Huddled together under pop-up tents in a city square under glittering glass highrises, pounded by hail and rain, the Punjabi community of Surrey, British Columbia, gathers for the annual 5X Fest, a celebration of South Asian music and culture in this heavily South Asian suburban city of greater metro Vancouver.

As the clouds clear and the sun comes out, music fans flood the front of the stage, singing along with artists and posing for selfies. It’s what you might expect at a community festival, families with kids and college students with backpacks dancing along. But artists at the festival, and the Punjabi music industry in general, are enjoying global stardom, clocking in hundreds of millions of streams and views—over a billion total for some.

More from Spin:

Bon Iver Teasing First New Album In Five Years

We’ve Seen the Future, and It’s JHAYCO

R&B Artist Lekan Wants to Help Us and Heal Us

Surrey’s the key to a global wave of Punjabi music sweeping the West, selling out stadiums, packing Coachella, appearing on American late night TV, and picking up acclaim without most in the West understanding the language of the songs.

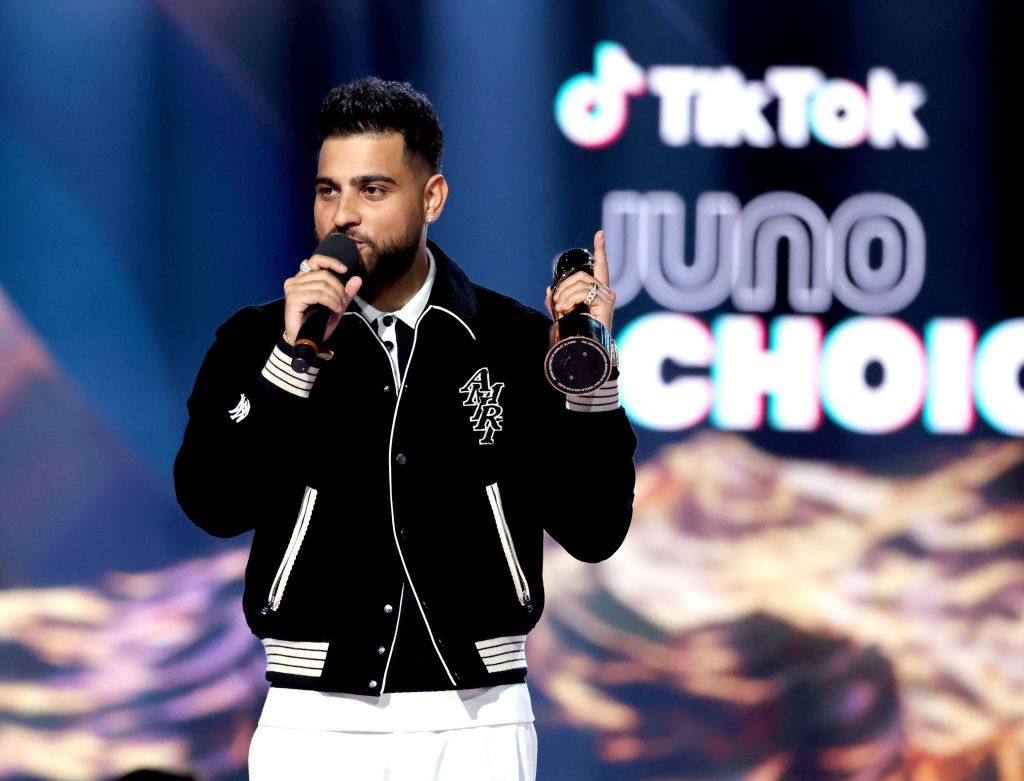

There’s not even a name for this new music. It’s not really bhangra, the Punjabi dance tradition that had its own global rise in the early aughts with Panjabi MC’s catchy “Mundian to Bach Ke” (feat Jay-Z). It’s mostly just referred by whatever seems appropriate for a singer’s genre, with “Punjabi” added before that. AP Dhillon, who just signed to Universal’s Republic Records and has an Amazon Prime documentary about his rise from Victoria, BC, could be Punjabi R&B or Punjabi Pop. AR Paisley, who lit up the crowd at 5X Fest, is Punjabi Rap, and the biggest star of the moment, Diljit Dosanjh, who recently sold out the 54,000 seat B.C. Place stadium in Vancouver, moves fluidly between Punjabi Pop, Drill, Bollywood, and even film roles.

With a mainstream music industry in Canada and the US that’s largely ignored this rise, it’s perhaps not surprising that these new global stars have built their own industry from scratch. They’ve done so under pressure, with violence and international political tensions nipping at the heels of this new music movement. It’s also not surprising that few outside the scene seem to know that Surrey, a humble satellite suburb of Vancouver, has played an outsized role in building this new wave of artists. It’s all happening here at 5X Fest and behind the scenes, a community of music makers and artists whose rapid rise to global superstardom has been rocky at times, but is moving towards a triumph for the Punjabi diaspora.

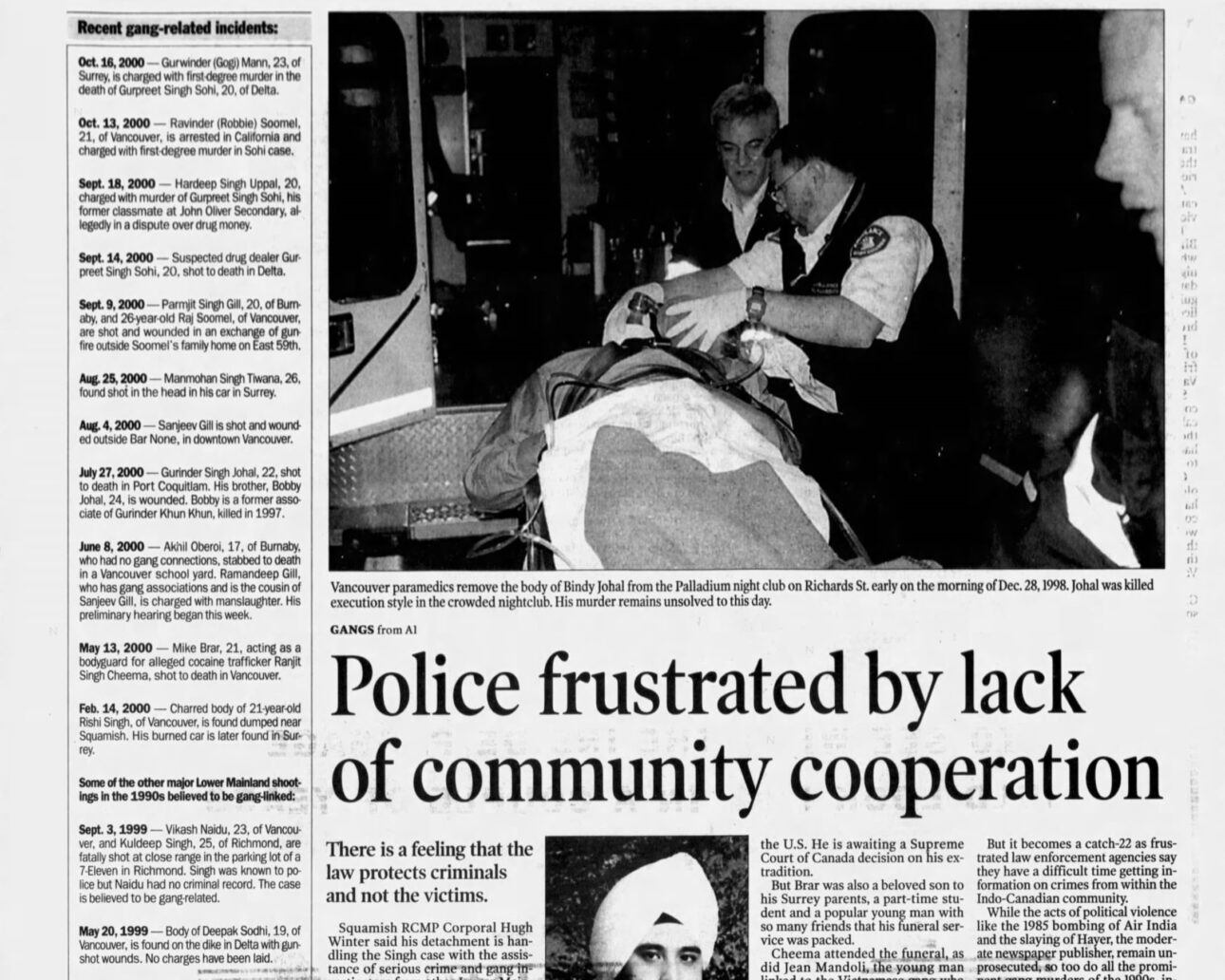

Surrey’s part of the Greater Vancouver area, a network of suburbs home to the city’s vast immigrant populations. Everyone from Chinese to African to French-Canadian to Scandinavian communities thrive in these cities, well outside downtown Vancouver, but Surrey’s known for having the second largest Sikh community outside of India. Ask a Vancouverite about this suburb (which is a little over 20 miles out) and you’ll likely sense apprehension: Surrey is still burdened with its reputation from ‘90s South Asian gang activity and a reputation for high crime that hasn’t matched the largely improving stats for a decade or so. Many in Surrey told me they see the persisting branding as due to Canadian racism.

Roaming the streets and shopping malls of Surrey, you see Punjabis everywhere, families spending time with children and elders. As a religion, Sikhism believes in equality and charity, in building community through good deeds. Still, violence lurks at the edges of British Columbia’s Punjabi music scene. The two biggest stars of the moment, AP Dhillon and Karan Aujla, have both had homes they’re affiliated with shot up, with one of Dhillon’s houses getting peppered with rounds even this month.

The City’s Festival Events Team felt that it was not in the best interest of public safety to support this performance.

City of Surrey on vetoing Sidhu Moose Wala

When the greatest Punjabi voice of a generation, Brampton singer Sidhu Moose Wala, was booked to perform at an early 5X Fest in 2019, Surrey’s city council requested his removal from the lineup, following a police assessment which cited violence at his shows earlier that year, including gunfire in Calgary and a stabbing in Surrey. The City of Surrey’s General Manager of Parks, Recreation, and Culture, Laurie Cavan, then told the Daily Hive that “the City’s Festival Events Team felt that it was not in the best interest of public safety to support this performance at a family friendly, all ages event.” However, the view of pretty much everyone I talked to in the community around 5X Fest was that Sidhu’s cancellation was due to fear mongering and racism from city authorities—part of a pattern of stereotyping—rather than legitimate safety concerns.

Surrey born and based DJ and producer Intense, responsible for some of the biggest hits in this new wave of Punjabi music through his work with megastars Diljit Dosanjh and Surrey’s own Karan Aujla, remembers it well. “I remember talking to [Sidhu] about it and he was really, really down,” Intense says. “He’s like, ‘What have I done to anybody, man? I’m just a fucking normal guy.’”

5X Fest’s Executive Director Harpo Mander remembers it as a flashpoint that pushed the festival to seek more exposure—to change perceptions. “The organization lost its deposit, the crowd was mad, sponsors were upset. It was a big deal and it was a really big motivation for the organization to start pushing even harder for what it really believed in.”

I was told to keep Karan [Aujla] off my lineup or I wouldn’t get my permits

Former 5X Festival Director Tarun Nayar

5X Fest’s Executive Director at the time, Tarun Nayar, remembers that following Sidhu’s removal from the lineup, Nayar was told by city staff that future lineups would have to be vetted by the City Council. “The following two years I proposed Karan [Aujla],” he says. “Both years I was told the Council chatted with the RCMP and I was told to keep Karan off my lineup or I wouldn’t get my permits.” Whatever the credibility of security concerns around Aujla, due to the scale his fame has since reached “the window has closed” on bringing him to 5X Fest, says Mander, a point of frustration for a hometown music festival looking to present its own global star.

In many ways, Sidhu Moose Wala was the face of this new wave of music, the Punjabi Tupac. He came from rural roots in India, singing epic vaar ballads of Sikh heroism in war, according to Surrey-based journalist Jeevan Sangha. He moved to Brampton, Ontario, as an international student, and melded his roots in Punjabi song with the hip-hop he loved. His songs started to blow up around 2020 with classics like “Old Skool” and “Tibeyan Da Putt”, and with music videos featuring his signature blend of rural Sikh farm life, urban Canada, and guns.

Moose Wala’s charisma, lyricism, and high production values inspired legions of fans. “[He] created a phenomenon that I’ve never seen before,” says Sangha. “He created this fandom that was so loyal and fierce around him, and also he was very politically engaged. He talked about things that a lot of other artists in his generation just weren’t really talking about in the same way, [like] Sikh sovereignty. He talked about the rights of Punjabi people. He also was one of those people who left India but talked about giving back to his village and coming back to his parents. He brought these traditional, really, really complex lyrics.”

Moose Wala’s killing in a 2020 ambush in Punjab sent shockwaves through the Punjabi music world and beyond. Drake paid homage. This year in Surrey, Sidhu’s presence loomed over the 5X Fest. Fans held a painting of him aloft in the crowd, and his face was spotted on hoodies and gear. When AR Paisley opened up his hit song “Drippy” featuring a posthumous duet with Sidhu, the crowd sang the slain star’s verses.

The community’s love for Moose Wala and desire to honor him at the festival is a sign of his talent and charisma, but also some of the pressures Surrey’s Punjabi community lives under. Tensions between the Sikh independence movement and the Indian Government play out today on Canadian streets. In June 2023, a local proponent of Punjab seceding from India to form ‘Khalistan,’ an independent Sikh homeland, was shot dead in Surrey. Hardeep Singh Nijjar was slain in the parking lot of a gurdwara (Sikh place of worship) where he served as president. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau blamed “agents of the Indian Government” for masterminding the killing—a claim New Delhi denied. This year, three Indian nationals were charged with murder and conspiracy, while a parallel U.S. case is being heard in a federal court in Manhattan.

Jeevan Sangha, who doesn’t live far from Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara, the site of the shooting, says that it has given rise to more activism: “His very tragic killing has emboldened people to speak their mind more than I saw before.” Mander sees it as a chance for the community to unite. “They respond with their hearts wide open,” she says, “whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. We’re the same community that rallies at the exact same spot when the Vancouver Canucks win the playoffs, right? And then we’re also the same community that comes together when Sidhu Moose Wala dies, and we go to the exact same spot when we’re protesting for the farmers. And when the president of their temple gets assassinated, like ten minutes from home, they come together in the same way.”

So what’s behind the global rise of Punjabi music, especially as it’s being widely discovered by Western audiences with likely little idea what the singers are saying? For artist manager Jashima Wadehra, the answer is simple. She points out that “oppression and love are not unique to any one language, they are universal truths.” For Intense, he sees the music’s danceability as key. “Punjabi music is a dance, right? You gotta make sure that you can dance to it, you can move to it. It’s very high energy. They’re singing from their diaphragms, they’re belting it out, almost like opera. Then the fact that we’re able now to mix these elements, with hip hop and R&B, it makes it more relatable.” For Sangha, it’s tied to the immigrant experience, introducing Punjabi youth newly arrived in Canada to new sounds and ideas, to something bigger than themselves. She finds the scrappiness of these immigrant artists who are now building empires in the music industry compelling.

The divide between incoming Punjabi international students and artists like Intense who were born and raised in Surrey is a key part of the way this music has developed. Canadian producers like Intense, or DJs like Hark, who performed at 5X Fest have no problem bringing in a slew of Western influences (Intense talks about going for a synthwave vibe for his track “Excuses” with Dhillon and Gill which has half a billion streams on Spotify), but the students, like Sidhu or Aujla, are the singers who are keeping this music almost entirely in the Punjabi language and who are known for their lyricism.

“I work with a lot of students in terms of production,” says Hark from his studio outside Surrey, along the Canada-U.S. Border. “You can’t even compare somebody like me that was born here. There’s no way, no matter how much Punjabi I know, that I’ll be able to speak it to the depth that they can speak it. When you’re singing, you’ve got to really just flow, and they’re able to flow in a different way than we can.”

Another key to the rise of Punjabi music out of Surrey is the lucrative Punjabi wedding market. With huge family weddings running multiple days and a never-ending demand for the hottest DJs and best singers, most of the artists coming out of Surrey cut their teeth on the wedding circuit. Hark got his turn at the decks at the tender age of 12, and Intense perfected his sound by remixing Punjabi hits with American hip-hop beats. The tech and equipment behind big music videos and huge live shows in Punjabi music often comes from the wedding industry, and it also sustains singers by offering well-paid private shows to large audiences. “There wasn’t shows,” Intense says about starting out. “Your venues were wedding parties, and those are big venues with a ton of people. Why play for 50 people in a club when you can do it for a thousand people at a wedding?”

The other marker of early success is now social media, where singers are being discovered and signed based on their virality. Surrey singer Raman Bains sees the next generation of Punjabi artists looking for that one viral hit on socials that can launch them and laments the lack of support for building careers. The industry is flooding Surrey looking to follow the money, but Bains hopes they’ll stay to support rising artists and to help build something larger. Since he grew up in a musical household with a father trained in North Indian classical music, he also remembers an earlier era of Punjabi music where audiences were focused on the quality of the singing. “When [my father] was making music, you had to be good at singing. Otherwise, why would you record? But I also understand that, in today’s day and age, it’s not about you singing. It’s about how you make people feel. Can they connect with you?” This feeling of connection was palpable at 5X Fest, as artists frequently jumped into the crowd to take selfies or to turn the mic over to audience members singing along.

Sometimes you just need somebody to break some ceilings for you to think it’s possible.

DJ Hark

With the eyes of the world on the Punjabi community now, where will the music go in the coming years? LiveNation’s already banking on major Punjabi shows in huge venues, and Warner Music Group is moving in on the scene too, starting up a new record label, 91 North Records and signing Surrey artist Chani Nattan. Charlie B, director of A&R for the label, recognizes Surrey as the heart of the new wave of South Asian music, saying, “91 North Records was created because we recognized the potential that exists around sharing the incredible music being made by these artists with the world, and wanted to make this potential a reality.”

Even with stars like Nattan rising from Surrey, there’s also a bubbling underground that has its sights on something new: underground hip-hop cyphers. These informal gatherings are picking up speed on social media and introducing a new group of Punjabi rappers through videos of freestyle rap battles. And the possibility of becoming the next Diljit Dosanjh is always there, especially after he sold out Vancouver’s sports stadium. “It was definitely a moment,” Hark says, speaking of Diljit’s local show, “and he did that in a very short period of time. So I think a lot of these kids are like, ‘Okay, it’s possible, right?’ Sometimes you just need somebody to break some ceilings for you to think it’s possible.”

Most artists I spoke to used Bad Bunny as an example of where Punjabi music is heading, since the Spanish language barrier hasn’t kept anyone from enjoying his music and becoming a fan. Punjabi artists are also watching Afrobeats and UK drill music, looking for ways to collaborate and expand their markets as they break into the mainstream.

But for Wadehra, it’s not even a question of whether the mainstream has accepted Punjabi music yet. “What is mainstream?” she asks. “What does that word mean? Because it either means white or it means numbers. And if it means numbers, we’re already doing those.” When asked about where he hopes Punjabi music will go in five years, Intense’s answer is perhaps the simplest: “I don’t even hope anymore,” he says. “It’s already happening.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.