If you ask any adult ‘80s kid how they’d define their childhood, they likely wouldn’t list shoulder pads and fluorescent leg warmers. Instead, it would be key cultural moments.

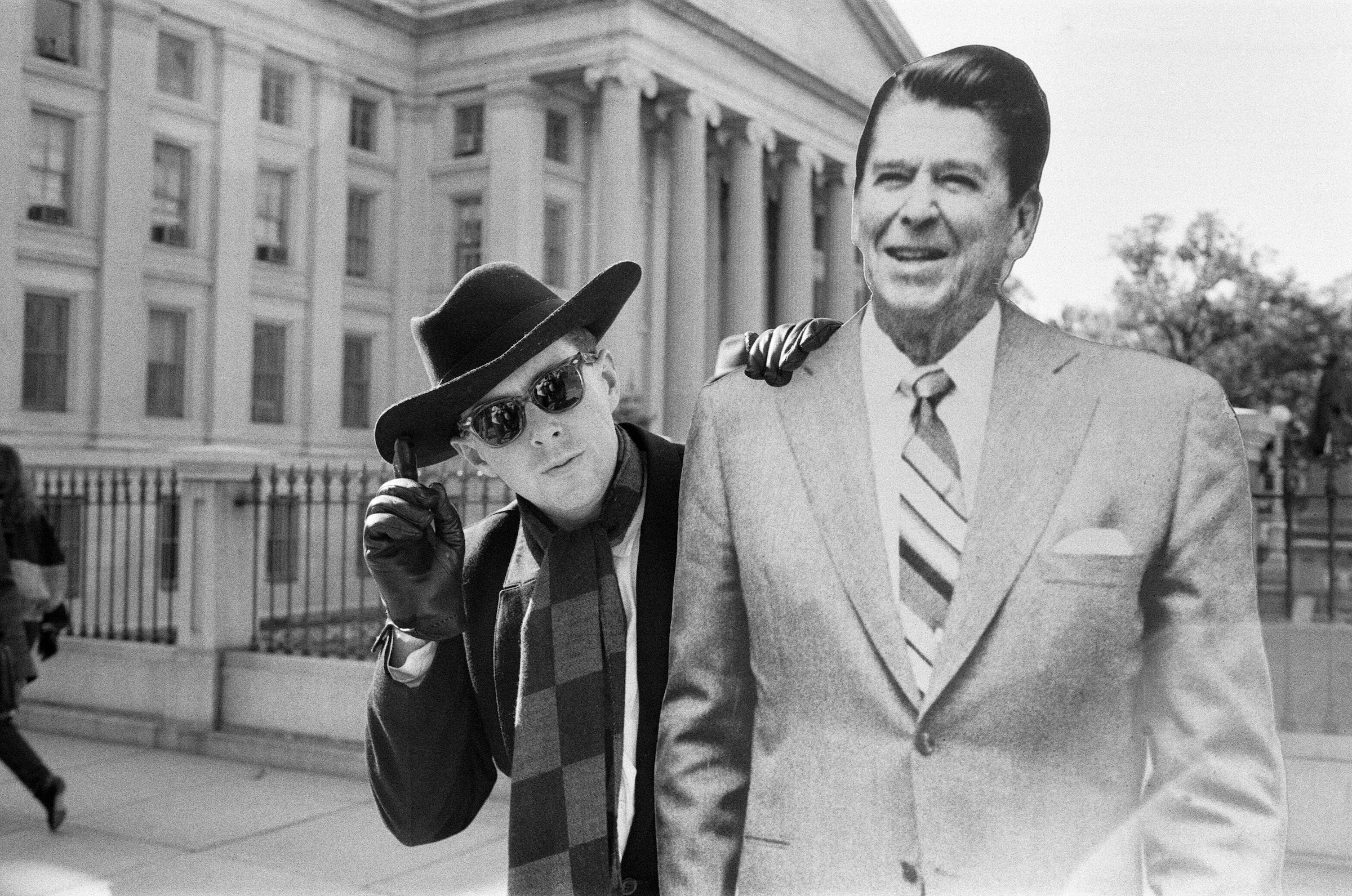

In 1984 we couldn’t have known that, in just two years, classrooms would gather around rolled-in box television sets to watch the Space Shuttle Challenger explode in real time, taking the lives of seven astronauts, including teacher Christa McAuliffe. President Ronald Reagan ruled over the decade, serving two terms from 1981 to 1989. AIDS had officially become a “crisis.” And what many try to forget was the constant threat of Russia and nuclear disaster (the Cold War wouldn’t officially end until 1991), something that became a topic of our daily vernacular, almost as much as kickball or the warm boxed milk we drank every day at lunchtime.

More from Spin:

5 Albums I Can’t Live Without: The Fray

U2 Raid Vaults For ‘Atomic Bomb’ Companion Album

Johnny Marr Talks Tour, ‘Boomslang’ Reissue, Advice For Oasis

The music of 1984 is a definite dual, dichotomous reflection of the need for expression and escape. And while there were definite genres for different stations, being raised on radio gave listeners an eclectic taste—whether they wanted it or not. By 1984 the new British invasion was in full swing, bringing a new synth-driven sound, and MTV (in its third year by 1984) actually showed us who these musicians were—and we were hooked.

If you were old enough to get away with it (or were a proficient enough liar), you would do anything to experience these bands live: waking up in the 2:00 a.m. darkness to trek over to ticket outlets to wait in line (the inability to drive couldn’t keep us away), camp out with sleeping bags, stand in the shivering cold until retailers opened in the early morning for business.

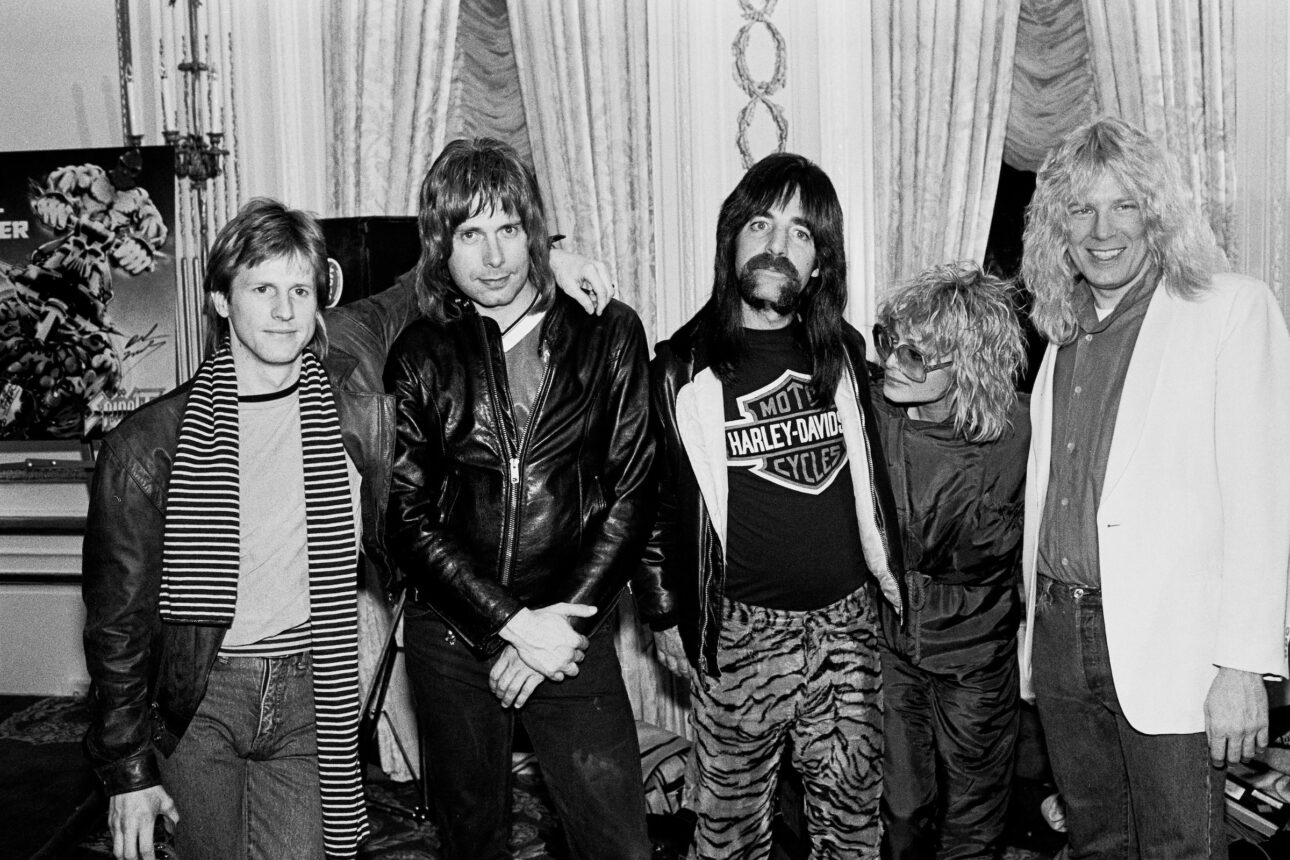

The same station that played the Scorpions’ ninth studio release, Love at First Sting (with its controversial album cover), could also play singles from Wham!’s bouncy chart-topper Make It Big. Then you might hear new music from Cocteau Twins, Lou Reed, or even the Spinal Tap soundtrack—all groundbreaking in their own way, all released in 1984.

But none of them made our editors’ list. There was simply too much great music that year.

Ringing in 1984, there was so much talk about George Orwell’s 1949 novel depicting a dystopian society in full, horrifying swing. There seemed to be a collective sigh of relief—almost a joke—that the actual year was nowhere near the threat of a subservient dictatorship. No way did technology rule our lives back then—that was almost laughable. A world where we were being watched—by Big Brother or surveillance—seemed utterly preposterous.

One quote from the book in particular—“We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness”—may best sum up the list below. From fun play-it-loud rock albums to introspective feelers, all are reflective of the time, all still remarkable now.

— Liza Lentini, SPIN Executive Editor

Bob Guccione Jr., Acting Editor in Chief

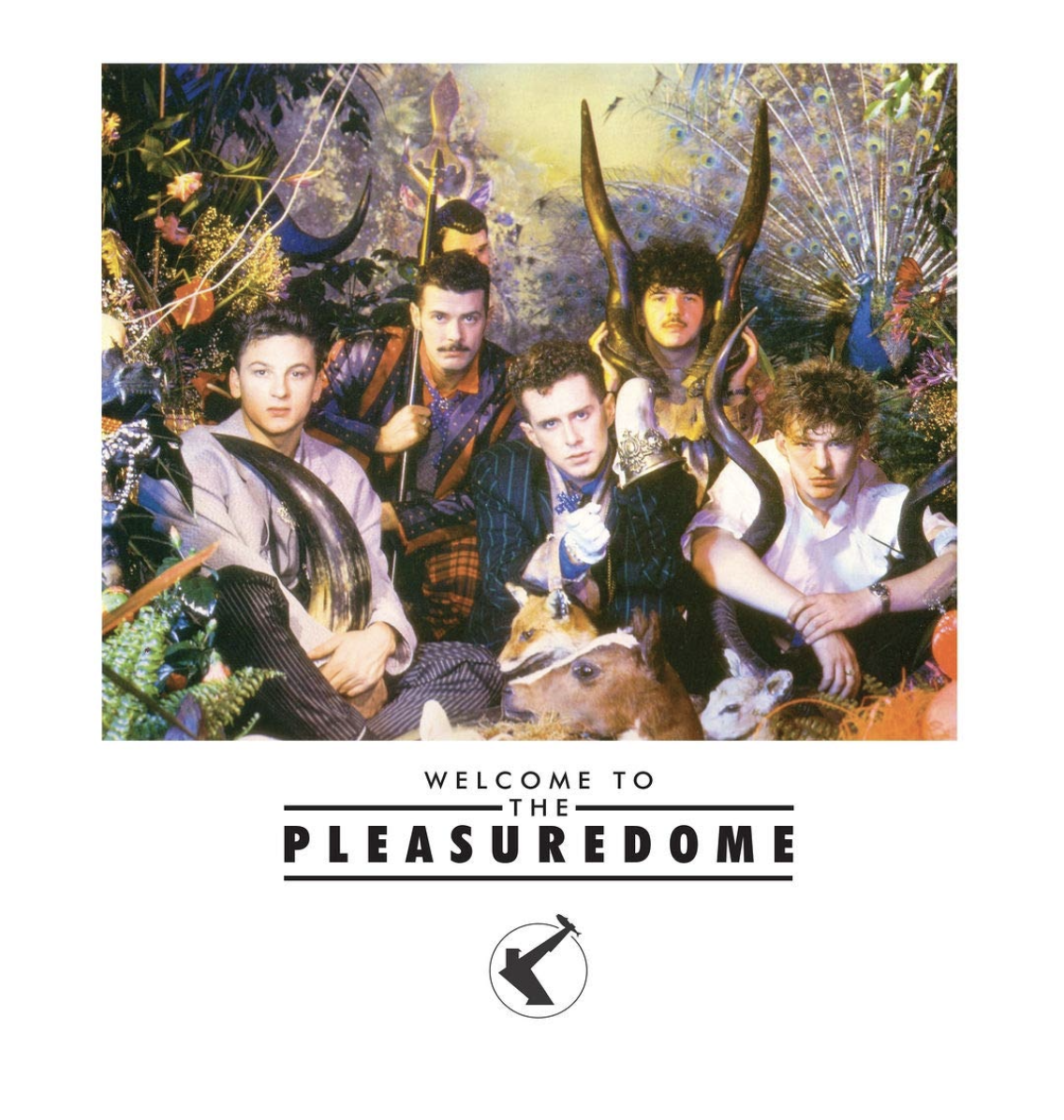

Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Welcome to the Pleasuredome

There are two things that I remember as most stunning and impactful about this album when it came out. One was the lush sound and the fresh thunder of their two hit singles, “Relax” and “Two Tribes” — two, generation-stamping anthems — and that the band was so obviously, emphatically, and (in 1984) courageously openly gay.

You couldn’t escape those songs in the fall and winter of ’84/’85. You heard them in restaurants and bars and clubs, cascading from ceilings and walls, and from chilly Manhattan’s few open windows when outside. “When two tribes go to warrrr…” stabbed at you. And that, to me, still, inexplicable lyric: “Relax, don’t do it, when you want to come” — surely you had to do something if you wanted to come?

The whole album is beautiful. Their cover of “San Jose (the way),” a Burt Bacarach masterpiece, is as clean a version as ever crossed any genre. They did “Born to Run.” And they in no way embarrassed themselves. We did a big article on them in the first issue of SPIN, which, oddly, people were surprised by. I still love that record.

Bronski Beat, The Age of Consent

“Smalltown Boy” was one of the great, anthemic, and meaningful singles of the ’80s, and the first from this genre-melting, inventive debut album. The song is about a gay man leaving home for the big city and the accompanying video controversially has him trying to pick up a man at a swimming pool, getting beaten up by predictably disgusted hetero guys. It was the way things were for gay men in the mid-1980s, but no one else was singing about it, in aching falsetto on a haunting track.

The album was not a big hit, and they weren’t exactly a heavy-rotation act on MTV, also predictably. But I think it is one of the best albums of the last 40 years, stunningly gorgeous and seamless musically, and far braver as social commentary than anything U2 ever did. The songs are ethereal and dramatic. One is a richly toned cover of “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” the Gershwin classic immortalized in the 1935 musical Porgy and Bess. “Why?” is another chilling anti-homophobia tale, and “I Feel Love/Johnny Remember Me” is a glorious mash up of Donna Summer and ‘60s hitmaker John Leyton.

Daniel Kohn, SVP Artist Relations and Music

Bruce Springsteen, Born in the U.S.A.

In 12 bombastic, incredibly accessible songs, Springsteen transformed here from a critically acclaimed arena rocker into an international household name. The music on the follow-up to the sparse Nebraska was so omnipresent that it often overshadowed the lyrics, which addressed deeper subjects such as the struggles of the working-class and the meaning of patriotism and duty. Beginning with the title track, which criticized the government’s treatment of veterans, but was inevitably misinterpreted as a jingoistic anthem, Born spawned seven singles, all of which hit the Top 10 in the U.S., and captured the pop culture zeitgeist like few other albums of its time.

Madonna, Like a Virgin

Madonna moved from Michigan to Manhattan with visions of grandeur, and thanks to her relentless work ethic, magnetic energy, and danceable pop songs, finally dented the mainstream in 1983 with her self-titled debut. The following year’s Nile Rodgers-produced Like a Virgin made even more of a splash, blasting her into another stratosphere thanks to irresistible earworms such as the title track and “Material Girl” – both of which are still radio staples 40 years later. The album also sports the favorites “Dress You Up” and “Angel,” and even a cover of Rose Royce’s 1978 hit “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore.” Within months, Madonna was the It Artist in pop music. Decades of dominance would follow.

Metallica, Ride the Lightning

If 1983’s Kill ‘Em All was a statement of intent, Metallica ensured people could hear them loud on Ride the Lightning. The band’s first with bassist Cliff Burton moved away from straight thrash metal by blending acoustic guitars and vocal harmonies on a moving power ballad about suicide (“Fade to Black”), incorporating the best use of a bell this side of AC/DC (“For Whom the Bell Tolls”), and throwing in a critique of the criminal justice system (the title track). Ride the Lightning is a crucial bridge to 1986’s Master of Puppets, which many consider Metallica’s finest hour.

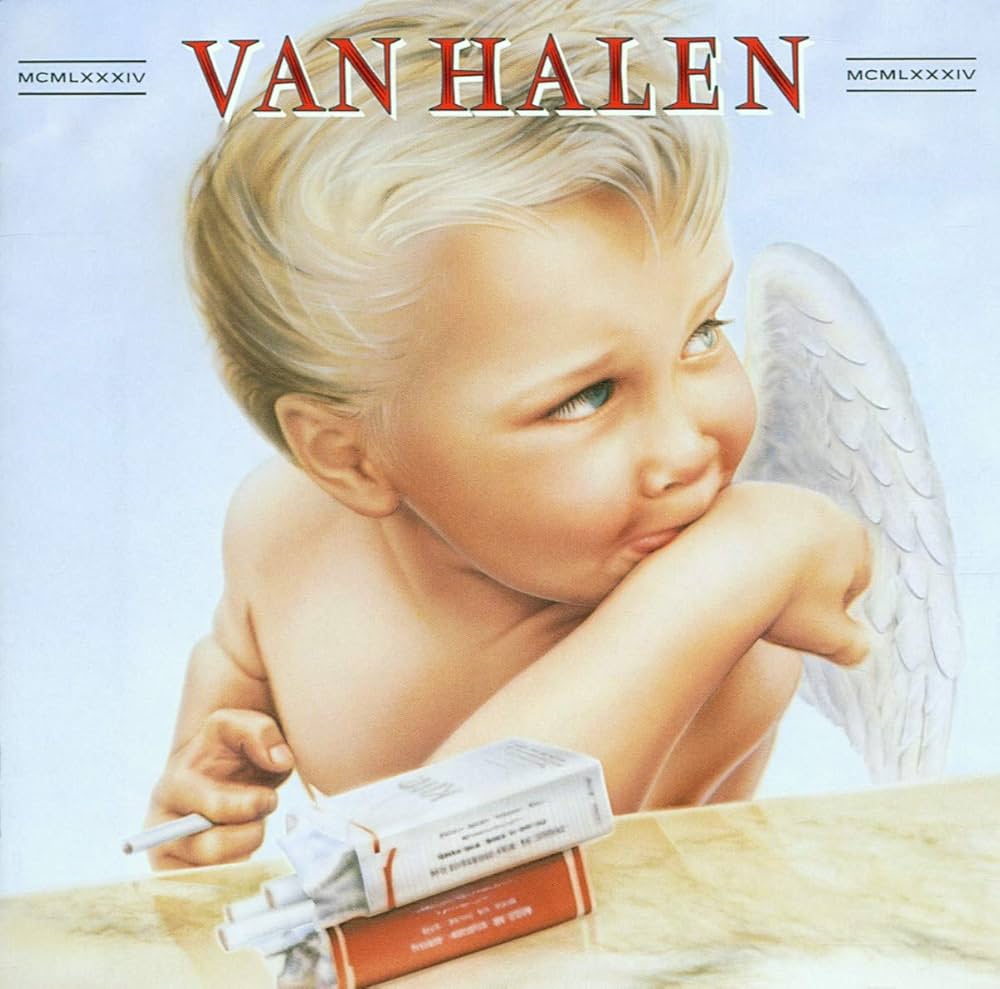

Van Halen, 1984

The final salvo of the David Lee Roth-fronted Van Halen until 2012 (Roth reunited with the band in 2007), 1984 is undoubtedly among the most beloved mainstream rock albums of all time. One of the reasons? The controversial but unabashed use of synthesizers, which hooked new fans and drove “Jump” to five weeks at No. 1. Keyboards also drive the power mid-tempo “I’ll Wait,” but Van Halen never abandon their core, hard rockin’ sound on killer tracks such as “Panama,” “Hot for Teacher,” and “Top Jimmy,” which finds guitarist Eddie Van Halen at the top of his game. Roth was gone by the following year, but 1984’s shadow remains long: Try going to a sporting event without hearing “Jump” at least once.

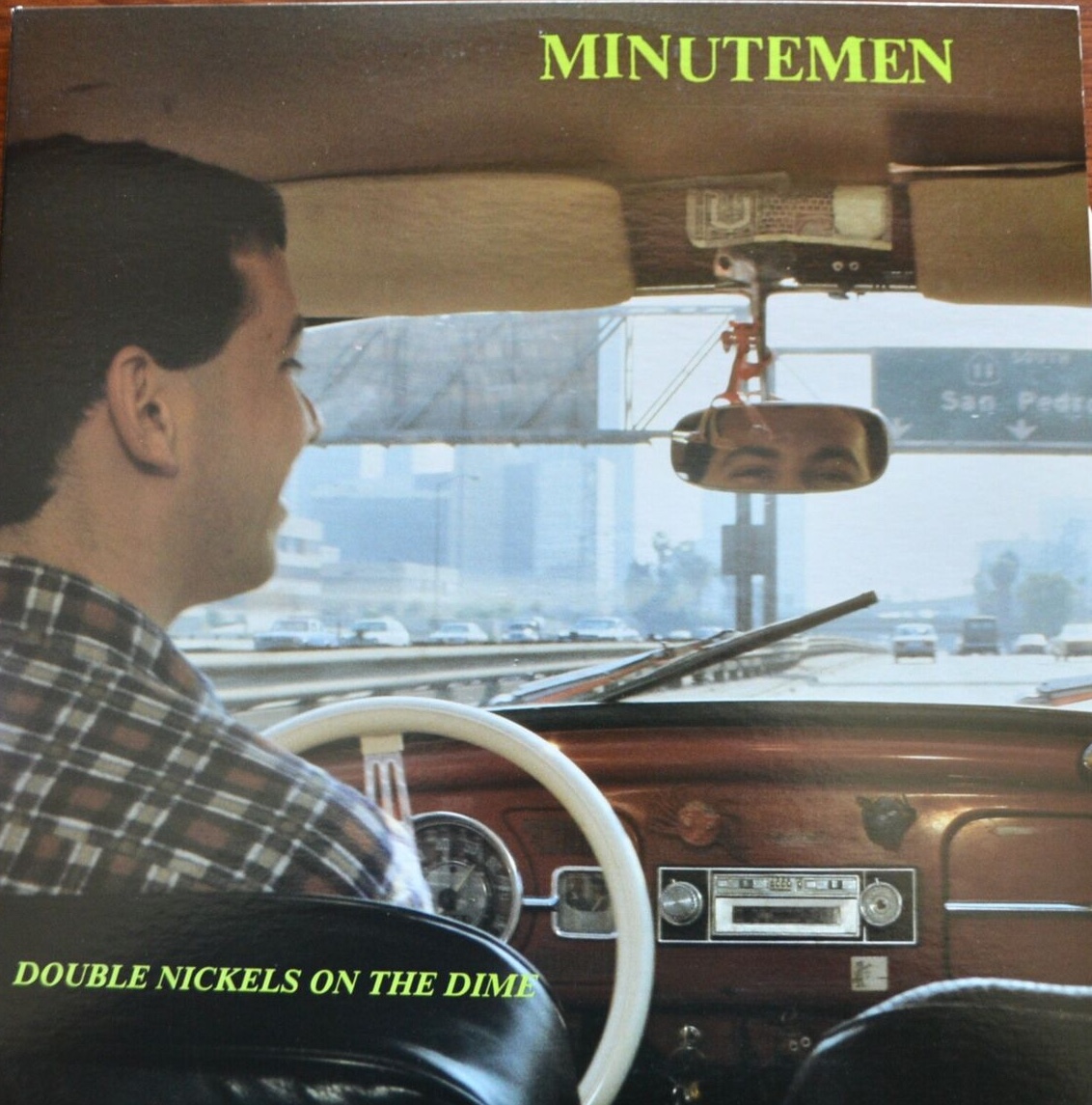

Minutemen, Double Nickels on the Dime

In just over 80 minutes, Minutemen changed punk forever. Across a whopping 45 songs, Double Nickels on the Dime (the title is a dig at Sammy Hagar’s contemporaneous “I Can’t Drive 55”) ditches hardcore for a radical blend of rock, funk, jazz, country, and spoken word, with wry lyrical matter ranging from working-class realities to Vietnam. Largely owing to the fact that the trio were raised in San Pedro, Ca., far enough away from the more restrictive L.A. punk scene, Minutemen brought forward a refreshing reinterpretation of the genre in a way only outsiders can. The band were cut short the following year when guitarist D. Boon died in a van accident, but their influence remains felt. Jam econo indeed.

Jonathan Cohen, News Editor

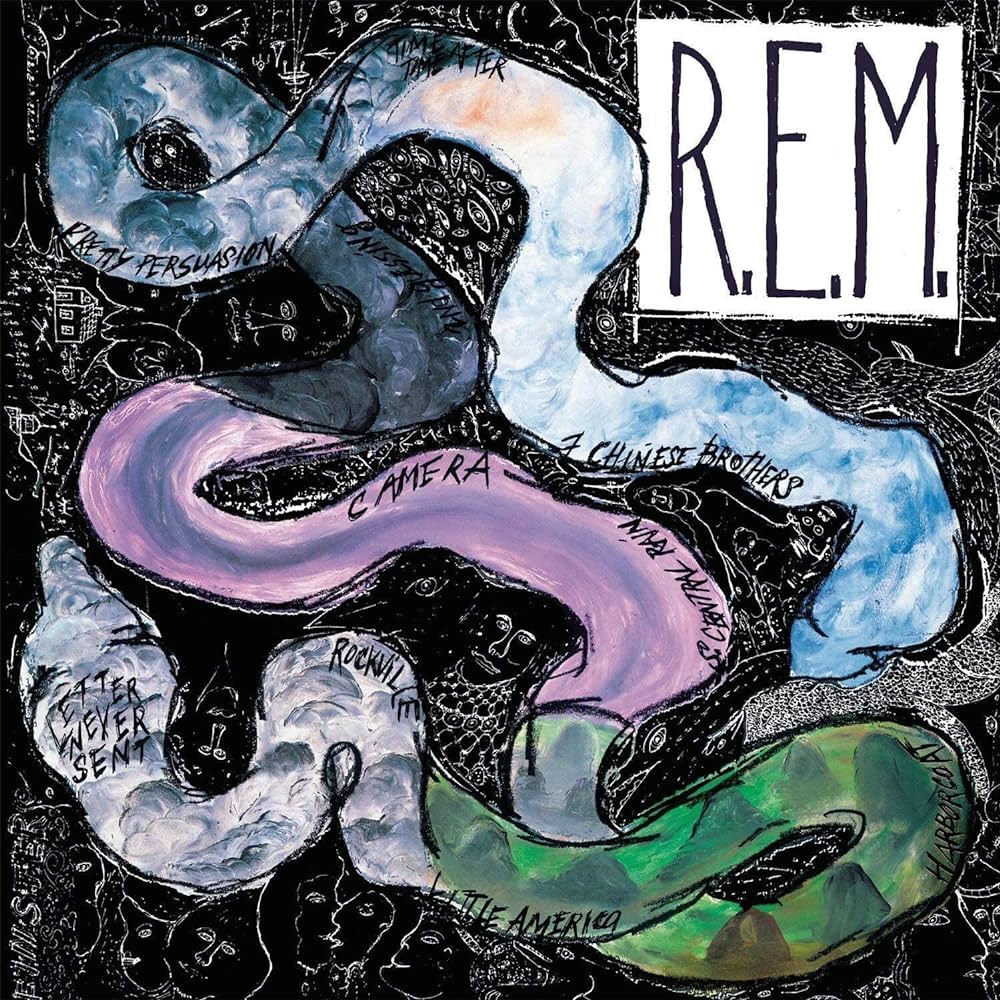

R.E.M., Reckoning

Who could envy these Georgia upstarts having to quickly follow up the prior year’s Murmur, one of the best debut rock albums of all time? The solution was to make Michael Stipe and company sound as live as they did in local clubs, and just keep writing great songs. They’re in plentiful supply on Reckoning, from nimble rockers such as “Harborcoat” and “So. Central Rain” (cue “I’m sorry” chorus chant…) to the Velvets-y ballad “Time After Time (Annelise),” the warts-and-all elegy for a dead friend “Camera,” and the Mike Mills-written, country-flavored goof “Don’t Go Back to Rockville.” R.E.M.’s subsequent ‘80s albums became increasingly layered, produced, and commercially successful, making Reckoning one of the final definitive documents of the band’s more unpolished early essence.

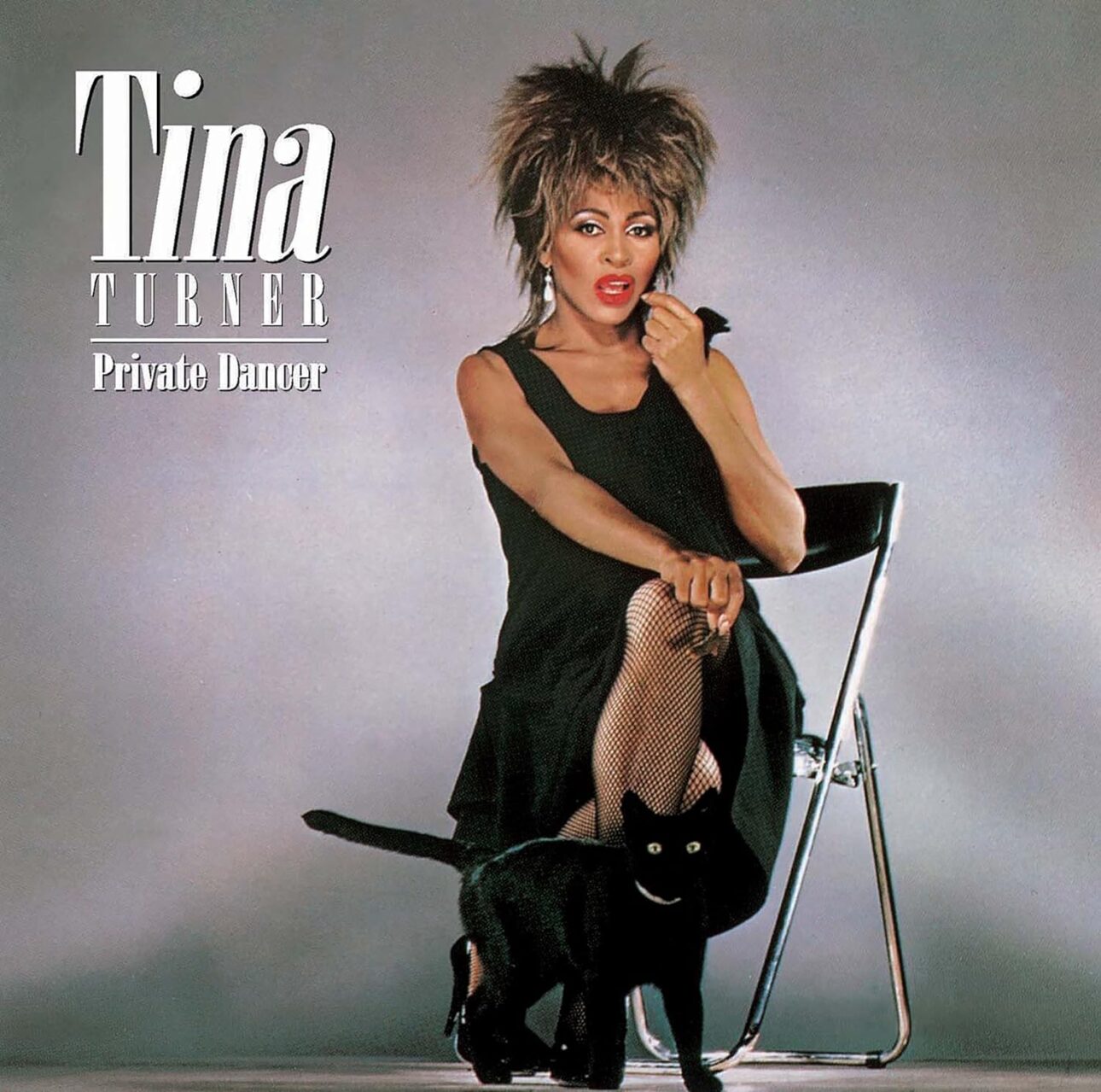

Tina Turner, Private Dancer

Turner staged one of the most improbable comebacks in music history at age 44 with Private Dancer, which has since sold 12 million copies worldwide. The blinding sheen of the oh-so-’80s production notwithstanding, the album finds Turner in commanding voice on all-timers such as the power ballad “What’s Love Got to Do With It” (dig that synth masquerading as a harmonica), the sultry title track, and the triumphant “Better Be Good to Me.” Throw in some David Bowie, Al Green, and Ann Peebles covers and a couple of Jeff Beck guitar solos, and you’ve got an album that could only have existed in this time and place. Even better: Turner became the oldest woman to ever top the Billboard Hot 100 with “What’s Love,” a feat that stood for 15 years.

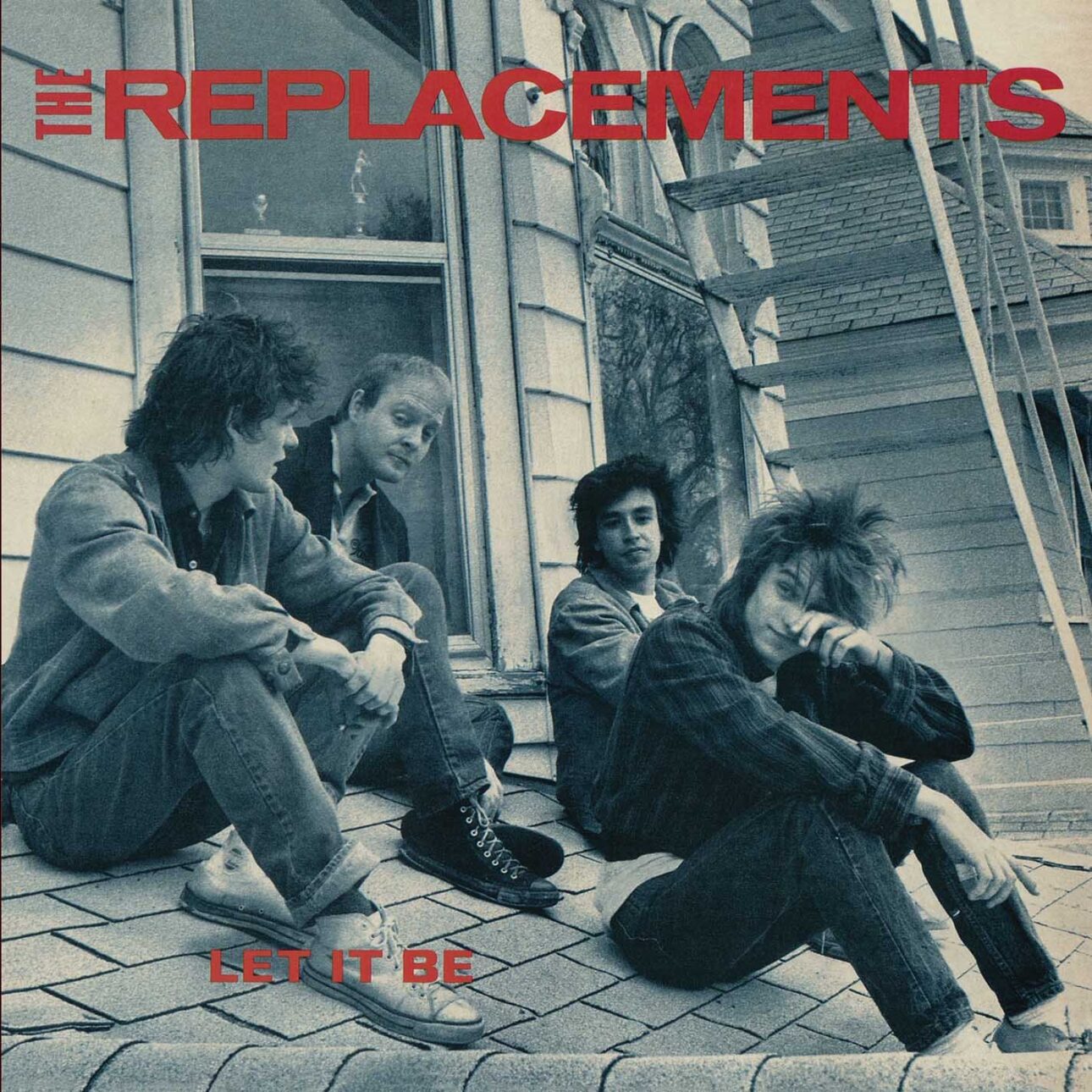

The Replacements, Let It Be

Like suddenly watching your television switch for the first time from black and white to color, everything’s an order of magnitude more vibrant, catchy, and soul-stirring from the first jaunty guitar lick of “I Will Dare” on the Replacements’ last indie album before signing with Sire. Paul Westerberg’s writing takes giant leaps for rock’n’roll-kind here, and he’s no longer singing or screaming at you, but to you. As further demonstrated by its iconic rooftop-shot album cover, Let It Be burbles with an honest ambivalence that’s never far from the surface: “We’re Comin Out” is unhinged punk superglued to something snazzy and finger-snapping, the slithering and shimmying “Favorite Thing” couches affection in impermanence (“you’re my favorite thing / once in a while”), and a faithful cover of Kiss’ “Black Diamond” thumbs its coke-encrusted nose at safety pin-pierced rockers who normally wouldn’t be caught dead listening to those face-painted, fire-breathing multi-millionaires.

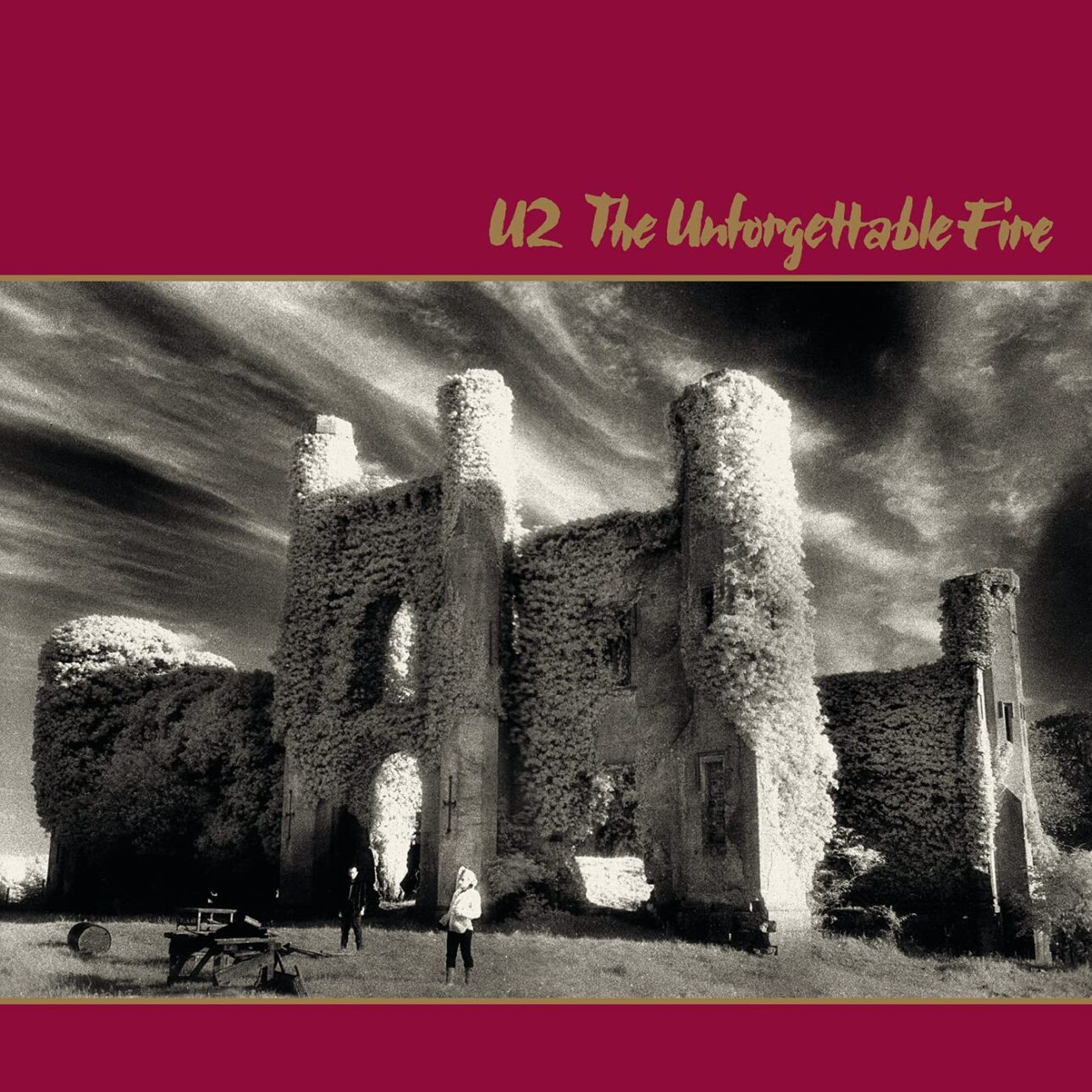

U2, The Unforgettable Fire

Concerned they’d be pigeonholed as just another arena rock band after 1983’s War, U2 went back to the drawing board with producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois on The Unforgettable Fire, forever transforming their sound into the deeply felt, widescreen music that persists to this day. Sure, “Pride (In the Name of Love)” and “Bad” are tailor-made for stadiums, but the beautifully sung title cut, the hymn-like “MLK,” and the proto-”Where the Streets Have No Name” opener “A Sort of Homecoming” benefit greatly from the arty nuances of the production and U2’s willingness to leapfrog the norm. Throughout, Bono proves to be a peerless tour guide of emotion, experience, and understanding, be it chronicling U.S. political assassinations, the difficulty in reconciling rock’n’roll with religion, or the perils of drugs.

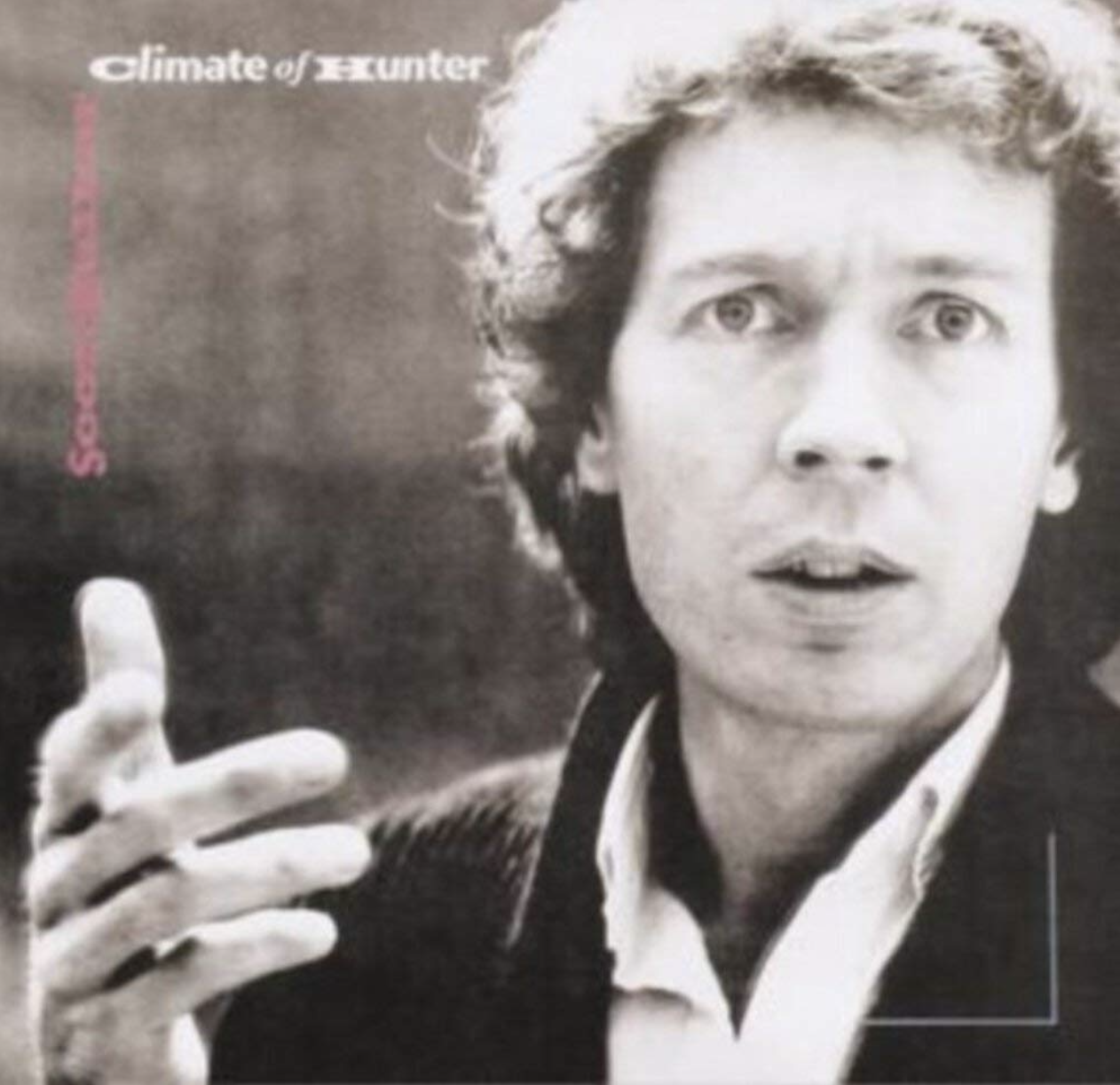

Scott Walker, Climate of Hunter

If you’d not heard Walker since his ‘60s salad days as a teen idol and eventual AM radio staple, you were surely befuddled by Climate of Hunter, his first under his own name in a decade and six years following his swan song with the Walker Brothers, Nite Flights. That record’s left-field embrace of Bowie-in-Berlin art rock provides at least a partial roadmap to Climate, one of the more exquisitely strange albums ever released by a major label. The ominous “Track 3” is propelled by an insistent beat and Ray Russell’s Fripp-ian guitar solo, while Mark Knoplfer turns up for some reason to play acoustic on “Blanket Roll Blues” (the only song ever co-written by, umm, Tennessee Williams). In between are pieces that stretch the definition of what a song even is, an idea Walker would push to incomprehensible extremes in his later work.

Liza Lentini, Executive Editor

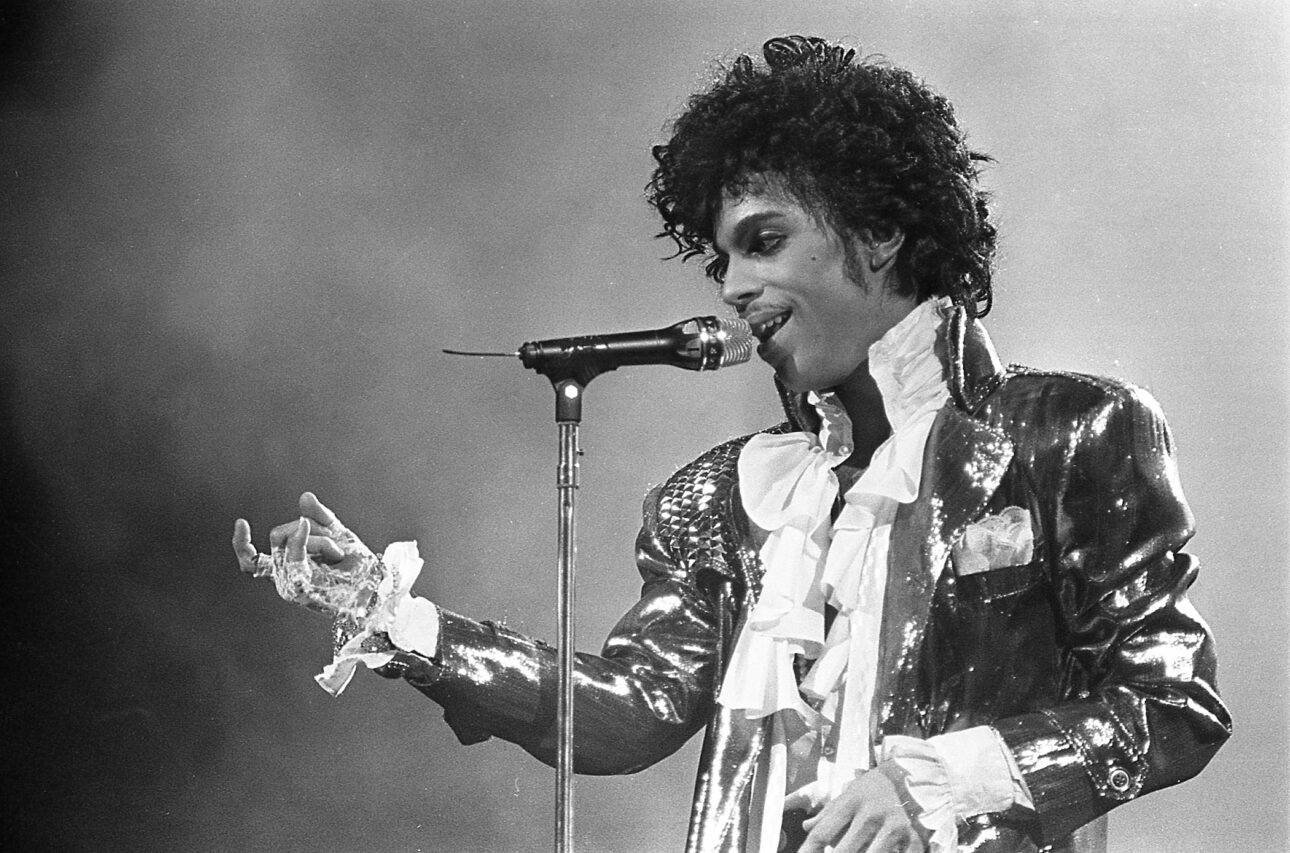

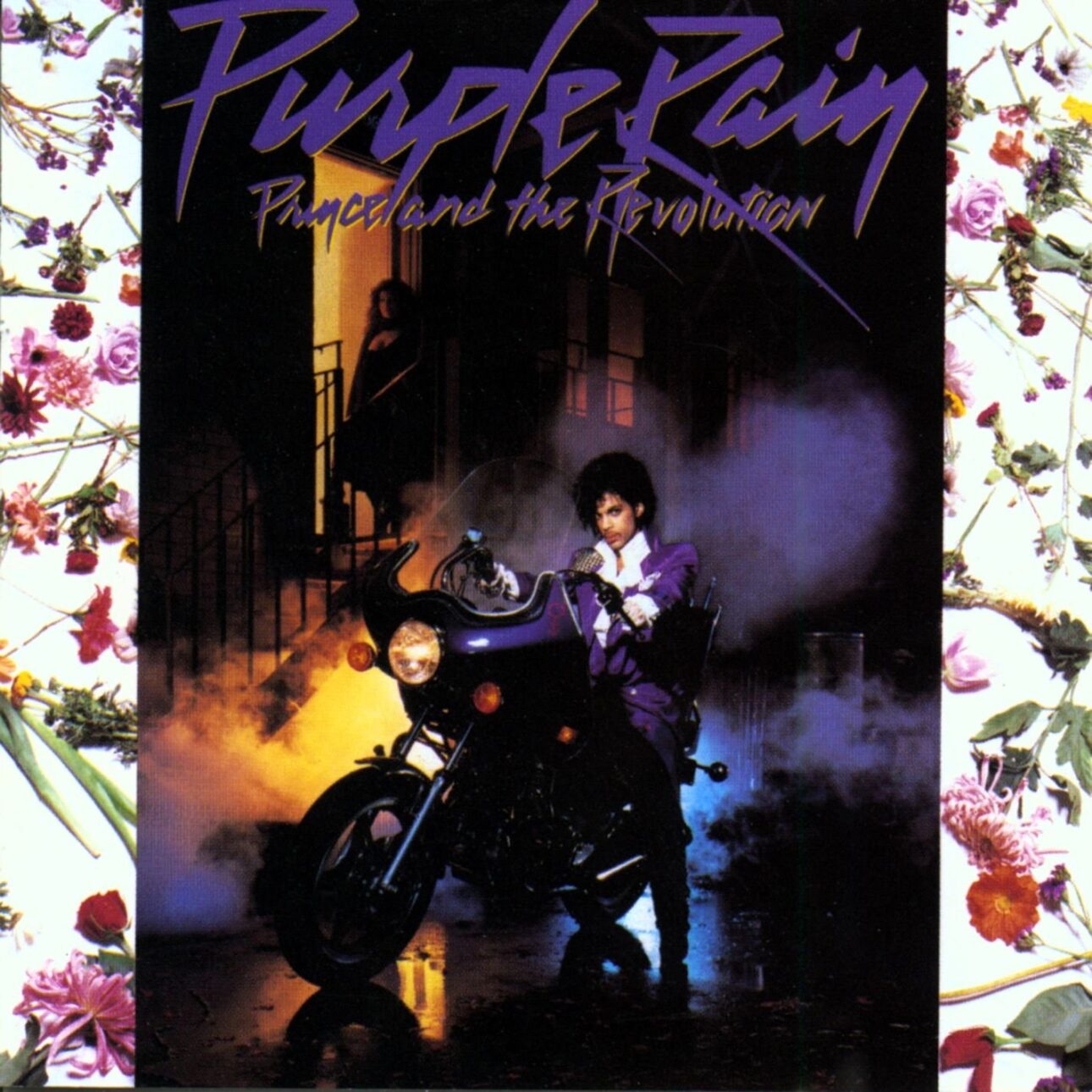

Prince and the Revolution, Purple Rain

It wasn’t enough for Prince to have the No. 1 Song of the Year with “When Doves Cry,” according to the Billboard Hot 100 (“Let’s Go Crazy” also hit No. 1 that year), but he also won an Academy Award for Best Original Song Score. The album has since gone 13x platinum and is technically the soundtrack to the critically acclaimed, semi-autobiographical hit film.

It’s safe to say, the artist then still formally known as Prince – forever to be known as one of the greatest geniuses in music — ruled 1984 with a purple crown. And if all that wasn’t enough, thank the album’s fifth track, “Darling Nikki,” for launching one of the most critical battles in rock history — the PMRC Senate censorship hearings, where musicians like Frank Zappa and Dee Snider famously defended free speech. So you can thank Prince and “Darling Nikki” for Parental Advisory stickers, letting everyone know exactly where to find the best music.

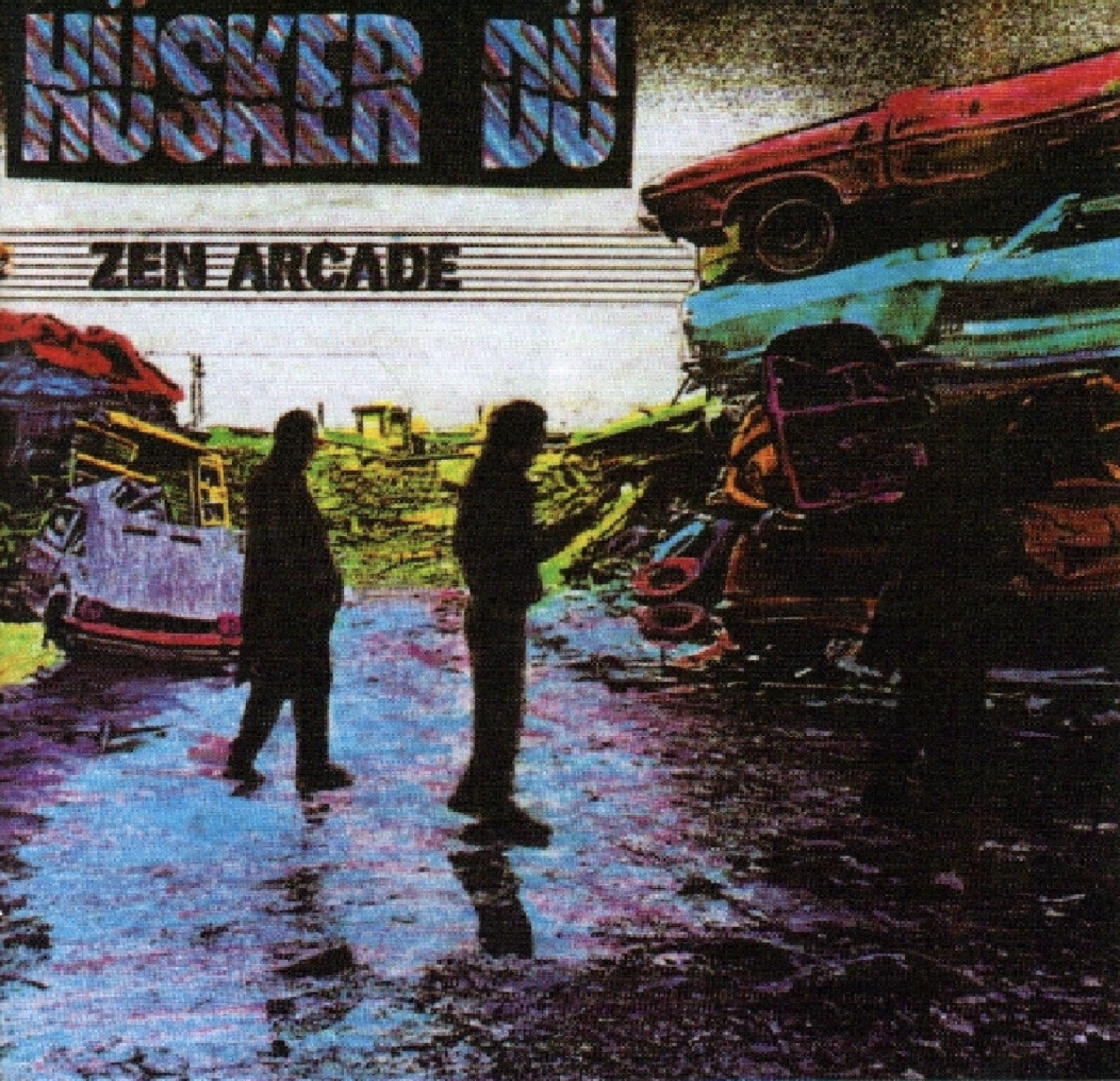

Hüsker Dü, Zen Arcade

It’s so satisfying observing younger generations discover Zen Arcade for the first time, their reaction appropriately completely visceral. Those who get it really get it. It was the same for us upon its release in 1984, the band’s second album, considered by some their best and most emotive, a dissection that’s arbitrary when speaking of their six-record catalog — all released in under 10 years — each a diamond of varied cut, color, and clarity.

Hüsker Dü should be required study for absolutely any young musician of any genre, the everlasting message being: If you’re true to your unique talent and sound you can create something far greater than chart success, you can create something that comes deep enough from your soul to change the face of music forever.

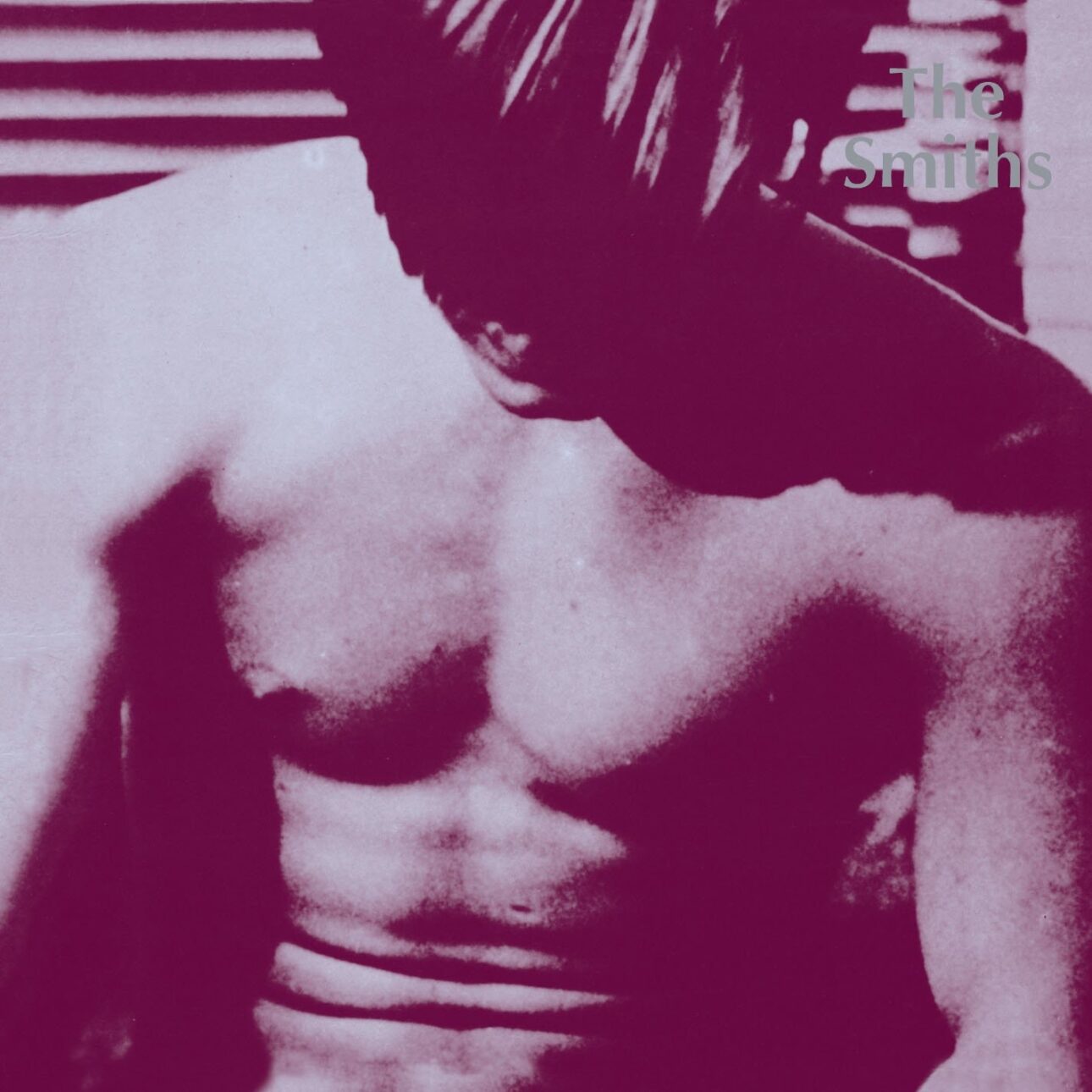

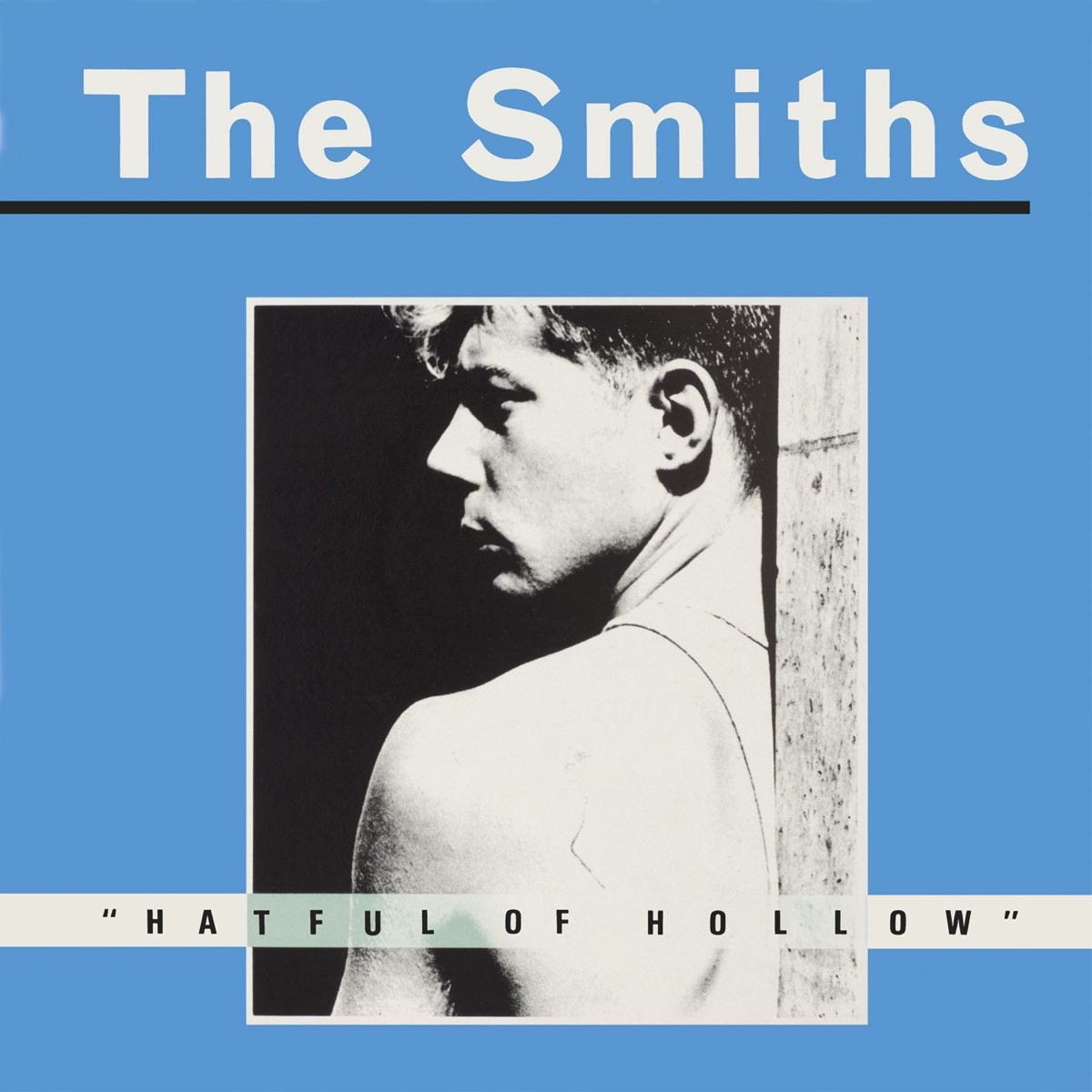

The Smiths, The Smiths / Hatful of Hollow

The only thing better than the Smiths’ eponymous debut album (released in February 1984, undoubtedly one of the best of the ‘80s) was the band’s compilation release, Hatful of Hollow, at the end of the year. Not “better” because it was a better record, but with Hatful’s BBC 1 Sessions November release, the Manchester four-piece gave us two albums in one year, quite a gift from a band that only lasted five years.

Aside from uniquely executed, strikingly powerful, beautiful-melancholic songs, the Smiths gave us a place to put our ennui — turning the mirror on the upbeat sadness of our deepest humanity. From the former’s “What Difference Does It Make?” to the latter’s “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now,” we would never be the same.

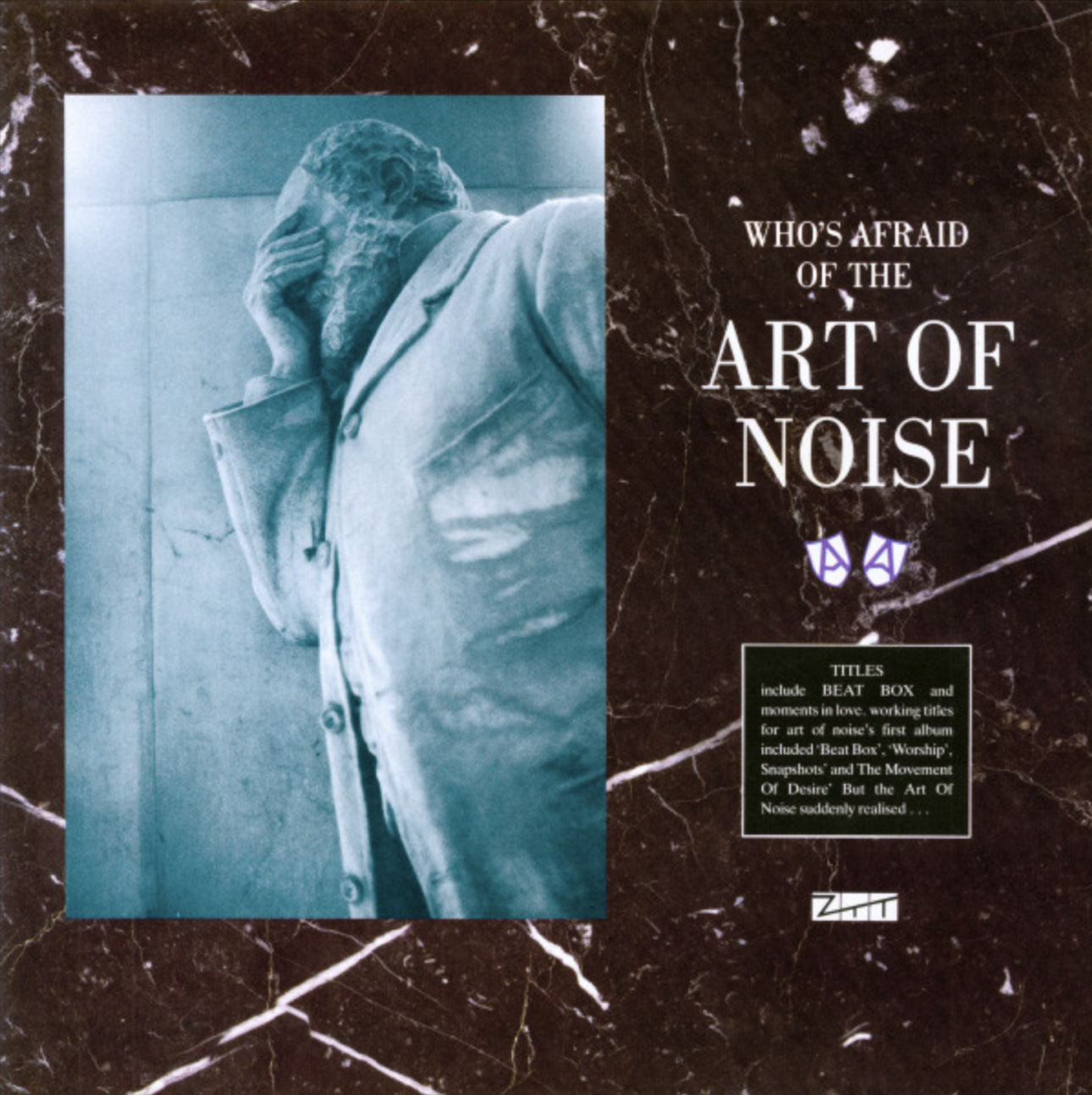

Art of Noise, Who’s Afraid of the Art of Noise?

Read through this list of incredible albums and then come back to this one. Only then will you truly understand the startling improbability of the album’s almost entirely instrumental fourth track, “Close (To the Edit),” reaching the U.K. Top 10, as well as its iconic music video (featuring a punked-out little girl destroying musical instruments on train tracks) taking home two MTV Music Video Awards the following year.

In the middle of Reagan-era ‘80s, Art of Noise made avant-garde somewhat mainstream — and without becoming sell-outs.

If you love synth-pop, take a moment to thank Art of Noise for their true revolutionary spirit during their short, seven-year stint as a band. Nothing about their success made sense — they made it make sense. They’re high on the list of band’s I wish would magically reunite and make more music.

Matthew Thompson, Senior Editor

Cabaret Voltaire, Micro-Phonies

Ten lifetimes ago in the Australian then-industrial city of Newcastle, my college mates and I frequented a usually empty nightclub for its dollar drinks and its imaginative, well-stocked, and well-cranked DJ who was dying of AIDS (as we wrenchingly learned when he abruptly died) and had no one to please but us. It turned out we shared a zeal for the juddering angularity and stimulatory strangeness of Dadaist electro-and-tape masters Cabaret Voltaire. Micro-Phonies of 1984 is a twitching puzzle of danceable paranoia, the Sheffield maestros’ first with Virgin distribution, and known to aficionados for containing two stripped-back songs that were fused into the glorious 12” single, “Sensoria.” If other punters happened to be at the club in Newcastle when our man let rip with this sonic genius, they’d often stomp off the floor yelling: “No one can dance to this shit!” Leaving just us to soar, to undulate, to work through the Cabs’ puzzles of sound and mind.

Hunters & Collectors, The Jaws of Life

This sweaty onslaught of walk-right-fucking-over-you basslines, steel-jangle guitar, beer-jungle percussion, and the throaty, sexually-charged, blue-collar lyricism of Mark Seymour was conceived flying down the autobahn. That’s according to Seymour, who says it was on the road in Germany in ‘83 that the Hunters & Collectors decided to stop being artistically pretentious and write a simple, direct body of songs to tour. Personally I reckon their pretentious era was the best, but a man’s gotta make a living, and this album, with stunning gems like “The Slab” (Shriekback meets Aussie pub rock), is a strong bridge between their avant garde past and the sentimental crowd-pleasers they would become.

Eurythmics, 1984 (For the Love of Big Brother)

Ever catch Nineteen Eighty-Four, the underwhelming, by-the-numbers, yawningly faithful 1984 movie adaptation of George Orwell’s novel of the same name? Starring Richard Burton, John Hurt, and Suzanna Hamilton, the flick was much anticipated ahead of its release, but then largely forgotten. Alan Parker’s Pink Floyd — The Wall from two years prior also boasted big tableaux of mass hate, but those had a visceral potency in comparison to the dated feel of equivalent scenes and much else in Nineteen Eighty-Four—much else except for the Eurythmics’ often sparkling, surprising soundtrack. Director Michael Radford hated it, mind you, having a big tantie over the matter and switching it for orchestral movie music on his equally-who-cares director’s cut. But fuck me, if you want the mania of totalitarian power surging through you, turn the volume to police-raid levels and hit Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart letting rip with “Doubleplusgood.” Juicy goodness abounds, with other tunes still alive 40-years-on including “Sexcrime (Nineteen Eighty-Four),” “Greetings From a Dead Man,” and “I Did It Just the Same.”

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, From Her to Eternity

Before Nick Cave became an eccentric vicar playing his humble part in bringing the Good News to the masses, he was a degenerate asshole. That Cave was better. That Cave made thrilling, volcanic music, instead of music that people keep telling me is actually quite good. That Cave made songs like the title track of this—his first album after the collapse of the spectacularly fucked-up Birthday Party. Rather than being a saintly reflection upon the toll of such base emotions as obsession, “From Her to Eternity” is obsession. Better would it have been had the vicar never been born.

Simple Minds, Sparkle in the Rain

I fucking hate it when bands I love go stadium and all of a sudden every asshole is into them. Sure, Dire Straits got fatly rich when they de-nuanced their storytelling from the likes of “Sultans of Swing” to the thermonuclear radio-friendly rock joy of “Money for Nothing,” but nobody asked me, and like I got a dime from their selling out. Sparkle in the Rain is what happens when the Lou Reed/VU-influenced Scottish New Wave band responsible for such striking pop as “Love Song” and “The American” go all arena on me. Motherfuckers—I want to hate this album with its shimmering bigtime strut, produced as it was by shiny Steve Lillywhite (who did U2’s Boy and went on to do the first three studio albums of the Dave Matthews Band). I really want to hate it. But then, just as I did as a kid 40 years ago, I play it anyway—and the beauty and angular turns of a track like “Up on the Catwalk” exert just enough force to hold the band’s growing sentimentality at bay, and I’m transported. Although I’m still not sure what to make of Jim Kerr and the lads covering Lou Reed’s “Street Hassle,”

Ryan Reed, Senior Editor

Talk Talk, It’s My Life

On their charming if unoriginal debut, 1982’s The Party’s Over, Talk Talk came across as New Romantic trend-chasers. But everything clicked with the band’s brainier and more ambitious follow-up, which moved into atmospheric territory (the sparse, spine-tingling “Renée”) while maintaining their synth-pop finesse (the eternal “Such a Shame” and “It’s My Life”).

Talking Heads, Stop Making Sense

Even removed from the carefully coordinated visual spectacle of Jonathan Demme’s concert doc (the musicians’ lockstep stage entrances, David Byrne dancing with a lamp and donning his signature “big suit”), Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense remains one of rock’s essential live documents. Everything on the soundtrack is jolted with electricity, from the art-funk avalanche of “Making Flippy Floppy” to the euphoric arms-raised drama of Byrne’s solo cut “What a Day That Was.”

King Crimson, Three of a Perfect Pair

King Crimson, reactivated for the New Wave era, made three jarringly innovative LPs—weaving Adrian Belew’s velvety vocals into a fabric of Frippertronic experiments and interlocking gamelan guitars. The trilogy ended with Three of a Perfect Pair, which, per longtime leader Robert Fripp, split their “accessible” and “excessive” vibes onto sides A and B, respectively. It’s an odd but intriguing choice, highlighting both extremes of their sound: Belew’s hooks were never stickier than on “Sleepless” and the title track, but Crimson never sounded more nightmarish than amid the industrial clang of “Dig Me.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.