Artist and activist Buffy Sainte-Marie’s Indigenous identity has been challenged by a CBC investigation but her Piapot First Nation, Sask. family stands by the 82-year-old, calling the narrative “ignorant,” “colonial” and “racist.”

Ntawnis Piapot, speaking for the family, says the bombshell claim that Sainte-Marie has no Indigenous blood has no bearing on her belonging to the Cree family.

Piapot is the great-granddaughter of Emile Piapot and Clara Starblanket, both deceased, who adopted Sainte-Marie some six decades ago.

Piapot says Sainte-Marie connected with the Piapot First Nation after she met her grandfather at a powwow in Ontario.

“There was just things that kind of lined up to her story too,” she told Global News.

“My grandparents had 10 children and some of them died because of the Indian Act system, because they couldn’t get proper health care on the reserve and so she was at that age where one of their children passed away and they kind of connected on that.

“The adoption process, it took years — it took days and months and years of getting to know each other and trusting each other and going to ceremony and getting her Indian name (from my mushum) to finally look at her and be like, I acknowledge you as my daughter, you’re officially part of our family.”

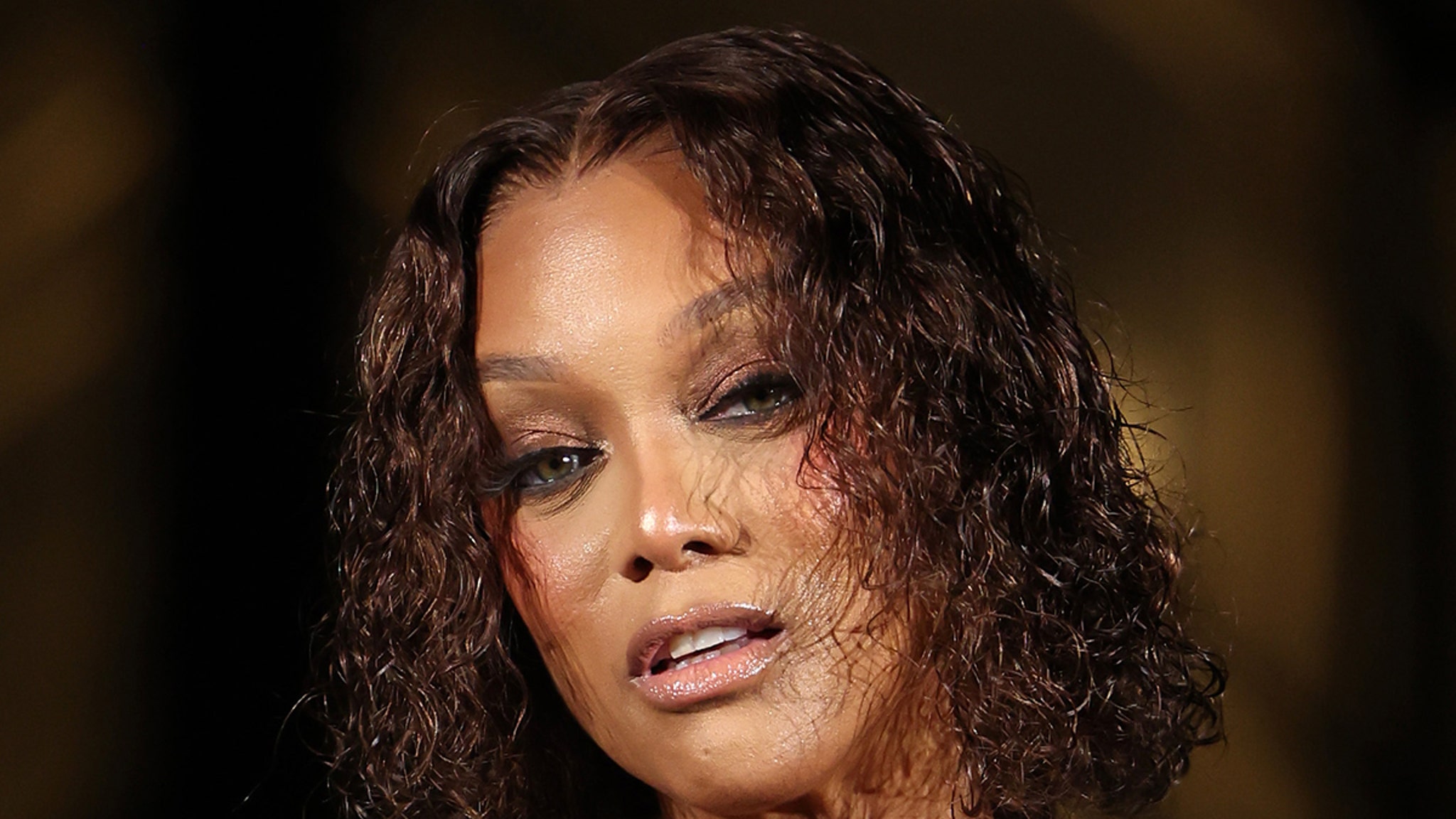

Buffy Sainte-Marie speaks after the unveiling of a Canada Post stamp honouring her legacy as a singer-songwriter in 2021.

THE CANADIAN PRESS / Justin Tang

It was done in Cree custom and while Sainte-Marie didn’t claimed proof of blood relations, she is accepted as kin because of that ceremony.

“It’s really insulting that someone would question my great grandfather’s choice and right to adopt Buffy as his daughter,” Piapot said.

“No one has the authority to question our sovereignty, we are a sovereign nation, we are sovereign people and our adoption practices have been intact since time immemorial.

“Having someone question the validity of that adoption … it’s hurtful, it’s ignorant, it’s colonial, and quite frankly it’s racist.“

Sainte-Marie claimed to have been ‘scooped’ as an infant

Sainte-Marie’s authorized biography written by Andrea Warner reads “There’s no official record of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s birth, not really. At least not a satisfactory and decisive one that answers questions before they’re asked, grounded in a family lineage with all the gifts and baggage that accompany that kind of belonging.”

The book continues, “born with the given name Beverly, most likely in 1941, on or around February 20th, and probably on a reserve called Piapot in the Qu’Appelle Valley, Saskatchewan. She is Cree.”

Sainte-Marie has said she was somehow adopted and raised in Massachusetts by a non-Indigenous family.

But the CBC investigation — none of which has been verified by Global News — challenges that. They say a birth certificate shows her parents are Italian and English and aren’t her adopted parents at all, but her birth parents. Family quoted by the CBC say there is no Indigenous heritage in their family.

Responding this week ahead of the CBC report Sainte-Marie in a post on social media, said “I am proud of my Indigenous-American identity, and the deep ties I have to Canada and my Piapot family.

“I may not know where I was born, but I know who I am.”

In a recent podcast episode, Sainte-Marie spoke about her identity and how she routinely tries to correct misconceptions.

“There’s been confusion regarding my Piapot adoption for instance,” she said. “I was adopted into the Piapot family, not I was adopted out of Piapot reserve. That makes a big difference.”

This recent clarification does however go against the biography on her website and statements made by her biographer in the past about being a part of the 60s scoop.

Among her many accolades, Sainte-Marie won an Oscar in 1983 for best original song, starred on six seasons of Sesame Street, influencing the show’s storylines, and founded the Nihewan Foundation — an organization dedicated to improving education of and about Indigenous people and cultures.

Trending Now

‘Young and the Restless’ star Christian LeBlanc reveals cancer diagnosis

Big babies: Mom wins court case to evict her 40-year-old sons in Italy

Buffy Sainte-Marie is pictured (centre) with Emile Piapot and Clara Starblanket.

Buffy Sainte-Marie / Facebook

Adoption processes have been happening in First Nations communities for centuries.

The Assembly of First Nations says customary adoption “usually takes place between members of the immediate or extended family, although it may also involve people close to these families, such as friends or community members. By its nature, adoption varies from nation to nation.”

The allegations against Sainte-Marie caused a shock throughout Indigenous communities with reaction mixed, from disappointment to anger to support, spawning hashtags like #IStandWithBuffy.

News stories that challenge Indigenous identity — like Joseph Boyden, Michelle Latimer and Carrie Bourrasa — all raise the same question: Who has the right to decide who is and who isn’t Indigenous?

Among the many points to consider in determining identity, ultimate decision-making power lies in the hands of communities, says Metis lawyer Jean Teillet who in the wake of several high-profile Indigenous identity matters, recently penned what’s considered the gold standard for addressing identity fraud.

As well, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People states, in Article 3, that “Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination.” Self-determination means “the sovereign right and power of the Indigenous group to decide who belongs to them, without external interference.”

If the Piapot family claims her, is that enough?

“No one should be able to question if (Sainte-Marie) is from Piapot because we claim her,” said Piapot, who is a former CBC journalist. “She’s claimed. She’s not kicked out. She claims us, we claim her, end of story.”

Her family wants people to keep an open and critical mind as the story unfolds.

“Think about whose voices are included in this story, whose voices are not included in this story and why did that happen? And most importantly, who is telling this story? What is their track record for telling Indigenous stories?”