Last summer, Coldplay hit headlines around the world when they announced that their 10th album, Moon Music, would be pressed onto vinyl derived from no less than nine recycled plastic bottles. The result, the band claimed, would reduce carbon emissions by some 85% and avoid the creation of 25 metric tonnes of virgin plastic.

More from Spin:

Dear Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: Induct Tracy Chapman Already!

Festival of the Year: Ultra Music Festival

The Night Porto Out-Partied Lou Reed (and the Infamous 1980 Concert That Never Happened)

In June, they announced that for their latest world tour they’d reduced their carbon footprint by an estimated stunning 59%, compared to their last global tour. And they weren’t alone. In May, Billie Eilish declared that her third album, Hit Me Hard and Soft, would be pressed onto recycled or eco-vinyl, with the record’s packaging also derived from recycled materials.

Appropriately enough, given that Eilish is essentially a spokesperson for Gen Z, who’ve been dubbed “the sustainability generation,” she explained that the matter had always been close to her heart. “My parents have always kept me well informed and hyper-aware that every choice we make and every action we take has an impact somewhere or on someone, good or bad, and that has always stuck with me,” she told Billboard. “I can’t just ignore what I know and go about my business and career and not do something.”

For Craig Evans, CEO of the UK-based Blood Records, a company that specializes in limited-edition vinyl (and found online infamy earlier this year with a Saltburn soundtrack record filled with what the tabloids tactfully dubbed “cloudy bathwater”), Coldplay’s move is monumental.

“To be able to take plastic bottles—which we all know are a scourge on the environment— and be able to turn them into something, to me, is a Holy Grail thing,” he tells SPIN. “It’s like, ‘Wow! If, as an industry, we are taking a product that’s littering the oceans and turning them into something, that’s a fantastic place to be.”

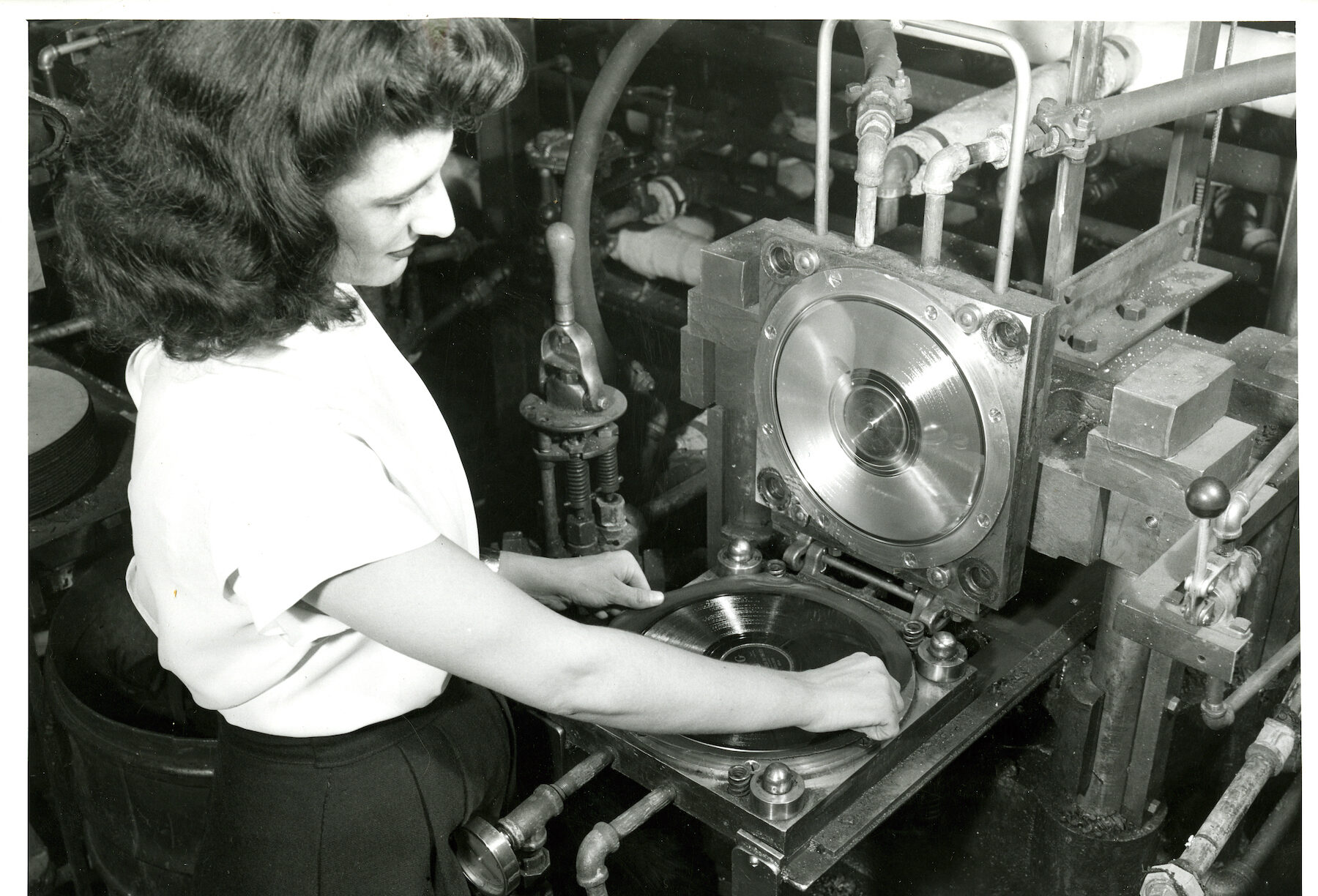

Nearly 50 million vinyl records were sold in the US last year — up 14.2% from 2022. Globally, vinyl records are estimated to account for around 30,000 tonnes of PVC (synthetic plastic) – which Greenpeace describeS as “the most environmentally damaging plastic” — every year.

The ongoing vinyl revival, which was perhaps truly minted in 2017, when Sony Music announced it would begin producing vinyl records for the first time since 1989, has been fantastic for music fans and musicians alike. But it comes at a cost. As Father John Misty suggested in the song “Now I’m Learning to Love the War”: “Try not to think so much about / The truly staggering amount of oil that it takes to make a record.”

Progress is certainly being made, but without speaking to every label and vinyl manufacturer on the planet, it’s hard to get a picture of how much progress is being made. Because there is no official means of measurement in place. On a similar note, all vinyl can technically be recycled in that it can be “reground,” says Evans, “but there’s no real infrastructure to do that. The bottom line is: We don’t really have a method or a means of doing that at the moment.”

The good news, he adds, is that numerous PVC alternatives are currently “coming to market in quick succession.” Bio vinyl, for example, reduces a record’s toxicity by replacing the petroleum in PVC with biogenic waste (substances such as cooking oil); the result can be 30 to 40% cleaner than the norm. A Dutch firm, Green Vinyl, meanwhile, uses “an injection molding system,” explains Evans, “which reduces the amount of energy or heat that’s needed in the pressing”.

Much of this is down to musicians exerting their influence on an industry that has been slow to act around environmental issues. “Artists at all levels have tremendous influence over their fans,” says Lara Seaver, Director of Sustainable Touring and Projects at REVERB, the Portland, Maine-based organization that advises Eilish on environmental matters and helped to make the vinyl of her 2021 album Happier Than Ever more sustainable.

“An artist at [her] level is able to have an influence over not only conversation, but also action within the music industry and beyond,” she continues. “Choosing to wield this power for the environment and our collective future is a game-changer.”

Evolution Music, an independent music media company based on the U.K.’s southeast coast, encompasses a record label, Roulette Records, and a radio station and record store that both go by the name Deal Radio. Given that this is a small enterprise, it seems extraordinary that Evolution should be responsible for Evovinyl, which has been dubbed “the world’s first completely non-toxic and compostable bio-vinyl record”.

CEO and co-founder Marc Carey is reluctant to give away “the Kentucky Fried Chicken recipe,” but explains that the company replaces all that dastardly PVC with “sugarcane” or a similar “organic material.” Evolution’s first Evovinyl record is The Miner’s Son, a soundtrack album that accompanies the low-budget British drama of the same name. It took six years of trial and error for Evolution to produce the PVC alternative, and that record’s run was limited to 300 copies on blue vinyl.

Carey hopes that, with further research and development, Evolution will be in a position to bring Evovinyl to market. “We were initially thinking of this for our own use,” he says, “then over the last two years we’ve captured the attention of the industry and there’s a lot of interest, so the next big hurdle for us is about how we manage the scaling up of this globally.”

He teases three globally massive artists who are champing at the bit to get their hands on Evovinyl. This would be quite the coup for a company with such an independent spirit. Initially they were just happy to get Evovinyl through a pressing mashing; then came the question of what it actually sounded like.

Why, though, had this not been done before?

“That’s a big question,” says Carey. “My personal answer, having worked in fields of sustainability for the best part of 30 years now, is that the incentives just haven’t been there. It’s been business as usual and the music industry has got away with it for too long—and now it’s being held accountable. It’s ridiculous that, as a small independent label, when we went to the market to look for sustainable options, we couldn’t find a viable one. So we decided to create one for ourselves.”

Craig Evans tentatively agrees that the music industry hasn’t been particularly incentivized when it comes to eco-vinyl, since cleaning up usually comes with a price tag, though he acknowledges that records are often sold second-hand or donated to thrift stores rather than reaching landfill).

“Vinyl prices are at a record high,” he says. Indeed, they have outpaced inflation in the US due to supply chain issues, with the cost of a record having risen by 25.5% between 2017 and 2023. “You’ve then gotta find a way of tagging on more costs that will be passed on presumably to the consumer, which is a problem.”

He is, however, more forgiving about the lack of eco-friendliness across the industry, given how complex these matters are. This, he says, can lead to practises such as eco mixing— taking scraps of vinyl left over from the manufacturing process and reusing them for other records — being sold as more revolutionary than they actually are: “I work in this and I struggle to talk about it because it’s such a complicated subject.”

Evans proposes “an industry body that assesses the environmental impact and gives accreditation to a record, so that we build up a stamp that means something in the way that Fair Trade does.” This, he suggests, would reassure consumers and labels, and justify any necessary price hikes. In any case, he says, “if the consumer supports it, I think the industry doesn’t have a choice but to react to consumer demand.”

With Coldplay and Billie Eilish leading the charge, that demand does seem to be increasing. And with plastics companies currently in R&D with alternatives to PVC for records, Evans believes that the picture will look completely different in “eight to 10 years.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.