In the vast history of Hollywood and the filmmaking medium as a whole, there is no career quite as illustrious and seismic as Clint Eastwood’s. The actor-director has been a mainstay in cinema for roughly seven decades. Before the SAG-AFTRA strike, he was in production for what is believed to be his final film, Juror No.2, at the miraculous age of 93. Eastwood never stops working and has an impressive filmography to back it up, starring in a number of monumental and impactful films including Unforgiven, Dirty Harry, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. From a broad perspective, Eastwood will always be lauded for his portrayal of cops and cowboys on the big screen. However, over the last decade, the masculine icon has quietly become the go-to auteur for adapting true stories and the lives of complex real-life heroes onto film. What this phenomenon says about the individual is ambiguous, but for someone as reflective and meditative of his image as Eastwood, there has to be something of tact.

Clint Eastwood’s Recent True Stories Include ‘Sully,’ ‘American Sniper,’ and ‘Richard Jewell’

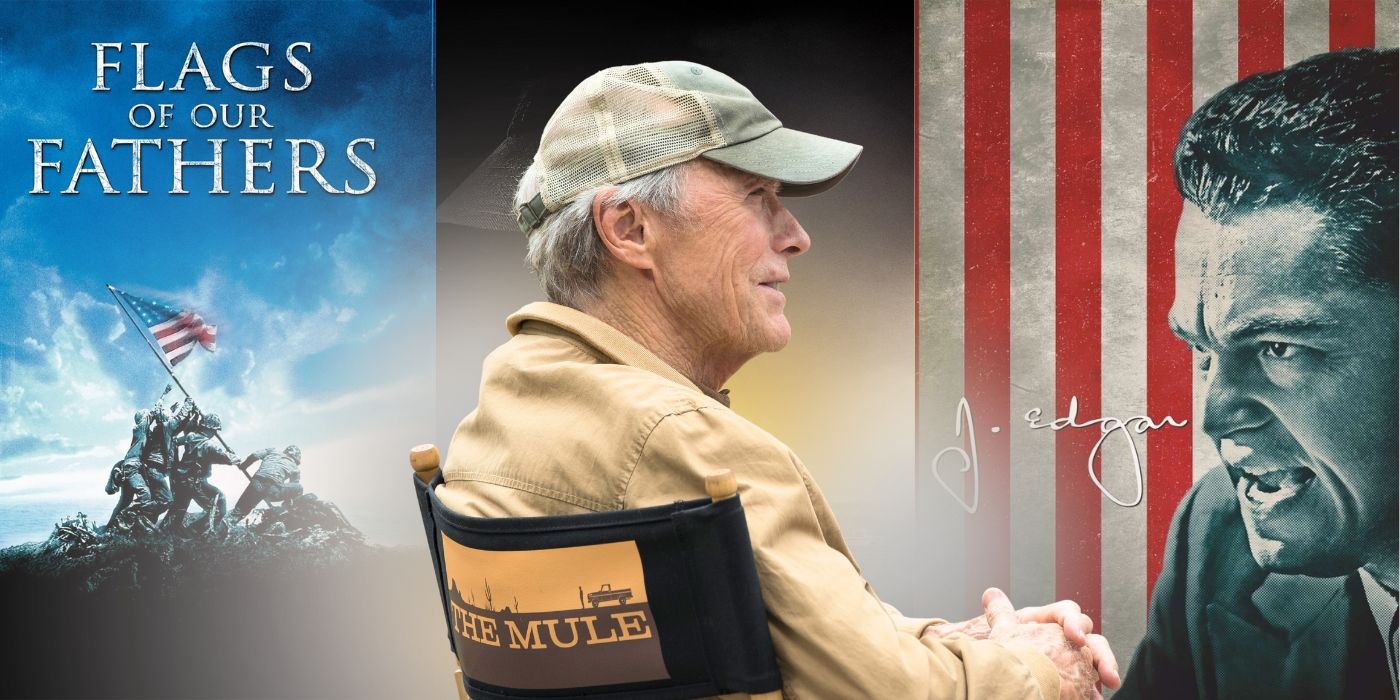

Following Million Dollar Baby, which earned Eastwood his second Academy Award for Best Director and Best Picture in 2005, Eastwood could now do no wrong. He became a great athlete who had won at the highest level of competition on multiple occasions. Having proven everything as an actor, director, and icon of the medium, Eastwood was ostensibly playing with house money. From this point forward, the majority of Eastwood’s films (working almost exclusively behind the camera) are based on real events and figures, starting with his dual Battle of Iwo Jima companion films: Flags of Our Fathers, and Letters from Iwo Jima. Soon enough, Eastwood’s comfort zone was in the form of the biopic, collaborating with big-name actors to portray significant political, cultural, and sociological figures, such as Nelson Mandela, J. Edgar Hoover, The Four Seasons, Chris Kyle, Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, and Richard Jewell.

Many of these films, including American Sniper, Sully, The Mule, and The 15:17 to Paris, depict events from the 21st century, with the latter, the story of three Americans thwarting a terrorist attack on a train, only occurring three years before the film’s release. A fundamental throughline in these true-to-life adaptations is the portrayal of heroes in impossible situations, and how the subsequent external fanfare weighs upon their psyche. His dedication to telling the stories of real courageous figures reached its apex when he rolled the dice by casting the real subjects of The 15:17 to Paris, Spencer Stone, Alex Skarlatos, and Anthony Sadler, to play themselves on screen, creating a fascinating blend of narrative and documentary filmmaking with mixed results.

Eastwood’s unofficial series of films also feature the element of the “empty suit” pencil-pusher, usually belonging to the government or media, who is determined to undermine the subject’s heroism, as seen with the National Transportation Safety Board’s skepticism of Sully Sullenberger’s (Tom Hanks) tactics in his emergency landing on the Hudson River, or the FBI and mainstream media’s defamation of the titular Richard Jewell (Paul Walter Hauser), who is initially celebrated as a hero for alerting authorities of a bomb at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. This dynamic triggers inherently rich drama, but this character device has also been somewhat of his Achilles’ heel over the last decade. This thematic trait has landed Eastwood in controversy, with his skewed depiction of the NTSB in Sully and media in Richard Jewell, with the latter centered on journalist Kathy Scruggs (Olivia Wilde), who is broadly characterized with the nefariousness of a Bond villain.

Why Does Clint Eastwood Prefer To Direct Movies Based on True Stories?

To accurately identify why Eastwood has carved out a filmmaking niche for himself in the field of adapting true stories, it’s advantageous to look at the primary source himself. During the press tour for Richard Jewell, Eastwood sat down with CinemaBlend and was asked about his recent preference towards films directly based on real-life events and people. “There’s no particular formula,” the director responded. He stated that scripts based on true stories spontaneously end up on his radar. Eastwood’s seemingly indecisive answer does not subscribe to any notions of auteurism or metatextual qualities. His unfussy approach to selecting projects parallels his unpretentious and expeditious manner of directing, which famously involves the director shooting merely one take for a respective scene, or using a fake baby in American Sniper. At this point in Eastwood’s life, it is more efficient to tell stories from a slice of life and recent American history.

Despite his humility in this interview, few stars or artists are quite as reflective and meditative about their public persona as Clint Eastwood. Arguably his magnum opus, his other Best Picture winner, Unforgiven, deconstructs the nobility of the Western vigilante and the devilish implications of violence and upholding “justice.” The film boldly asserts that the Eastwood screen image that audiences grew to love, even as the fascist-minded law-pushing police inspector, “Dirty” Harry Callahan, was a reprehensible figure. Before Unforgiven, the star specialized in revisionist Westerns that demystified cowboys and outlaws, particularly High Plains Drifter and The Outlaw Josey Wales. Underrated gems of his like A Perfect World unravel the broken souls of men on both sides of the law. From Unforgiven through Gran Torino, Eastwood reckoned with how his older years of age affect his image and outlook on the world. These films are barred by a fleeting grasp on the ways of life in the 21st century. Artistic trends are omnipresent in Eastwood’s filmography. This recent trend of stories ripped from headlines and autobiographies on the big screen can’t be any accident.

Clint Eastwood’s ‘Sully’ and ‘Richard Jewell’ Boost Unlikely Heroes

The aforementioned character takedowns that exist in Eastwood’s recent films from government and media figures show that the truth is precarious, and it is written by those who control the narrative. Eastwood, who understands Westerns and its associative mythmaking as well as any living artist, interprets the truth as an invaluable virtue. This is not to say that American Sniper and Richard Jewell are the definitive accounts of their subjects’ lives. However, the sincere treatment of these real-life protagonists assigns proper heroism to the likes of Kyle, Sullenberger, and Jewell from a Hollywood legend who was cemented by the public as an American icon through fiction.

It has become a habit among film scholars and critics to interpret Clint Eastwood’s films through the lens of his politics and personal beliefs. As a result, it’s easy to chalk up the director’s run of films based upon real-life heroes as a simplistic worldview or, in certain instances, blatant jingoism. This would discredit Eastwood’s nuanced portrayal of his subjects as complex individuals, whose moral compass and acts of heroism can be scrutinized. Through their courage and flaws, these characters, with the aid of stellar performances from Morgan Freeman, Bradley Cooper, Tom Hanks, and Paul Walter Hauser, are expanded as human beings. Audience reactions to their performances are intended to be ambiguous. These celebrated heroes can be selfish, cold, and unknowable. Some viewers may be incredulous towards the valiant actions of his characters, while others are enchanted by their heroism. For Clint Eastwood, a director with a tempered voice, this dichotomy is the ideal characterization of real-life figures and their true stories.