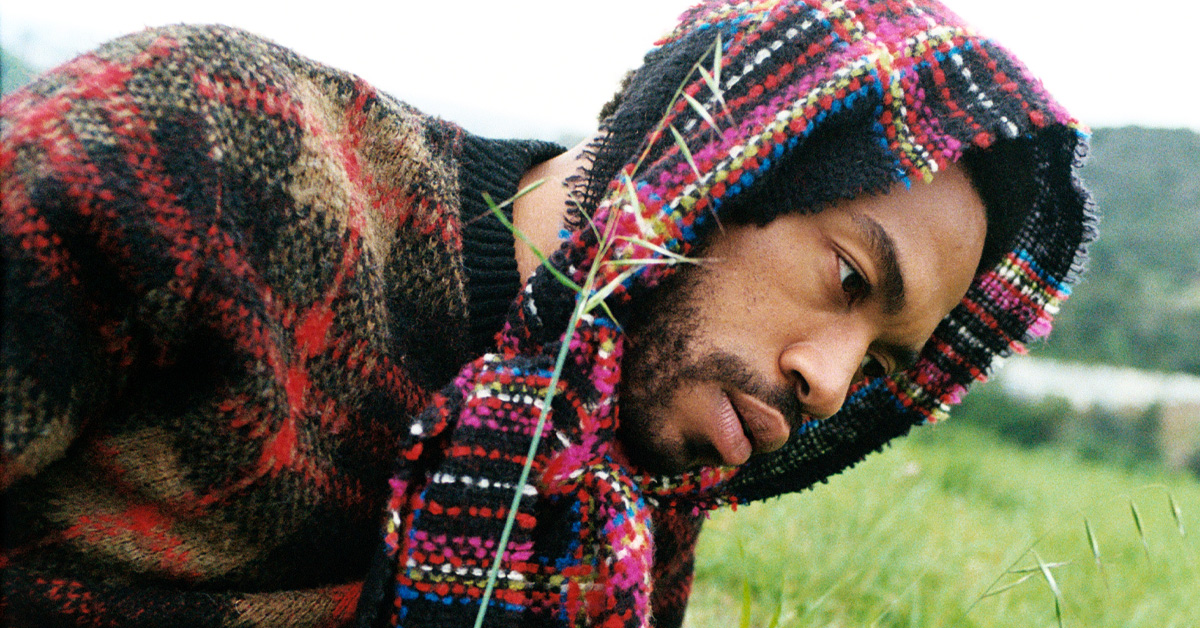

Kevin Abstract appears on the cover of the Spring 2024 Issue — head to the AP Shop to grab a copy.

When Kevin Abstract was a hyper-online teenager, he watched Corpus Christi whiz by through the back windows of public school shuttles, blasting torrented MP3 files. Over the past decade or so, he’s become something of a savior to the crowd he once embodied: cynical young people cradling cracked iPhones, wax-coated earbuds, and pirated media en route to uncertain futures. Born Ian Simpson, he’s 27 now, a far cry from school buses and their rearmost regions. But he isn’t necessarily removed from existential uncertainties — and as much as he’s grown up, those uncertainties remain an enduring relic of his storied past. Last year, after a prolonged period of public prefacing, he pulled the plug on BROCKHAMPTON, the boy band that took him from Texas’ suburbs to the world’s loftiest stages. He’d been a solo artist before, but being alone, now, meant something vastly different. The back of the bus is fun when you’re with your friends. When they get off, the only voices left are in your head.

Read more: Nirvana’s 1992 cover captures a band breaking into the mainstream

On those after-school rides through Corpus Christi, the voices in Simpson’s head belonged, mostly, to a hodgepodge of indie-rock staples and internet anarchists. Today, on a Friday afternoon in February, he’s celebrating a friend’s birthday in Silverlake, straining to remember the music that soundtracked his formative years. “Dark [Twisted] Fantasy… In Utero… Modest Mouse stuff… Bastard by Tyler, the Creator… Nostalgia, Ultra… wait, I’m missing someone super important,” he drawls on a Zoom call, between lengthy pauses. “Oh. I never talk about how much I would listen to Mariah Carey.” Carey isn’t the only influence he’s freshly learning to wear on his sleeves.

Post-BROCKHAMPTON, he’s seemed hellbent on holding true to those unsung high school heroes — the Mariah Careys, the Modest Mouses, the Kurt Cobains — as a conduit for holding true to himself. Long after he traded suburban Texas for cosmopolitan Cali, he put out ARIZONA BABY, a purgative album about fleeting todays and foggy tomorrows. A track called “Corpus Christi” asked questions he continues to grapple with, half a decade later. “At what point do I do it for myself,” he sings, “instead of thinking ’bout the set?”

You might interpret “the set” in one of two ways: There’s the band, obviously, but also its newly orphaned fans, who fell in love with a particular sound throughout the 2010s, and must now grope around for its detritus. If there’s any indication that Simpson’s priorities have shifted — from pleasing “the set” to pleasing his gut — it’s in the fact that Blanket, his most recent album, sounds a lot more like his influences than his reputation. Where BROCKHAMPTON once followed the blueprints of rowdy early aughts sensations, who melded hip-hop bravado with punk-rock outsiderism, the new iteration of Kevin Abstract is placid, more into whispering than yelling. In certain spots, say, the arena-sized title track, his album sounds revved-up, like a quiet friend learning to project his voice. More dutifully interspersed, though, are the sobering moments: ruminations stripped of braggadocio, conclusions that feel, simultaneously, like deaths and rebirths. About midway through “Voyager,” Simpson’s voice is a sullen mutter against torrents of downpicked guitar — quiet enough to seem wistful, but barely loud enough to feel, even if faintly, assured. “For the first time,” he sings, “I feel myself growing older.”

It would make sense that only now, nearly a decade removed from his molten ascent, he’s getting the space to feel himself change. Simpson belongs to a pivotal progeny of information-era denizens, who turned frenzied media consumption into tangible, on-the-ground movements: Odd Future, the A$AP Mob, Pro Era, the Internet. He was a high school freshman when the seeds of BROCKHAMPTON were sown, more accustomed to the backs of classrooms than the fronts of festival stages. While peers were graduating, in real time, from the forums he stalked to the arenas he aspired to, he followed along on his phone, glued to the prospect of art on one’s own terms. At a certain point, it became painfully apparent that there was more to life than school, suburbs, slacking — and if he wanted it, he would have to act, and grow, very quickly. “When I was 14, my sister and my mom asked me something about college,” he says. “I was like, ‘Whoa. I only have, like, three years left.’” The more he thought about them, the more they seemed to be running out.

It’s 2024, now: More than three years have passed. On a recent business trip to London, he impulsively made a new Letterboxd account, something of an attempt to rein in — or reckon with — lost time. Over a single day, he logged 25 films. (“I use it as a diary, man.”) Among these titles was The Social Network, the 2010 Mark Zuckerberg biodrama that narrativized Facebook’s founding. Years ago, around the same time that the “college” question came up, his sister took him to see it at the neighborhood Cinemark, a brief respite from friendless school days and looming anxieties. “Made BH bc of this movie haha,” he wrote, casually, in a rambly Letterboxd review. “Made me chase the vision.”

Over Zoom, he’s more detailed. “I watched the movie, and was left with this feeling that I couldn’t escape, really,” he says. “It lingered over my entire freshman year. ‘Empty’ was the first real music video I made. I remember coloring that with HK [Sileshi], and asking him to lower the exposure, bring out the blues a little bit more, fuck with the contrasts, make it a little bit more saturated, but still keep it moody and dark. And the more I did that, the more I realized I was pulling from that experience: watching The Social Network. It wasn’t the first time I had seen [David] Fincher’s work, but it was the first time I recognized the tone of it. I believe we see ourselves in the things we enjoy.”

Like any other kid who saw The Social Network when it came out, Simpson definitely enjoyed Facebook. But he enjoyed other things, too: things like telling stories, messing around with cameras, asking people questions, combing through records with cool covers. When he was 13, he started a short-lived blog; one of his first pieces was a heartfelt obituary for Michael Jackson. (He’s still quite the MJ fan: In preparation for soon-coming shows, he’s been studying footage from the Bad tour.) Come high school, he wrote a variety of op-eds for the school newspaper, including a personal essay about being Black in the suburbs of Texas.

In a sense, it was an early glimpse of what would soon be a familiar routine — the publication of personal truths, met with mixed reviews from its faceless consumers. “It felt so punk to be doing that in 2011,” he says. “Some people at my school felt weird about [the essay]. But no one ever said it to my face.” Somewhere behind the wall of white noise, there were other estranged suburbans, who saw themselves in what Simpson wrote, and deeply resonated with it. Both as the ringleader of his band and, now, a full-time pursuer of personal projects, he’s been an expert at finding the fringes, then making them the future — forums to festivals, cinephilia to celebrity. Today, with much of that legacy established, he still hopes others might see themselves in the meandering trail he leaves behind.

One thing Simpson has seen himself in, over the past few months, is deadAir Records, a young label that foregrounds inventive, boundary-pushing acts. A day before our interview, he was in Santa Ana to see a performance by Jane Remover, an eclectic signee whose prolific practice is a constant source of inspiration. He’d been obsessed with finding things that “painted unique pictures of ideas for the future,” and artists affiliated with the label “just kept popping up.”

Among those artists, aside from Jane Remover, was Quadeca, a 23-year-old wizard who puts pedal-drenched guitars, rap-adjacent vocals, and a million disparate influences into a blender to concoct wicked catharsis. Months ago, he released one of several singles for SCRAPYARD, a compilation album of loosie tracks recorded over the past two years. Simpson loved it. “He DMed me like, ‘Where are you,’ and I was like, ‘I’m in LA,’ and he was like, ‘What?’ For some reason, people tend to think that I emerged out of the woods,” Quadeca says, in a phone call. “He said, ‘We should make something,’ and I was like, ‘How’s tomorrow?’”

The following day’s studio session was quick, synergetic, “a successful rizzing” — all the things that Quadeca, a longtime fan of Simpson’s, might never have dreamed of in high school. “I was very captivated by the moment,” he says, of the BROCKHAMPTON 2010s. “I feel like every artsy white boy wanted to be in BROCKHAMPTON. But I was also inspired by Kevin’s solo work. There’s this song, ‘Empty,’ that I really love. It’s on [American Boyfriend]. When we were making our song, I think I was very specifically trying to get the swag of ‘Empty.’”

The track that came out of those sessions was “TEXAS BLUE,” a head-boppy elegy that launches “Empty”’s angst, headfirst, into the hope it seemed to be scrounging for. When Simpson made “Empty” in 2016, growing pains were fresh, and he was wearing the welts on his sleeves. It’s disarming, eight years later, to revisit the section where he lists the pieces of himself he hates: his yearbook photo, his passport, his last name, everything said last name represents. As much as his upbringing may be something of an anomaly, its emotional baggage isn’t at all. When we were as old as he was, then, we hated things about ourselves, too. And some of those things, we still do resent — even if we suppress them under swagger, talk around them in therapy, finesse them via filters. Growing up isn’t about suddenly having everything you wanted; it’s about reckoning with what you lack, and finding strange comfort in the bumpy pursuit of it. “I’ll be honest,” the pair sing in unison, as “TEXAS BLUE” comes to a close. We should be, too.

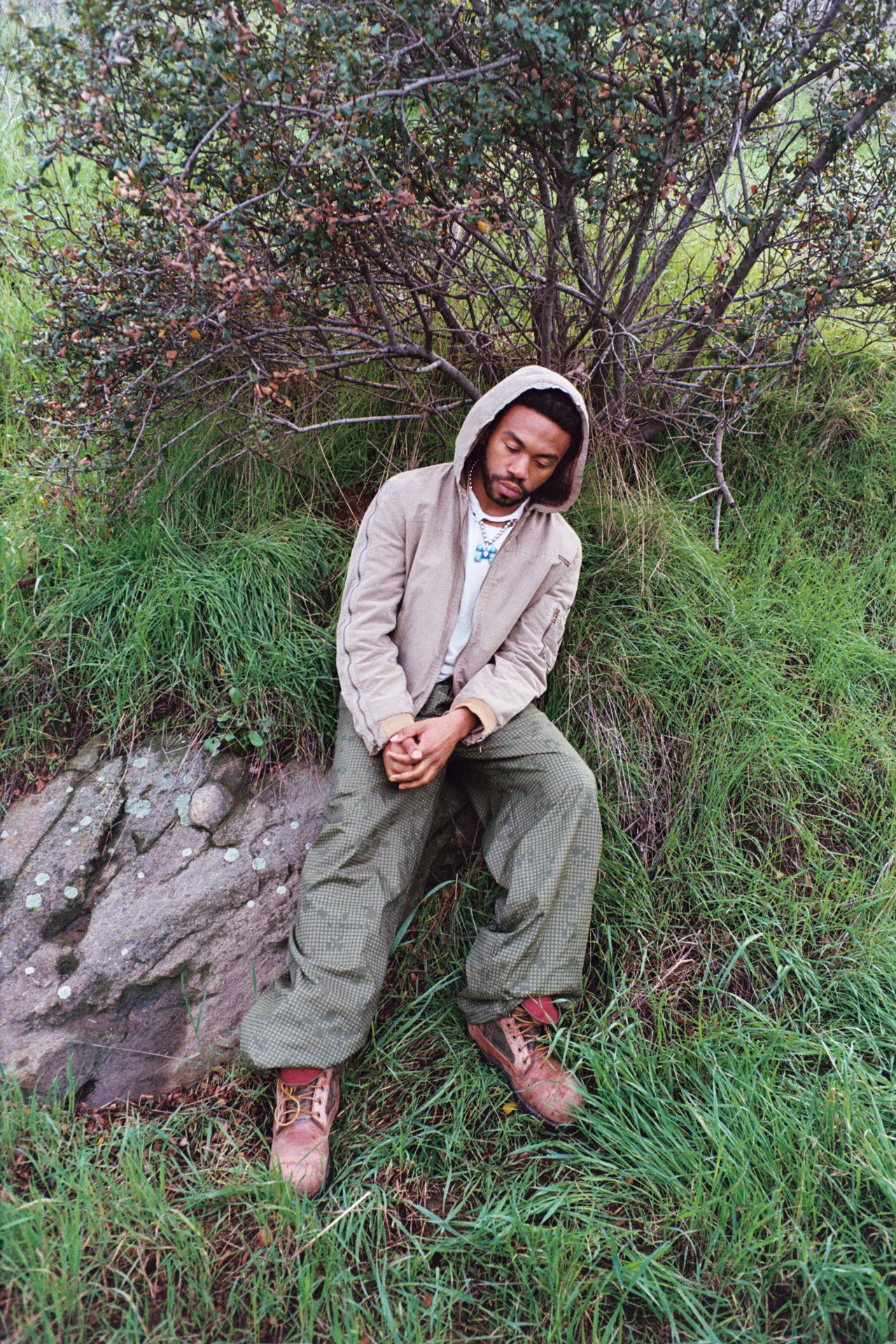

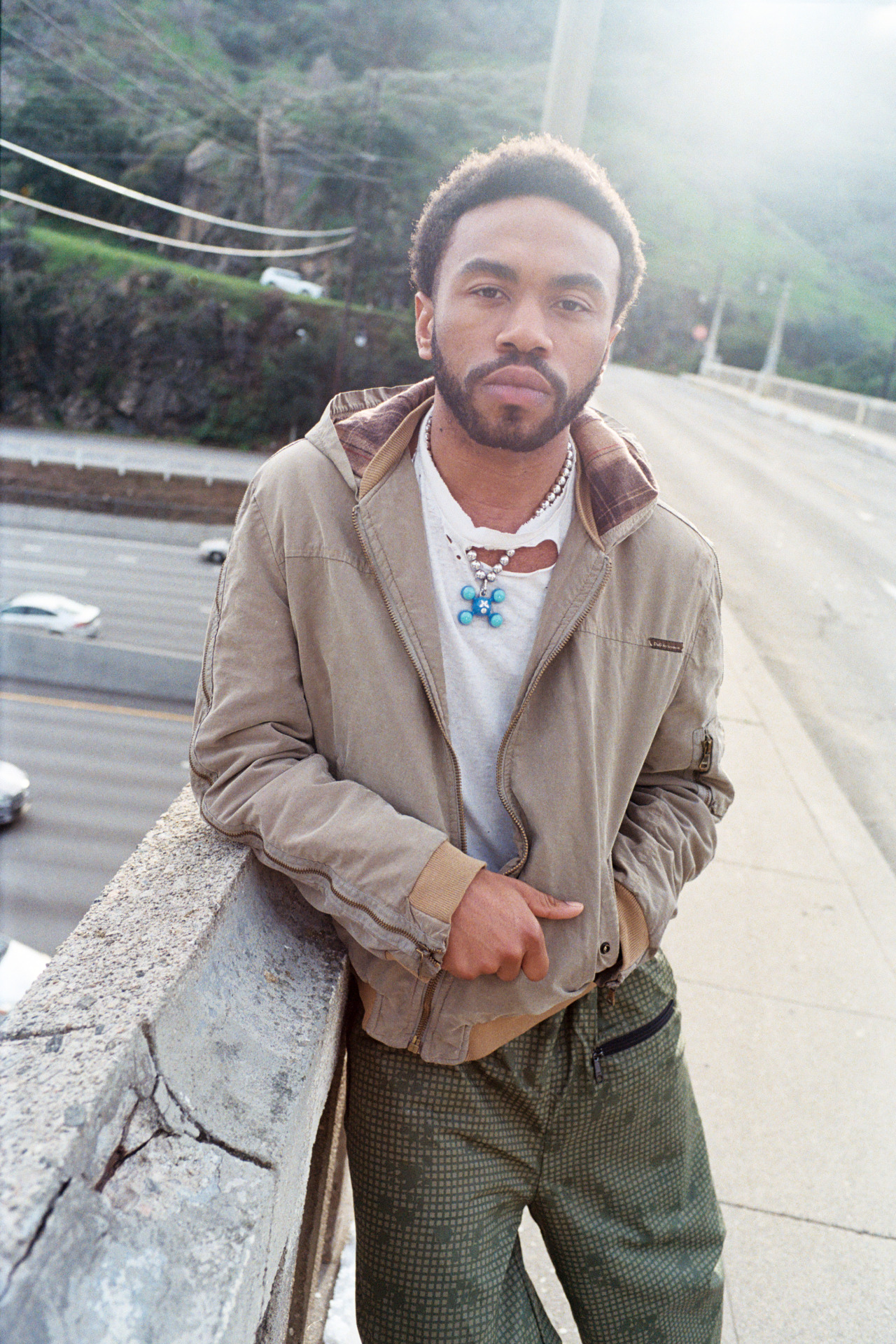

Photos by Adali Schell

Styling by Jack Bat

Makeup by Mel Daniel Sandoval