presence. Although Kubrick shunned public attention, he was still alive and well, and surrounded by a professional network. According to Frewin, Kubrick was made aware of the whole Conway con when Warner Bros. were inundated with calls from supposed friends desperately trying to reach the director. They had been promised financial backing, roles in movies, and introductions to the right people, but now this famous auteur was ripping away opportunities that they had counted on with his silence. The real Stanley was reportedly baffled and amused by Conway’s chutzpah: “[he] could always see the humorous side of things: ‘I’ll get my own back on this guy. I’ll go around pretending I’m him!’” Frewin writes. Kubrick’s wife Christiane didn’t find it quite so funny. “It was an absolute nightmare. This strange doppelganger who was pretending to be Stanley. Can you imagine the horror?” she told The Guardian in 2005.

The truth was that Stanley Kubrick was safely tucked away at his estate in Hertfordshire, England, enjoying the privacy he so desired. This was quite the opposite of the Kubrick that Conway was presenting, who was constantly out on the town, socializing and swindling young gay men for attention and petty material gain, like rounds of drinks and packets of cigarettes. But in the course of doing so, he destroyed dreams, careers, bank accounts, reputations, and businesses. There were very real consequences of his deception, and victims were often too embarrassed to involve the law because, as Frewin puts it, “it was one thing being conned, but another to go into court and let the whole world know you had gone to bed with a man on the promise of a recording contract.”

Does ‘Color Me Kubrick’ Measure Up To The Real Story?

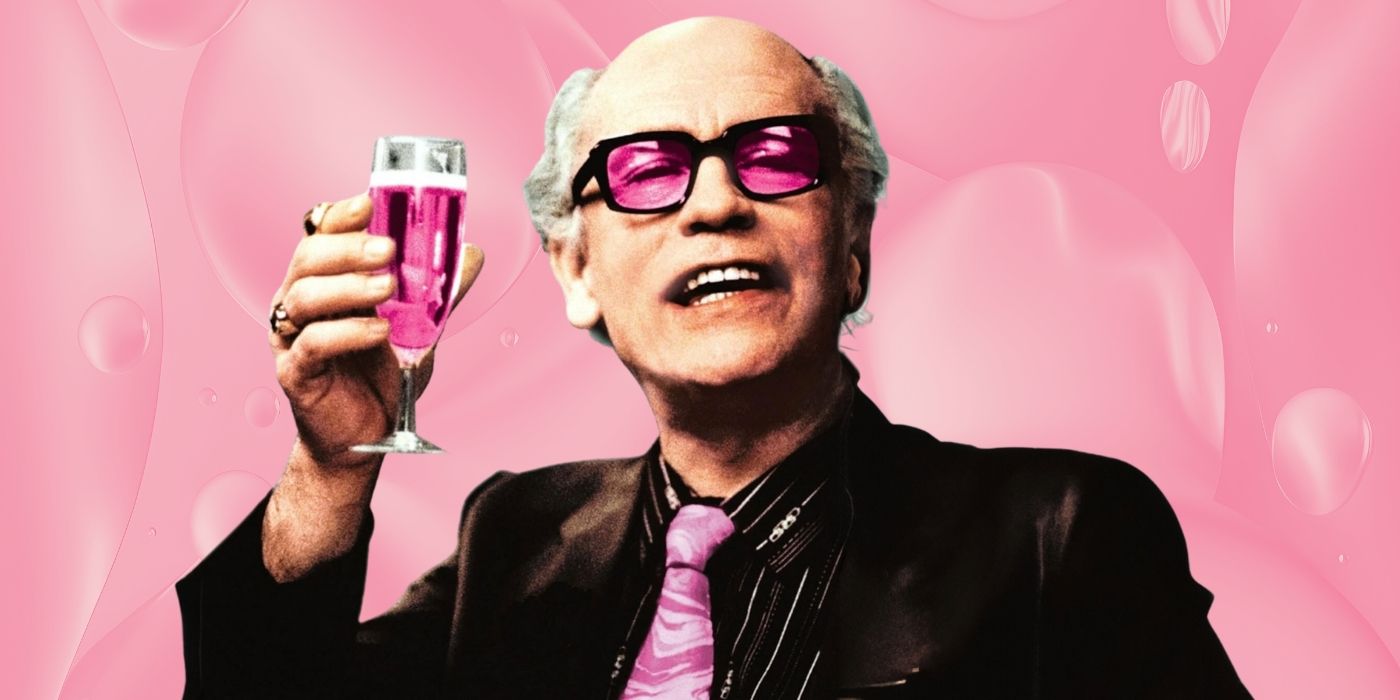

Color Me Kubrick was slowly released between 2006 and 2007, to a surprisingly minimal reception. One would think that such a premise would have been a bigger deal, as a wacky true story involving one of history’s most prominent directors. The mediocrity of Color Me Kubrick didn’t stop at its release and box office performance, however. The movie is a bit of a confused mess, and that is a shame, because in better hands it could have been great. It should have been a punchy, witty, fast-paced chase à la Catch Me If You Can, starting from the petty beginning of the impostor’s scheme and escalating, with pursuers catching on, until their capture is nail-bitingly inevitable.

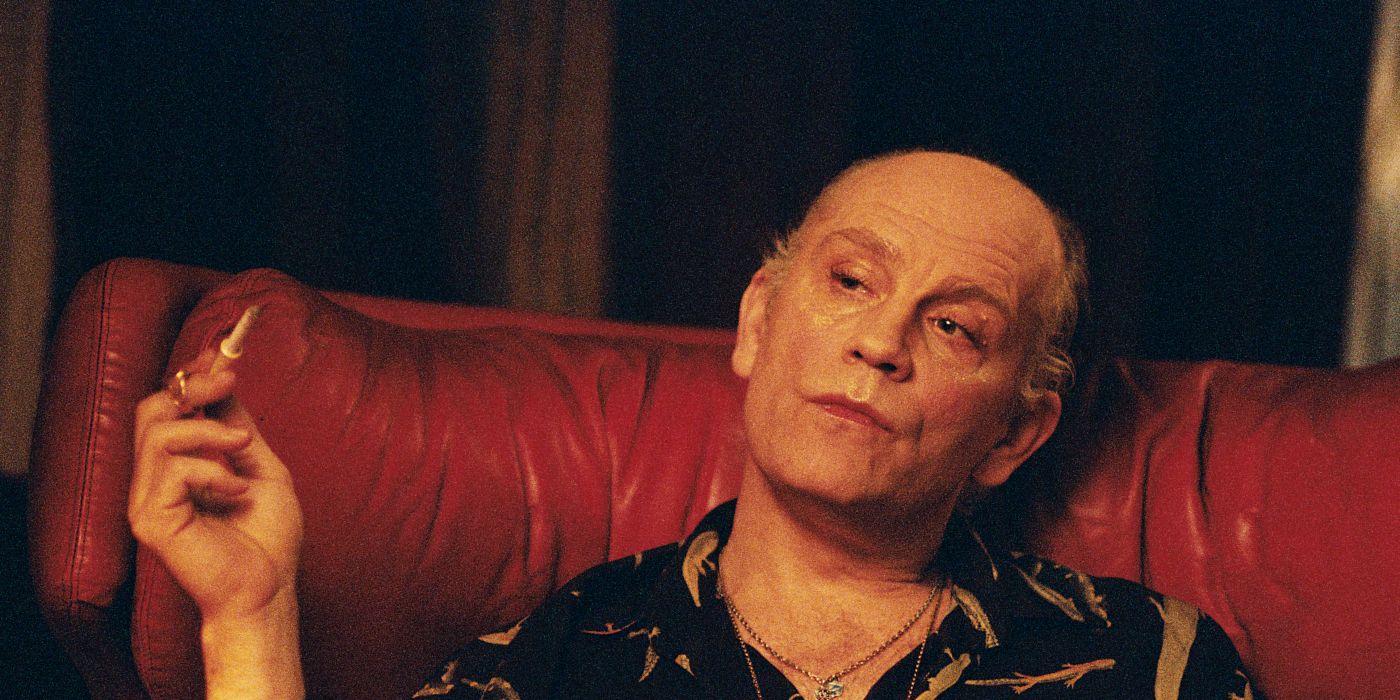

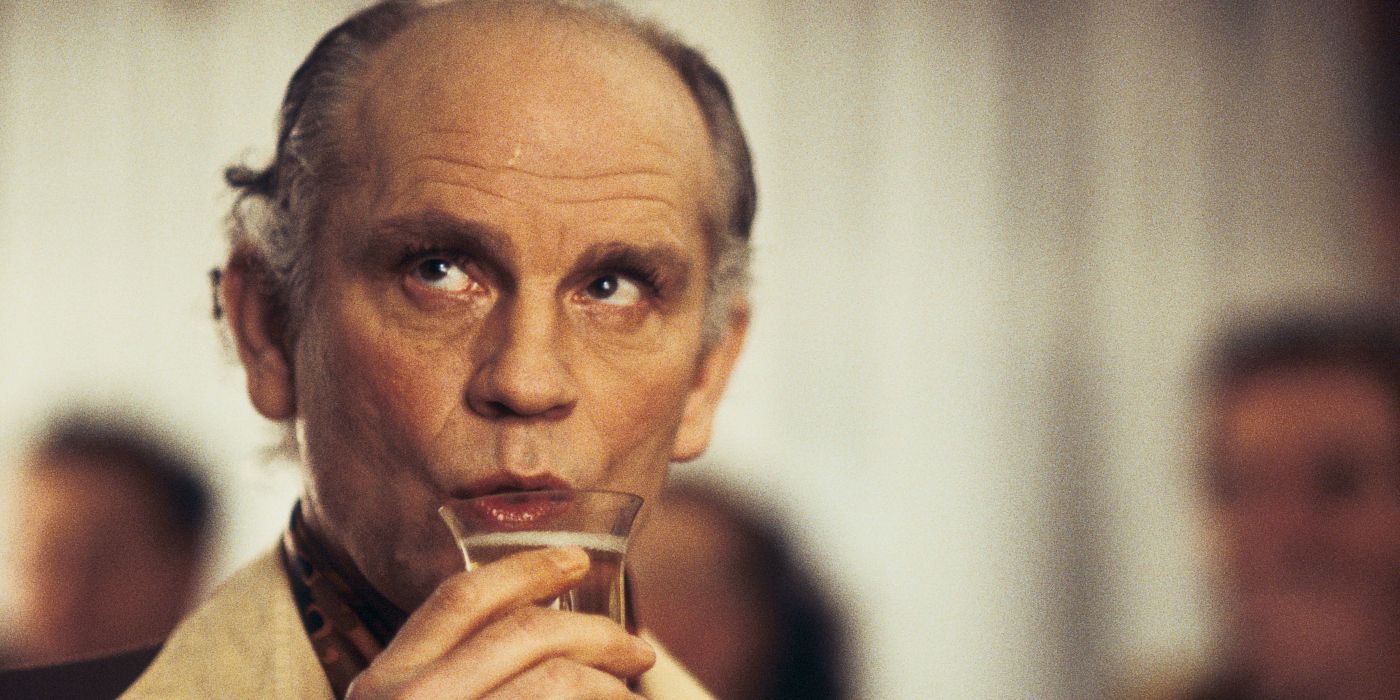

The last ten minutes or so of Color Me Kubrick works very well and ends on a decent note, it’s just that the bulk of the movie fails to live up to its potential. A key problem is a lack of progression or momentum. Until the finale, the action doesn’t really feel like it’s building to a spectacular fall. There is no sense of things starting small and snowballing — it’s just 75 minutes of Conway pulling a fast one on a variety of ambitious men and then moving on to the next. Malkovich gives an expectedly good performance as Conway. Just as it’s difficult for a good singer to pretend they can’t sing, it’s tough for an actor of Malkovich’s stature to play a bad actor, but he pulls it off as only he could.

‘Color Me Kubrick’s Theatrics Weren’t Suited For a Movie Screen

Conway flounces through the movie looking like a thrift store Peter Bogdanovich, purring men into a false sense of security all over London while pulling out a variety of crappy accents. It’s just as well the movie has the reliable Malkovich to fall back on, because the rest of the acting is… well, it leaves something to be desired. All the other actors are playing for the back rows, performing in a way that is much better suited for theater than for the screen. It is simply too dramatic to be believed as real people living real lives. To be fair, Frewin’s horrible dialogue does the actors no favors, nor does his stereotypical depiction of gay men, who are all colorfully-dressed and perched neatly on the edges of their seats in cocktail bars, gossiping about old Julie Christie movies in exaggeratedly posh accents that this Brit has never heard come out of a real person. In the theater, all of this could have worked, but it’s just too over-the-top to suit the screen, especially given that it steers well clear of any sense of camp that could have redeemed it.

What’s most striking about Color Me Kubrick is the feeling of unreality to it all. The production value is a fraction below what one would usually expect from a light British comedy, the writing and acting are just bad, and the use of music is so on-the-nose that it all feels a bit amateur. Iconic score pieces from Kubrick’s best-known movies are jarringly inserted all over the place, while a number of pop songs, such as Bryan Adams’ I’m Not The Man You Think I Am destroys any hope for a little subtlety. The whole production has the feeling of being made by student filmmakers whose naïveté convinces them they are making clever stylistic choices because they haven’t yet developed the nuance to recognize it all as far too obvious. It leaves one to wonder whether it’s just not a good movie, or if it’s a pretty sharp movie that is deliberately being lazy and basic as a reflection of Conway’s lazy and basic deceptions. I suspect the former, but if a better leader could have pulled it in a firmer direction and allowed the movie to pick a lane between flamboyant comedy and serious crime drama, it really could have been something.

So after all that, what is there to say of Alan Conway? Despite Malkovich’s strong performance and the odd glimpse into Conway’s thoughts and motives offered by a scene in which he throws himself around in feigned despair when one of his victims discovers the truth, Color Me Kubrick does little to explore him as a person. In truth, the two articles discussed here do a much better job of telling Conway’s story than the movie about him does. While Frewin is not an inexperienced or untalented writer, his idea would have worked better on the stage, or perhaps just as a straight journalistic book. Evidently, Frewin didn’t know much of Conway as a person, only of the crazy things he did. It’s still a great story, one that has to be seen to be believed, and perhaps one day, someone better equipped will have another go at telling it on the screen. But until then, through all the outrage, heartache ,and criminality that defined Conway’s life, his son boiled it down to this: “He was a compulsive liar.”