Horror films are something you have to prepare for. Whether it’s gripping the seat or shielding your eyes or ears, or wrapping yourself up in a world full of tension and menace, great horror movies are much more than jump scares. Utilizing the sound of floorboards, the movement of shadows, the unpredictability of mist, horrific or hilarious (or hilariously horrific) deaths, or a tingling film score—this genre is always playing with the audience. The greatest horror films can be heady and philosophical, slapstick or serious—in short, if you’re a fan of horror, most likely you’re a fan of cinema. No other genre best represents how the moving image can affect us—by using every filmmaking tool in the shed.

Horror cinema has seen historic highs; the best horror movies never really leave your mind for good. But which of the genre’s finest are the very, very best? Below are the greatest, the most unforgettable—and indeed the most frightening—horror movies ever made, ranked from great to greatest.

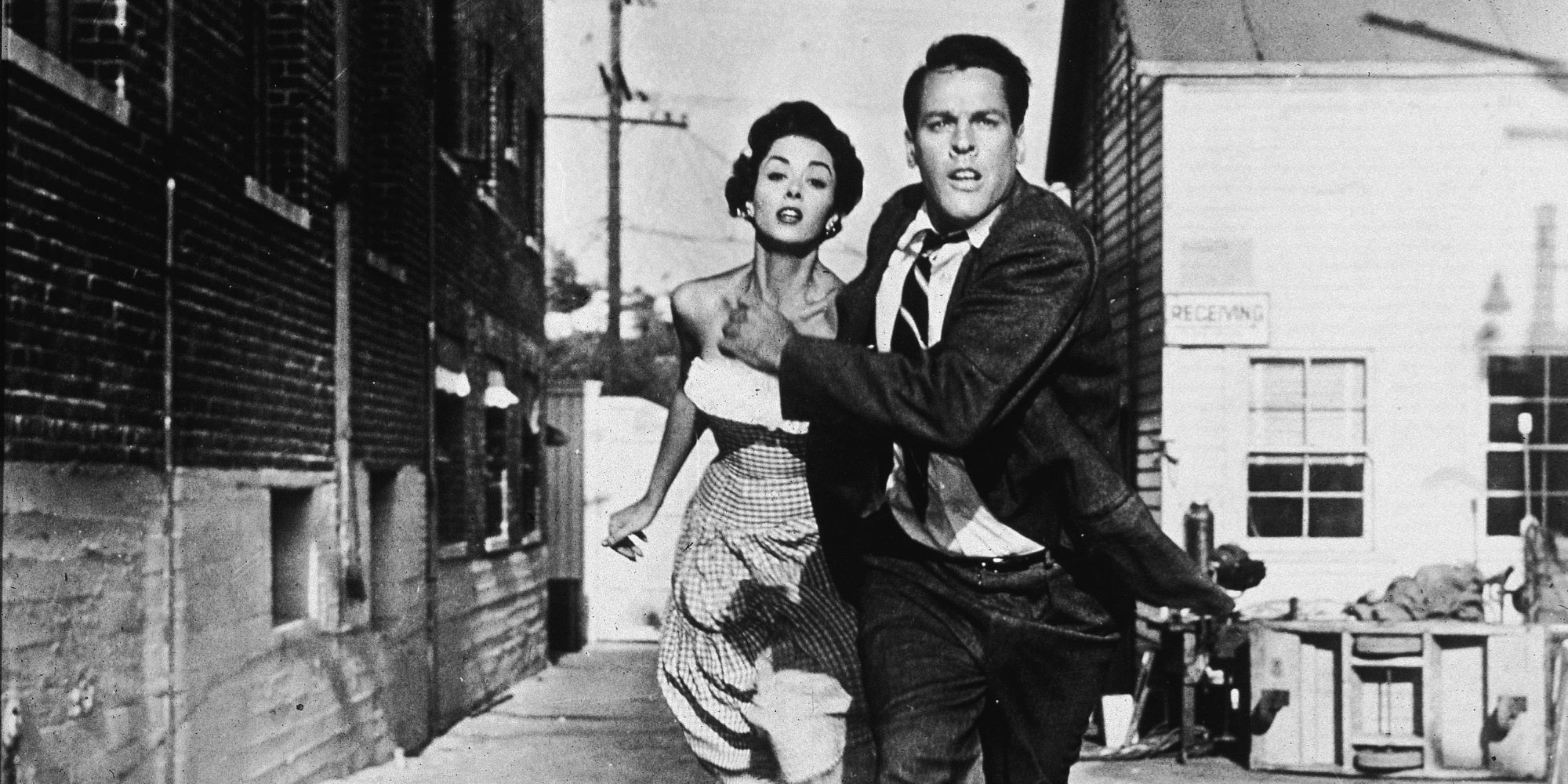

25 ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ (1956)

When Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) begins to hear the same story from all his patients, that their loved ones are acting strange, he investigates the matter. He discovers that the cause is otherworldly: aliens have discreetly invaded Earth and are replacing humanity, growing their own duplicates from plant-like pods.

While there have been numerous adaptations of the legendary science-fiction novel, the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers remains the best. Often the creatures in horror movies take on the form of a horrific beast, but as Invasion of the Body Snatchers shows, facing a villain that can take the shape of your closest friends and family is just as terrifying, if not more so.

24 ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ (1920)

Director Robert Wiene‘s tale about a traveling showman and his fortune-telling somnambulist (a.k.a. sleepwalker) is a haunting example of the absurd angles and exploration of madness that’s at the heart of German Expressionism, but it’s also an outgrowth of the fears and experiences brought about by World War I.

Screenwriters Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz brought their pacifist and anti-authoritarian message to the script, a message the rings loud and clear throughout the picture. However, the bookends of the film’s framing story serve to undercut that message rather than underscoring it. This interpretation may be a subject of debate still, but its place in horror history is rock-solid thanks to Cesare the Somnambulist and the beastly, duplicitous Dr. Caligari. — Dave Trumbore

23 ‘Get Out’ (2017)

Meeting your in-laws for the first time can be a nerve-wracking experience for anyone, but Get Out takes that relatable dilemma to scary new places. When Chris (Daniel Kaluuya’s Oscar-nominated, star-making performance), a young Black man, travels with his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams) to meet her family, he discovers their seemingly perfect life harbors dark secrets.

A breakout horror hit and the debut of modern horror master Jordan Peele, Get Out won countless fans thanks to its gripping story packed with social commentary and genuine scares. One of the best and most influential horror movies so far this century, Get Out’s screenplay won Peele an Academy Award and announced him as one of the brightest stars in the genre. — Ty Weinert

22 ‘Scream’ (1996)

Wes Craven’s masterwork shares some DNA strands with Alejandro Amenabar’s Thesis from 1994, but whereas Amenabar leaned heavier on the academic tone, Craven indulges with colorful, anxious imagery that has denoted his pulpiest gore-laden delights, from A Nightmare on Elm Street to The Serpent and the Rainbow. The story itself, however, similarly toys with the moralism of enjoying horror movies, with Jamie Kennedy representing the giddy, know-it-all fanboy contingency and Skeet Ulrich representing the over-it seducer with Neve Campbell’s sanctified Sidney Prescott stuck in the middle as her friends and classmates are carved up by the now-famous Ghosface killer.

Sure, there’s a minor kick in watching these stereotypes get sliced and diced, but Craven’s post-modern conception here brings unfussy maturity to a genre that was always denoted for its general cheapness and impersonal feel. Scream marks perhaps the most personal and reflective of all the slashers, and represents a major turn towards big-budget horror as a place for burgeoning auteurs to hone their craft and flourish in distinct new directions. — Chris Cabin

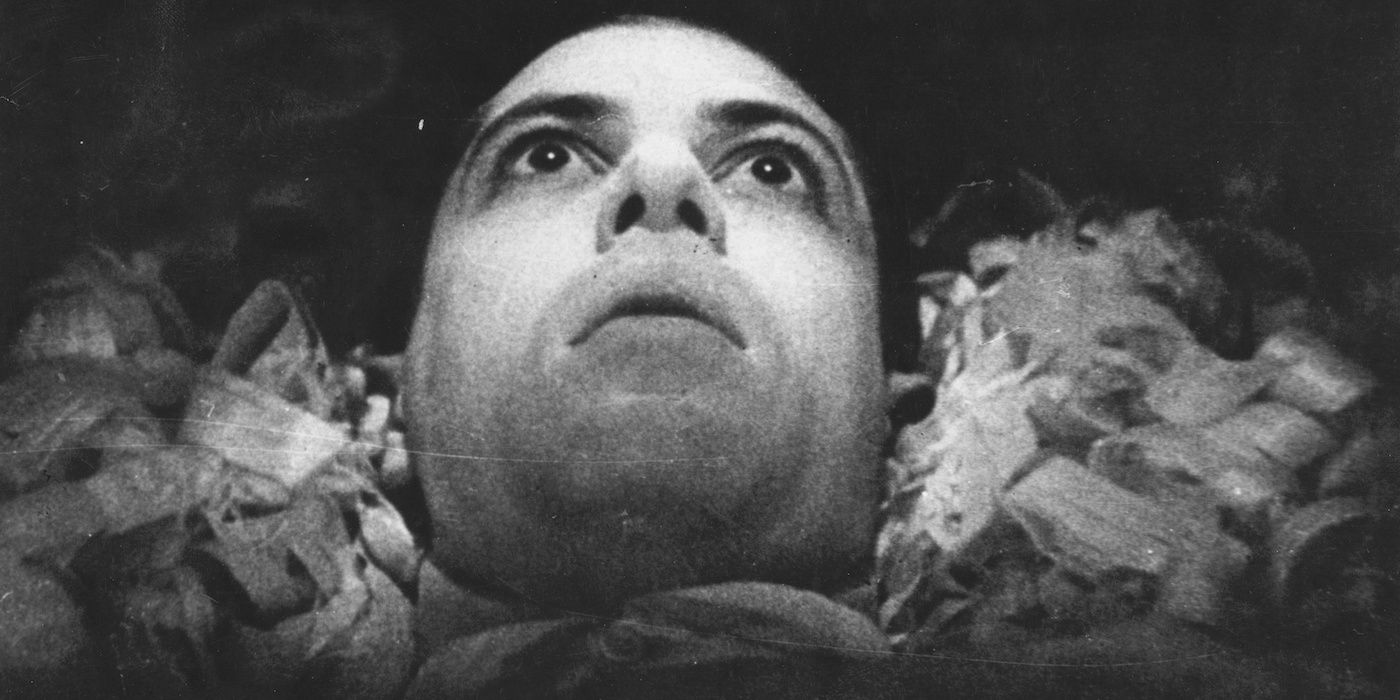

21 ‘Vampyr’ (1932)

Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer is behind the seminal 1932 horror film Vampyr. Nicolas de Gunzburg —under the name Julian West —stars as Allan Gray, a young student fascinated by the occult. Stumbling upon a French village, Allan becomes involved with an older man and his sick daughter, who’s slowly succumbing to the curse of vampirism.

Enhanced by its immersive black-and-white cinematography, Vampyr is an oneiric, unforgettable picture and a triumph of 1930s horror. Although hard to follow and lacking structure, Vampyr is a visual feast, offering disturbing and elevated visuals that will satisfy loyal horror viewers – and haunt the dreams of anyone brave enough to watch it. — David Caballero

20 ‘Hereditary’ (2018)

Mourning the loss of her estranged mother, Annie (Toni Collette) and her family attempt to put their grief behind them as they move on with their lives. But when strange and terrifying events begin plaguing each family member, they find themselves caught in a darkness that threatens to rip them apart forever. The external threats of Hereditary are scary enough, but the more profoundly disturbing content here is the tragic unraveling of a family, bolstered by some of the finest performances in the genre’s history (most notably Collette, lamentably snubbed for an Oscar nod).

While Hereditary feels more like a dark drama than a straight horror movie at times, it features one of the most haunting atmospheres in the genre. Even when there are seemingly no threats on screen, first-time feature director Ari Aster still manages to keep the audience feeling unsettled, creating a film that sticks with you long, long after the credits have rolled. — Ty Weinert

19 ‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ (1984)

With A Nightmare on Elm Street, Wes Craven introduced one of horror’s all-time greatest villains in Robert Englund‘s Freddy Krueger, a cruel and crass killer of children who somehow manages to charm even as he cuts his way through the innocents of Elm Street. In fact, Krueger’s legacy has grown so great over the years, spawning seven sequels and a remake along the way, that it can outshine how incredibly innovative and well-executed Craven’s original film was, and how inherently brilliant the film’s basic idea was.

Craven took the slasher concept popularized by films like Halloween and Friday the 13th, twisted it through the lens of nightmarish dream logic,and redefined it through subtle genre deconstruction (though nowhere near as outright as his New Nightmare and Scream). Craven found a way to take the tropes of the slasher genre and reshape into the legend of Freddy Krueger. You can’t escape most slasher killers because, well that’s just how the genre works, but it’s innate to Krueger’s very construct. — Haleigh Foutch

18 ‘Frankenstein’ (1931)

Boris Karloff burst onto the scene in a big way as the Monster in James Whale’s this briskly paced mad-scientist thriller that’s arguably even more influential than Dracula (released the same year). Thanks to Carl Laemmle Jr.’s foresight in landing the rights to Dracula and that film’s nearly instantaneous success, Universal Pictures greenlit a number of monster pictures, of which Frankenstein would be next. It also features a curious introduction by actor Edward Van Sloan who warns the audience that the story of Frankenstein might horrify us, which of course only added to the titillation.

Despite its relatively short runtime of 70 minutes and its prevalence in our modern culture, Frankenstein was heavily censored in certain regions upon release. One scene that was long considered controversial–and is probably my favorite part of the whole picture–is when the monster throws a little girl into the lake, ultimately drowning her. Other censors asked to cut Dr. Frankenstein’s line about knowing what it’s like to “be God”, the same line in which he famously shouts, “It’s alive!” Fortunately, the original cut has survived to this day. — Dave Trumbore

17 ‘Night of the Living Dead’ (1968)

The zombies in George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead are called “ghouls” but nonetheless this is the film that created the movie zombie as we know them: blank, thoughtless creatures who lumber around with vacant stares and barely retain any resembling sense of their humanity. For this reason, the thrill of the movie zombie has generally been in seeing how our heroes with brains dispatch them with great efficiency and cruelty. They’re no longer human, after all.

However, re-watch Romero’s film and try not to escape with having more sympathy for the “ghouls” than most of the humans. The living humans mostly only retain humanity’s weakest learned attributes: prejudice, xenophobia and selfishness. The most selfless non-ghoul we follow (Duane Jones) is famously shot—after valiantly fighting against the ghouls—simply because his skin color triggers a suspicious reaction to the man on the other end of the rifle. —Brian Formo

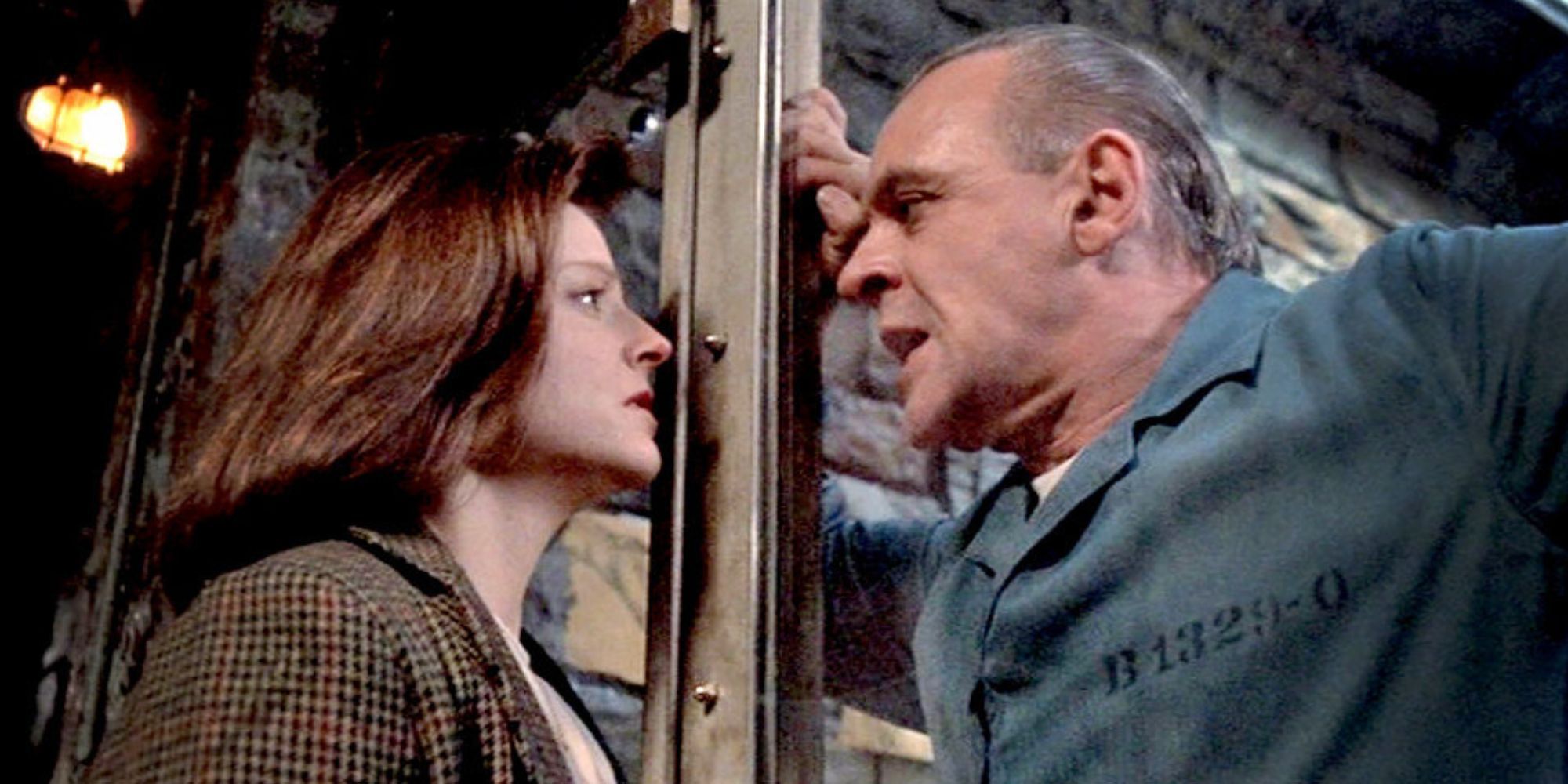

16 ‘The Silence of the Lambs’ (1991)

The late Jonathan Demme directed Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins to Oscar wins with his powerful 1991 horror thriller The Silence of the Lambs. Based on Thomas Harris’ eponymous novel, the plot follows Clarice Starling, a young FBI trainee tracking Buffalo Bill, a serial killer targeting women. Hoping to gain new insights into Bill’s mind, she arranges a meeting with the notorious cannibalistic killer Hannibal Lecter, forming a complex relationship with him.

To this day, The Silence of the Lambs remains the only horror film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards – and only the third to win the Big Five Oscars. A stunning and riveting thriller that effortlessly goes from heavy drama to petrifying suspense, The Silence of the Lambsis a gem of modern horror, a psychological and emotional nightmare that creeps deep within the viewer’s skin. — David Caballero

15 ‘The Thing’ (1982)

If you’re making a case for remakes that vastly improved upon the original work, look no further than The Thing. Adapted from John W. Campbell’s novella “Who Goes There?”, which was previously adapted by Howard Hawks and Christian Nyby as The Thing from Another World in 1951, the 80s version remains the preferred and iconic version of the story today.

And how could it not? It featured Carpenter in his prime, riding high with Russell from their experience on Escape from New York the year before; the amazing practical creature effects were churned out by Oscar-winner Rob Bottin with an assist from the legendary Stan Winston; Tobe Hooper worked on a draft of the script; and the one-and-only Ennio Morricone composed the score. The story follows a tough crew of researchers at an Antarctic station who come into contact with a dangerous alien shape-shifter. From the completely insane opening sequence, to the unabashed reveal of an extraterrestrial spaceship, to the cat-and-mouse game played between the entity and each of the surviving humans, The Thing could arguably be called the best sci-fi horror film of the ’80s. – Dave Trumbore

14 ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ (1968)

Mia Farrow plays one of her most iconic roles in the 1968 psychological horror film Rosemary’s Baby. The plot centers on Rosemary Woodhouse, a young woman who becomes pregnant and begins to suspect her neighbors are grooming her to use her baby in satanic rituals. The film co-stars John Cassavetes, Sidney Blackmer, and Ruth Gordon in the role that won her the Best Supporting Actress Oscar.

A masterclass in tension and claustrophobic horror, Rosemary’s Baby is a thought-provoking horror movie widely regarded as a classic. Exploring themes of maternity, frustration, paranoia, and religion, the film is a dark take on the 1960s sexual revolution. Rosemary’s Baby crafts a seamless and chilling marriage between its director’s famous idiosyncrasies and the very real, raw horror of living in a society that punishes those who speak up. — David Caballero

13 ‘Dawn of the Dead’ (1978)

Dawn of the Dead may well be the greatest zombie movie of all time. For his sequel, Romero dodged the temptation to retread familiar territory (a quality he would maintain for each of his subsequent “of the dead” films, even as they become a series of diminishing returns), ditching the intimate confines of a home for the sprawling (but still confined) reaches of a shopping mall, and trading his black-and-white bleakness for a playful color-saturated palette.

Dawn of the Dead is a horror sequel in every sense, bigger and bloodier, but it maintains Romero’s commitment to skewering social commentary, this time tackling American consumerism. It’s also packed to the brim with Romero’s skilled eye for visceral violence rendered with first-rate old-school gore effects from Tom Savini, the legendary craftsman of carnage who transplanted his experience as a combat photographer in Vietnam to a career spent creating on-screen nightmares for generations. —Haleigh Foutch

12 ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’ (1974)

Tobe Hooper‘s sophomore feature film is a brilliantly blunt deconstruction of human mortality that forces us to confront the reality that we are all but meat and bone racing toward the unavoidable moment when we cease to be anything but a decomposing corpse. It’s brutal and basic, and that ruthless efficiency is what makes it such a grueling, unnerving watch to this day. What’s more, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre revels in the reality that death does not have sympathy, it does not care who you are — strapping and strong, young and beautiful, good-natured, kind, weak, meek, abled or disabled —death comes for us all.

The setup is simple, and it’s all in the title, a group of good kids make a detour in Texas where they are massacred one by one, sometimes with a chainsaw. It’s a genre-defining entry in backwoods horror, a relentless onslaught of butchery that invokes sledgehammers and meat hooks and, of course, chainsaws as implements of horrific violence and depravity. It’s almost too ugly and too effective to ever be really “enjoyed”, a bit like staring in the face of the worst-case-scenario underlying humanity’s inherent mortal fears, but it is an undeniable achievement of the horror genre that achieves something like timelessness.— Haleigh Foutch

11 ‘Nosferatu’ (1922)

In one of the earliest of vampire films and still, to this day, one of the absolute best, F.W. Murnau does not attempt to romanticize his vampire but instead presents him as a diseased and weaselly shell. Count Orlok (Max Schreck) is the physical representation of death. With pointy ears and nose, structurally, he has the face of scavenger, and the long pale claws of a devil. Murnau does not attempt to film Schreck in a manner that would imply that he used to be human; with his claws and hunched posture, his every movement appears as though he’s dragging hell within his shadow. Yeah, not romantic.

Despite all warnings from the town, an agent and his bride travel to visit Nosferatu, who hopes to purchase a new estate. There is a big payday if the agent completes the sale, but his bride is also at stake. And while future films will go to great and exciting lengths to romanticize and sexualize the creature that beckons a potential eternal bride, Nosferatuworks as a stunning metaphor for the blindness people have when financial rewards are dangled. Even when it’s dangling from claws. —Brian Formo

10 ‘Peeping Tom’ (1960)

Audiences were so horrified by Peeping Tom that it was actually pulled from theaters. They felt violated and betrayed because one of the most revered and hopeful of Britain’s directors, Michael Powell (The Red Shoes), had made something perverse and psychotic. He made viewers confront the level of thrill-seeking they hope to get from a moving image by following a smutty photographer/amateur filmmaker (Karlheinz Böhm) who photographs erotic pics for side money, but gets his real thrills from filming women while he stabs them to death with a blade on his tripod.

When the photographer begins to form a friendship with his downstairs neighbor, he attempts to reform, but his psychosis goes much deeper than thrills and reveals a nefarious experimentation in fear, with his father as the controller and he as the subject. Powell, who always possessed one of the most impressive filmmaking eyes, uses the grainy mouth-open screams of women to communicate to the audience that the act of filmmaking is providing something to voyeurs. — Brian Formo

9 ‘Let the Right One In’ (2008)

Thomas Alfredson‘s 2008 masterpiece is an adolescent vampire film only in the most literal sense. Adapted from the novel of the same name by John Ajvide Lindqvist (who also penned the screenplay), Let the Right One In is a staggeringly mature and intellectual spin on immortality, bloodlust, and the need to belong told through the contrast between first love and ancient longing. The story focuses on an outcast and disturbed 12-year-old boy Oskar, who bonds with his new neighbor, Eli, an enchanting immortal in a child’s body with an unquenchable thirst for human blood. As the oddball duo earnestly connects over their shared macabre obsessions and deepest secrets.

Let the Right One In is an absolutely gorgeous film that showcases remarkable work from cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, but its deeper beauty lies in the tender and terrible emotions it evokes, vacillating between the heart-warming and horrific with a rich, soulful sadness. A vampire film unlike any before it, Let the Right One In is one of those rare cinematic blessings that pushes the boundaries of genre and escalates it to new heights. — Haleigh Foutch

8 ‘Jaws’ (1975)

Jaws is arguably the first modern blockbuster and a before-and-after in commercial filmmaking. It’s also a superb horror picture and one of Steven Spielberg’s greatest achievements. The plot centers on the joint efforts of a marine biologist, a police chief, and a shark hunter to stop a great white shark from terrorizing a summer vacation resort.

A near-perfect thriller, Jaws is a game-changing victory that revolutionized horror. The film emphasized atmospheric rather than overt thrills – the shark doesn’t show up until after the one-hour mark and has less than five minutes of total screen time. Yet, its presence looms large, casting a dreadful shadow that envelops the plot and, by extension, the audience. Jaws is a masterpiece, featuring one of John Williams’ most iconic scores and presenting Spielberg in full visual and narrative command of his craft. — David Caballero

7 ‘Bride of Frankenstein’ (1935)

Picking up after the events of the first film, James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein sees Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) trying to distance himself from his creation as it continues to wreak havoc. Instead, Frankenstein finds himself forced by his former mentor to create a bride for the monster.

While the original Frankenstein is a classic, Bride of Frankenstein is the superior film. Its campy tone and timeless performances mean it holds up just as well today, while its influence is still felt as it is frequently parodied or referenced in a range of other media. The most iconic and celebrated parody is, hands-down, Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein, undeniably the best spoof movie ever made.—Ty Weinert

6 ‘Kwaidan’ (1964)

An anthology film, the four stories featured in Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan are based on Japanese folk tales. Each features elements of the supernatural, with one following a poor samurai as he leaves his wife for a wealthy woman only to suffer a tragic fate, while another sees a blind musician performing for an audience of ghosts. Kobayashi stepped into the horror genre with Kwaidan between the releases of his all-time samurai classics Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion.

Despite being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, Kwaidan remains quite underrated outside of hardcore horror circles. Absolutely gorgeous, Kwaidan is one of the most beautiful horror movies of all time—frankly, it’s one of the best-looking movies from any genre—courtesy of its unforgettable set design. —Ty Weinert

.jpg)