The Big Picture

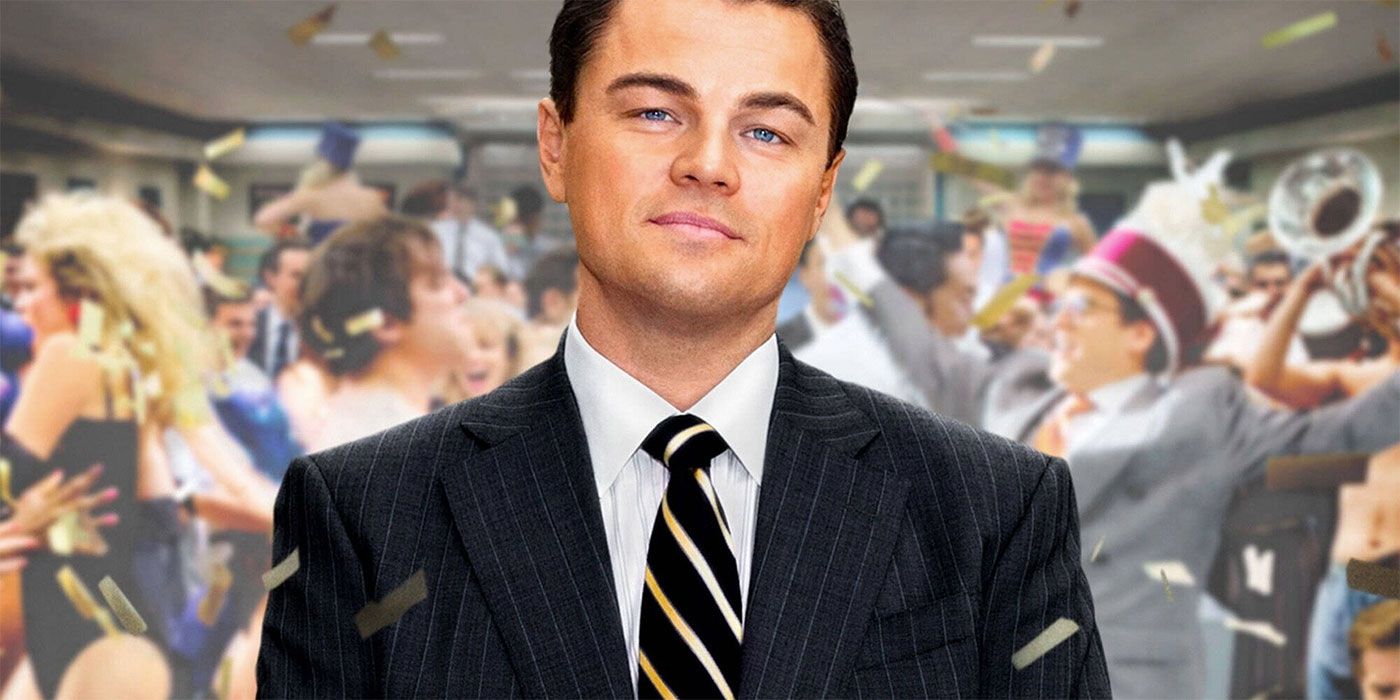

Martin Scorsese is no stranger to controversy. The violence in his crime films Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, Casino, and The Irishman certainly offended sensitive viewers, and Scorsese’s 1988 religious drama The Last Temptation Of Christ even inspired mass riots on behalf of extreme religious communities that took issue with the film’s depiction of Jesus of Nazareth. Recently, Scorsese’s comments have drawn the ire of an even more passionate group: comic book fans. His thoughts on the fate of the superhero genre and “content” in the modern industry have drawn some sharp responses from internet trolls. Along with these, one of the most divisive of Scorsese’s works is 2013’s The Wolf of Wall Street. Although some skeptics may claim that Scorsese used his 3-hour biopic to lionize the real crook Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio), the film’s brilliant ending shows the satirical point that Scorsese is evidently making.

What Happened to Jordan Belfort in ‘The Wolf of Wall Street?’

The Wolf of Wall Street is based on the real Jordan Belfort’s autobiography of the same name. As detailed in both the novel and film, Jordan is an ambitious Wall Street stockbroker who learns the art of money-making from his eccentric mentor Mark Hanna (Matthew McConaughey). Although Belfort loses his job during the “Black Monday” market crash in 1987, he discovers that he has the ability to convince potential investors to buy almost any product, even those that he knows aren’t valuable. As the film continues, Belfort and his wacky business partner Donny Azoff (Jonah Hill), who is based on the real Donny Porush, start a new business that they use to reward themselves with generous financial benefits. As Jordan’s New York firm grows richer and attracts more followers, his financial crimes begin to spark the interest of FBI Agent Patrick Denham (Kyle Chandler).

Belfort is desperate to get his money out of the United States in order to avoid the suspicions of the FBI’s federal crime units. Although Jordan initially relies upon his friend Brad Bodnick (Jon Bernthal) to take ridiculous amounts of cash to Switzerland, Brad ends up wearing a wiretap and exposing Jordan’s crimes to Denham. Jordan’s allies begin to turn on him; the FBI gets additional information on both his business partner Jean Jacques Saurel (Jean Dujardin) and Naomi Lapaglia (Margot Robbie), who is based on the real Naomi Macaluso. Jordan attempts to warn Donny about the pending investigation before he’s thrown in jail, and his firm Stratton Oakmont is shut down.

Despite the evidence stacked against him, Belfort is able to elude paying any real consequences. He’s sentenced to 36 months in federal prison, but the film’s version of a “maximum security” jail looks a lot closer to a country club than an actual confinement facility. Belfort is released from custody after serving 22 months. After his release, Belfort is even able to rebound and find another job in the financial world; he now hosts seminars on sales techniques. It’s during this final sequence that the real Belfort has a cameo as the seminar host who introduces DiCaprio’s version of the character to a crowd of potential investors.

‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ Satirizes Privilege and Charisma

It’s somewhat ironic that Scorsese faced the same criticism for The Wolf of Wall Street that he did for Goodfellas in 1990. With both films, some critics seemed to misinterpret depiction with endorsement. Scorsese shows in Goodfellas how violent, scary, and miserable the mafia life really is for men like Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) when they’re forced to inform on their former allies. In The Wolf of Wall Street, the emptiness of Jordan’s existence is revealed; his friends and family are keen to inform on him in order to avoid having to spend any time in jail themselves. Jordan may have grown a community of followers, but that doesn’t mean that any of them would go out of their way to protect him.

Nonetheless, it really never mattered, because the American justice system is systematically rigged in Jordan’s behavior. He is granted so much white privilege that “jail time” doesn’t affect his life at all, and even allows him to grow some notoriety as he goes back to the financial world. Scorsese shows how all-consuming the power of wealth is during the final sequence; while Belfort is playing golf and relaxing while he’s in jail, Denham is forced to take the subway to work at his miserable job. It’s amusing that Scorsese uses the song “Mrs. Robinson,” a song best known for its use in Mike Nichols’ classic comedy The Graduate. In the same way that The Graduate dispels myths about maturity and romance, The Wolf of Wall Street shows how ineffective the justice system is in the United States. It’s a system rigged in favor of men like Belfort.

Martin Scorsese Makes the Audience Implicit

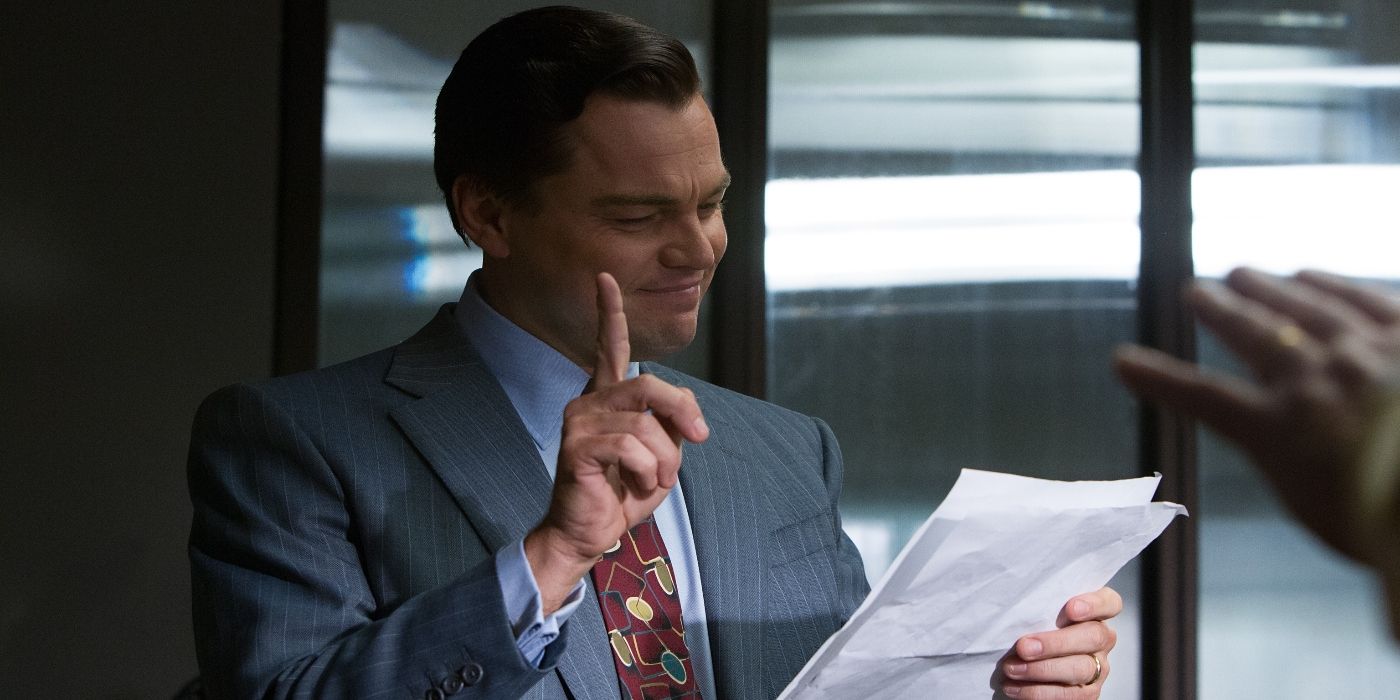

What’s important is that Belfort isn’t a genius. He’s not a particularly knowledgeable guy, but Belfort’s power is his charisma. It never mattered what he was selling as much as how he was selling it; Belfort was able to get his clients excited about the prospect of investing, even though a bit of research would have told them that the deal was bad. Belfort’s magnetic charisma was able to convince his investors to act against their self-interest. The final scene shows how Belfort has mastered this technique; if he can show an audience of potential financiers how to sell something as simple as a pen, then he can show them how to sell anything. The audience’s struggle to come up with compelling reasons to buy the pen shows just how unique Belfort’s power really is.

In many ways, Scorsese continues this theme with the film itself. As an audience member, we should be disgusted by Jordan’s crimes; he represents everything wrong with Wall Street greed. At the same time, enjoying the film means we’ve once again been caught up in one of his cons. By enjoying watching Belfort indulge himself, we’re letting him escape consequences yet again.