The Big Picture

For classic Hollywood legend, Gary Cooper, his most iconic role in his later years came so close to never happening. In an alternate universe, studios and executives follow through on their false intuitions and never cast the actor in the celebrated 1952 Western, High Noon. Today, Cooper is indelible as Marshal Will Kane, and the idea of any other star in this role is unthinkable. The role as the conflicted sheriff in the face of violence earned Cooper his second Academy Award for Best Actor, and High Noon quickly ascended as an American classic. All of this would be infeasible without the impact of Gary Cooper.

Gary Cooper’s Historic Career in Hollywood Spans Decades

The career of Gary Cooper spans generations of the American film industry. He worked in the silent era, the Golden Age of Hollywood, and the waning years of the classic studio system. The star embodied an idyllic hero who represented the average American in heartfelt dramedies and Westerns. Without the display of brute force or a larger-than-life persona, Cooper is idolized today as a relic of a better kind of society – one that Tony Soprano invokes when bemoaning the lack of the “strong, silent type” in contemporary America. His innate abilities as a captivating screen presence made him a lucrative asset in Hollywood, not to mention his gracious skills as an actor, which are defined by his naturalism and restraint. Cooper consistently worked with the finest directors in Hollywood, and in the history of filmmaking for that matter, including Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh, Fritz Lang, Anthony Mann, and Fred Zinnemann, who would direct High Noon.

How Gary Cooper Earned the Part of Will Kane in ‘High Noon’

In 1941, under the direction of Hawks, Cooper won his first Oscar for playing Alvin C. York, a decorated American soldier in World War I, in the biopic, Sergeant York. Having been a mainstay in films for two decades, Cooper appeared to reach the pinnacle of his powers. However, Hollywood, in its unforgiving practice, dismissed the star by the 1950s. Detailed in Glenn Frankel’s book, High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, reached his 50s by the time of High Noon’s production. Director Stanley Kramer, who was a producer of the film, said “Everybody felt he was old and tired.” From today’s perspective, when nearly all the prominent leading men in Hollywood are in their 50s, writing off a legend like Cooper is noticeably troublesome.

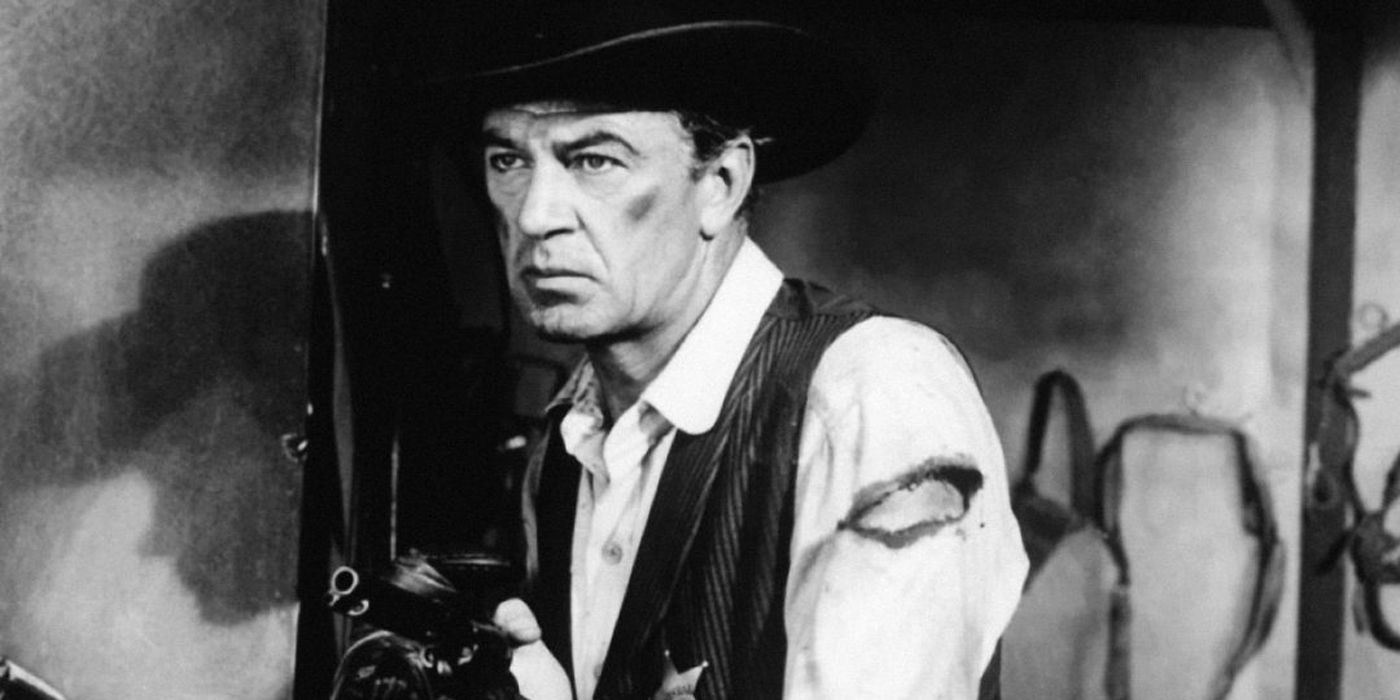

Sensing a cumbersome task ahead of him, Cooper vowed to prove to the studio and executives that he was right for the part of Will Kane. He agreed to reduce his salary. Stripping away the glamor of the typical movie star, he also volunteered to perform without makeup, highlighting the creases in his leather-saddle face. The biggest names in Hollywood were offered the role, including Gregory Peck, Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, and Charlton Heston. Peck turned down the part because he viewed it as a rehash of a previous Western role in The Gunfighter. With the other viable stars declining, Cooper, along with his associative bargains, became too enticing of an offer to turn down. Not to mention, the studio struck gold with the casting of 21-year-old ingénue and impending breakout star, Grace Kelly, as Amy Fowler Kane. Cooper’s health was a lingering concern throughout filming. He had recently undergone an ulcer operation, and his facial expression of anguish on screen is an authentic reaction from Cooper. The actor was also suffering from frequent back pains during the shoot.

The Impact of the HUAC on the Making of ‘High Noon’

Gary Cooper was not the only figure who needed to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds going against his favor. The story of High Noon is inextricable from the anti-Communism movement in America that was rampant upon the production and release of the film. The film’s screenwriter, Carl Foreman, was a former member of the Communist Party. He was subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in June 1951 and refused to indict any communist-tied colleagues in Hollywood. Foreman’s bold stance to defy McCarthyism immediately ostracized him from Hollywood and America, as he moved to Great Britain following his societal persecution. The writer would later publish his work under pseudonyms or went uncredited entirely, which was the case for his script with fellow-blacklisted writer Michael Wilson for The Bridge on the River Kwai.

As a matter of basic procedure when producing a Hollywood Western, John Wayne was originally offered Cooper’s lead role but turned it down due to the film’s allegorical ties to communist blacklisting. An advocate of HUAC’s persecution of alleged communists in Hollywood, he later stated in his infamous Playboy magazine interview that he would “never regret having helped run Foreman out of this country.” Ironically, despite his disgust for the film, Cooper’s Oscar for High Noon was accepted by none other than Wayne in the star’s absence, with Wayne describing Cooper as a class act. In the speech, Wayne jokes that he is “going back to find my business manager and agent … and find out why I didn’t get High Noon instead of Cooper.”

In a poetic demonstration of art mirroring reality, the character of Will Kane would inadvertently act as an avatar to Carl Foreman and his plight. In the film, the disillusioned sheriff must defend his small New Mexico town against a gang of killers whom he sentenced to prison. Conflicts arise when Kane, abandoned by his commonwealth, is forced to combat the gang alone. At the end of this saga, Kane bitterly exiles from the town, a fitting resemblance to Foreman’s disgraced exit from Hollywood. For Carl Foreman, his persecution from HUAC caused his career to spiral into anonymity, while Fred Zinnemann would go on to direct two future Best Picture winners in From Here to Eternity and A Man for All Seasons. Gary Cooper, with his striking performance as an antagonized, listless sheriff, cemented his status as an everlasting Hollywood legend.

‘High Noon’ Stands as an American Classic and a Defining Role of Gary Cooper

Considering that High Noon positioned a gang of outlaws as a metaphor for McCarthyism and HUAC’s witch hunt against alleged Communists, it is a miracle that the film was ever produced and released to the public. The film was a triumph, winning four Oscars, Best Editing, Original Song, and Score, alongside Gary Cooper’s win for Best Actor. High Noon had the prestigious honor of being one of the original 25 films to be selected for preservation by the Library of Congress. Fred Zinnemann’s film laid the groundwork for the structure and tone of Revisionist Westerns that became fashionable in later decades. Perhaps most substantially, High Noon allowed a living legend in Cooper to prove his skeptics wrong.