Joel Savoy doesn’t remember exactly when he first heard the music of Clifton Chenier, the King of Zydeco—the electrified and electrifying mix of Louisiana Creole music and hard-hitting blues—who was born 100 years ago June 25.

More from Spin:

Tropical Fuck Storm Batten Down the Hatches

A Decade of Feeling ‘Emotion’: Looking Back at Carly Rae Jepsen’s Most Underrated Album

Chaos and Control: The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of Liam and Noel Gallagher

“We grew up hearing Clifton’s music,” says Savoy of his childhood in Eunice, Louisiana, where his parents Marc and Ann are core forces in Cajun music and culture, something he and his siblings have taken up as well. “It was pretty much the only non-Cajun kind of music we heard in our household for a long time.”

Steve Berlin, the Los Lobos saxophonist, has a clearer idea. It was the mid-’70s after he’d moved from Philly to L.A. and was hanging out with brothers Dave and Phil Alvin, who he would soon join in the Blasters. Back then, Berlin would visit the Alvins at their Downey, California, home “staying up all night, drinking beer and listening to 45s until dawn.” Even in those boisterous sessions, Chenier’s accordion-forward blues and Louisiana French vocals made a big impression. Berlin remembers very clearly getting to see Chenier a few years later when he played at Verbum Dei Jesuit High School in South Central Los Angeles, as he did on several occasions.

“I grew up in Philly seeing Sun Ra,” Berlin says. “Those shows were epic, three or four hours long or longer. And at the end you wanted more. Clifton shows were very much in the same vein. Three, four hours, no breaks, no stops. And then the smell of red beans and everything, the whole milieu of all the expatriate Louisianans in a Compton high school gym. It was like leaving Earth for a little while. So that was my first live experience.”

And Steve Earle too. He’s pretty sure he first encountered Chenier’s music when in grade school in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and then again after he ran away from home to Houston at 14 in 1969, but it was a few years later while house-sitting for folklorist/archivist John Lomax III and had access to a vast record and film collection, that the music really made an impression. In particular, it was a 16-millimeter print of documentarian Les Blank’s 1973 film on Chenier, Hot Pepper, that hooked him.

“It’s about zydeco in general, but it’s mainly about Clifton,” he says. “So that’s when I became indoctrinated.”

Oh, and Mick Jagger? Yeah. Him, too.

“Clifton Chenier was a great influence on me,” he said in a 2020 interview with Far Out Magazine. “We first listened to him around 1965 when we went to the States.”

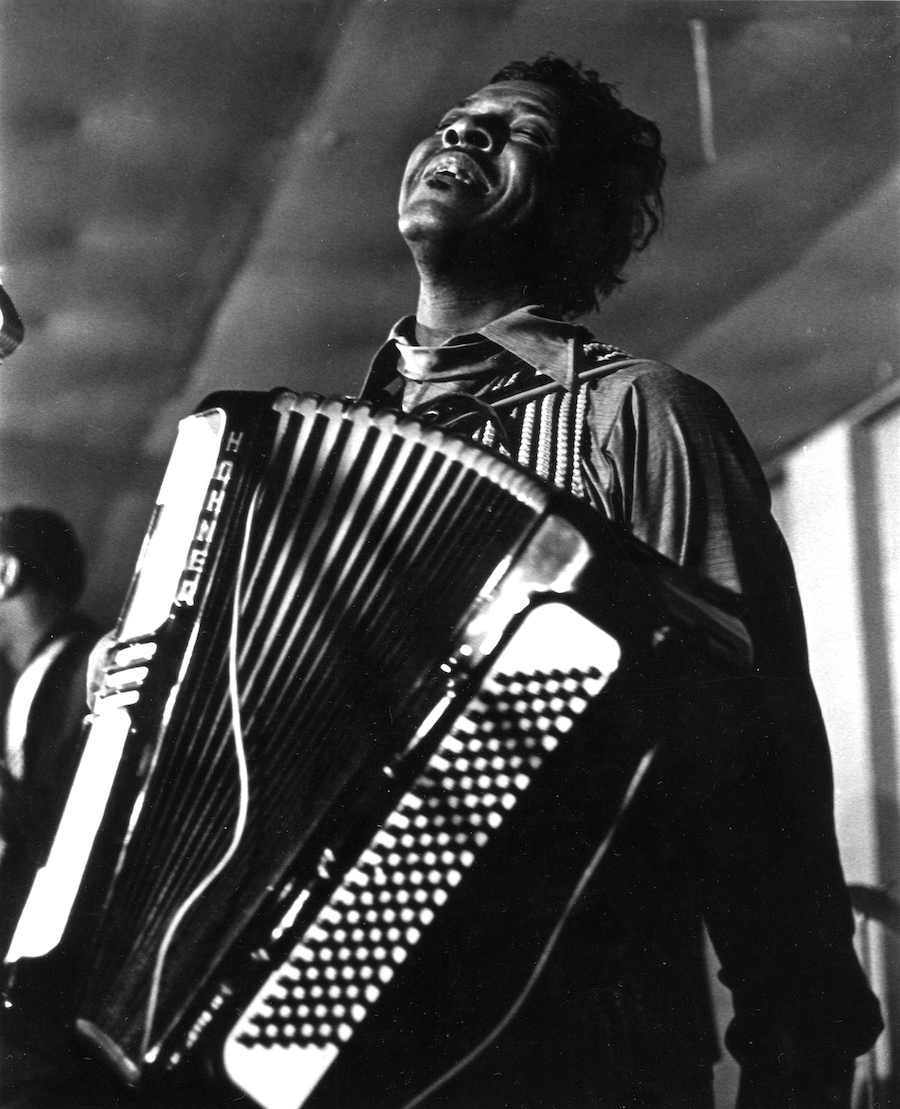

Hardly anyone outside of Louisiana and Texas had even heard of zydeco back then. But in a New York record shop, the cover of Chenier’s Louisiana Blues and Zydeco album caught Jagger’s eye, with its black and white photo of the musician, big smile on his face, playing a big piano accordion. Lawrence Welk it wasn’t, and Jagger could not resist.

But ask CJ Chenier about the first time he heard his father’s music, and he responds with a roiling laugh coming from deep in his belly.

“Oh man,” he says through his guffaws. “When I was first aware of what music was. Yeah! There you go.”

CJ is Clifton’s son, who joined his father’s band in the 1970s playing saxophone when he was in his 20s. He took over on accordion after Clifton died of complications from diabetes in December 1987.

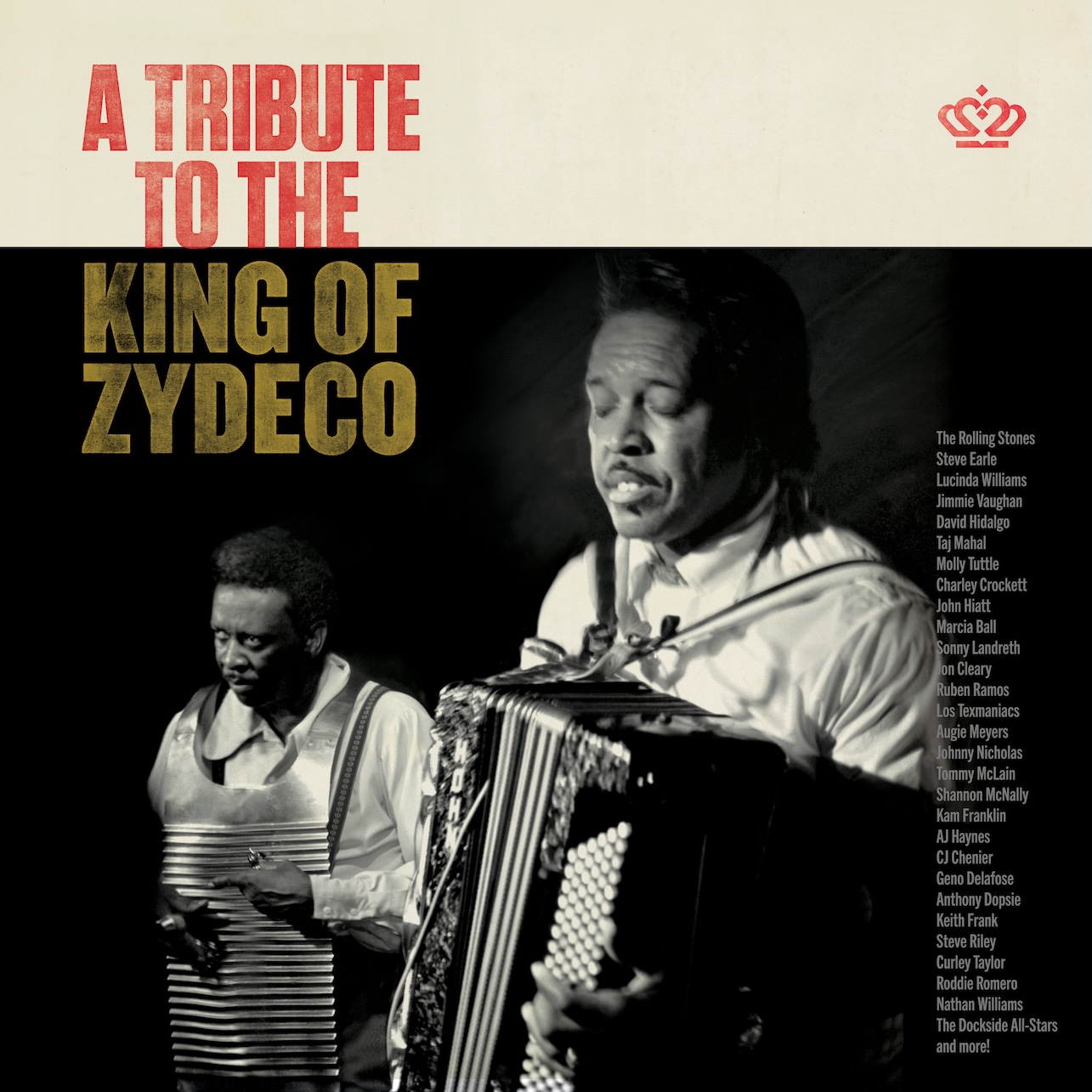

All of the people referenced here are involved in an album celebrating Clifton’s centennial birthday with a new album, Tribute to the King of Zydeco. Savoy and Berlin co-produced it, and it’s coming out on Savoy’s Valcour Records, based in his hometown of Eunice, just 15 miles from Chenier’s birthplace of Opelousas. Earle, CJ Chenier, and yup, the Rolling Stones are all featured performers, in a cast that also includes, among others, Lucinda Williams, Taj Mahal, Molly Tuttle, Charley Crocket, Los Lobos’ David Hidalgo, John Hiatt, Marcia Ball, Los Texmaniacs, and Jimmie Vaughan, mostly in collaborations with various musicians from the Southwest Louisiana region that birthed Clifton Chenier and zydeco.

The fact is, there wasn’t the latter without the former. Chenier gets credit for transforming the more rural sounds of the Black French Creole culture of that area—where descendents of Africans brought to Haiti in the slave trade took root alongside the white Cajuns, descended from the French people booted out nearly 300 years ago of what is now Nova Scotia.

But Chenier also named the musical style. Zydeco comes from his song “Zydeco Sont Pas Salés,” Creole French meaning “no salt in my snap beans”—les haricot being French for green bean, zydeco being a local dialectic variation.

That’s the song the Stones recorded for the album, the song that first entranced young Jagger and his bandmates back in the ’60s. Played by Chenier, it’s a frisky two-step, with Clifton’s brother Cleveland Chenier’s corrugated metal rubboard rattling throughout. Played by the Stones, it’s a red-hot rocker, arguably as smoking as anything the band has done in years. Maybe more so. It makes for a bracing opener to the album, setting the tone for a largely fierce, raw set of blues. Even the several ballads are raw and rough in the best ways.

Jagger, in fact, sings the song in very credible Creole French. From there it’s a fiery run through blues, swamp-boogie, and jump-jive, with a handful of ballads for changes of pace. It manages to stay true to the honoree, without anyone imitating him.

Savoy was brought into the project by John Leopold, then head of the vast and essential roots music label Arhoolie Records. It was Arhoolie founder Chris Strachwitz, who died last year, who made the crucial Chenier recordings, giving him exposure to a growing audience interested in regional American forms, reaching far beyond the dance halls of Louisiana and Texas where he developed his loud, raw electric sound. (A 4-CD/6-LP box of recordings from the Arhoolie archives, including previously unreleased material, coming from Smithsonian Folkways, is due in November.) Leopold had already recruited Berlin, who had some experience producing albums for Chenier acolyte Buckwheat Zydeco. Strachwitz was a close family friend of the Savoys—Joel and his three siblings called him Uncle Chris—so having Joel involved was a no-brainer.

“I didn’t get into this project as an expert in zydeco,” Savoy says. “I never claimed to be that. I came in because of my connection to the Acadiana music scene, which involves among other things Cajun and zydeco musicians. It was easy for me to call up any of the zydeco accordion players on the project and connect them, because I already knew them.”

He did not, though, know the Rolling Stones. That connection came through Lafayette, Louisiana, guitarist and producer CC Adcock, who has ties to the Stones camp.

“Early on he said, ‘I think I can get the Stones,’” Berlin says. “And me and John and Joel were like, ‘That would be awesome, but we’re not going to hold our breath.’”

It was saxophonist and artist Dickie Landry, another Louisianan with ties to the Stones, who made the pitch. Landry, who had taken Jagger to see Clifton Chenier at Verbum Dei in the 1980s (an episode colorfully told in author Michael Tisserand’s book The Kingdom of Zydeco), approached the singer when the band was in New Orleans to play the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in spring 2024.

Savoy, who’d already enlisted Adcock to bring in Lucinda Williams in duet with veteran swamp pop star Tommy McLain, adds, “I took it with a grain of salt. I mean, CC’s done some amazing and incredible stuff. But I didn’t think that would ever happen.”

He was almost right. Originally, plans had been made to release the album at this year’s Jazz Fest in early May. And with no confirmation from the Stones, the producers had to move forward.

“In December, the record was sitting at the pressing plant,” Savoy says. “The test pressings had been approved, the artwork was finished, jackets were going to print. And we got word that the Rolling Stones wanted to be on the record. So I stopped everything. We completely resequenced, redid the artwork. We had to remaster, do new lacquers, everything. We basically just stopped and redid everything to be able to include their track.”

It was worth it, and not just to have the band’s name associated with the project. Their performance is outstanding all around, and embodies the concept of the album that Berlin and Savoy put in place: to match the guest stars with musicians from the capital of zydeco in sessions done in Lafayette. For this song, Adcock assembled a band of ace locals, led by Cajun accordionist Steve Riley. Jagger, Richards, and Ronnie Wood added their parts for an explosive combination that captures the thrill Jagger had when he first discovered Clifton Chenier’s music nearly 60 years ago.

When Savoy was brought on board, one of the first things he wanted to do was line up members of families who had been key to zydeco, particularly accordion players. About three years ago he played the Sisters Folk Festival in Oregon that also had CJ Chenier, whom he’d known for years, on the bill.

“Joel said, ‘We’re doing a tribute to your daddy, would you be interested in playing?’” the young Chenier says. The answer, of course, was a solid yes.

CJ Chenier is featured on both the scorching swampabilly instrumental “Hot Rod” with Los Lobos guitarist David Hidalgo and the smoldering “I’m Coming Home” with guitarist Sonny Landreth. The other accordion players Savoy recruited represent a couple of generations who followed the path set by Clifton Chenier: Nathan Williams Sr., Keith Frank, Anthony Dopsie (the son of first-generation zydeco great Rockin’ Dopsie) and Geno Delafose (son of groundbreaker John Delafose) are all bona fide, pedigreed zydeco stars. Cajun musician Riley, Roddie Romero (who straddles the Cajun and zydeco styles) and former Sir Douglas Quintet/Texas Tornadoes member Augie Meyers represents the Tex-Mex of his state, where Clifton Chenier was a regular for years.

There’s another Chenier here as well: Sherelle Chenier Mouton, granddaughter of Cleveland Chenier, plays rubboard on several songs. And furthering the family legacy, all profits from the album are going to the new Clifton Chenier Memorial Scholarship Fund at the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, created by Valcour and the school.

The Stones track was not the only one with a little drama around it. Steve Earle was excited to come in from his home in New York to record with the Lafayette locals, including Dopsie on “Just Like a Woman”—not the Dylan song, but a jump-jive number showing the considerable Louis Jordan influence on Chenier. But when he landed, he got word of a family issue and had to take the next flight back.

“I literally had to turn around,” he says. “But I can testify, the gumbo is totally there at the airport. It’s really first-rate. So I had the gumbo and got on another plane and they cut the track that day. And I did my vocal in New York a month later, which was a bummer. But I’m really proud of my vocal on this. I did some things vocally I’ve never done before. It was pretty inspiring.”

Obviously, CJ Chenier’s place on this album is crucial, as is his perspective. By the time he was a teen he knew his dad was a big deal. By his 20s, when health issues prompted Clifton to bring CJ into the band with the idea of eventual succession, the son was fully aware of the legacy he was being handed.

“I turned 21 on that first tour,” he says. “I didn’t know how many people loved him until I went out on that tour with him. I knew people back in Port Arthur and around Louisiana loved him. But I didn’t know what it was after he left those boundaries and went out, how vast it was, how many people all over this world, everywhere. Europe and the United States and everywhere. People were crazy about him. And that’s what made me realize the magnitude of who he was and what he was doing.”

Backstage at the Music Machine in Los Angeles in 1988, at the first show for him after his dad’s death, CJ said, “The crown was his. It’s not something to be handed down. It won’t fit any head but his.”

“Yep,” he says now. “That’s it. Still feel the same.”

But what does it mean to be the King of Zydeco? Comparisons read like a Mount Rushmore of American roots music.

Berlin floats both Muddy Waters and Charlie Parker.

“Clifton took the music that influenced him to the same place Muddy took the music that influenced him,” he says. “It was loud, fast, sweaty, and powerful.”

Earle suggests Bill Monroe.

“Bill Monroe literally invented an American art form,” he says. “There was no bluegrass before him. There was no zydeco until Clifton. It was just Black Cajun music. There were button accordions, doing the same things that the white players were doing. Then Clifton got a piano accordion that makes some things possible.”

The case can even be made that Clifton to his music what Louis Armstrong is to jazz. CJ Chenier embraces that take.

“Before him there was no zydeco,” CJ says. “It was ‘la la music.’ He was open-minded. He once told me, ‘You hear something you like, you make it yours.’ He had a lot of influences like Louis Jordan, and he played Fats Domino stuff, he played Ray Charles stuff. He would sit down, learn off the records, and just play them his way.”

Clifton Chenier came up with his sound almost by necessity. He was born in rural Opelousas amid the bayous and prairies, both the Cajuns and Creoles living rough as farmers and trappers. The music they made drew on various folk traditions mixed with early country, blues, and popular songs. And it wasn’t unusual for them to play together. Black button accordionist Amédé Ardoin and white fiddler Dennis McGee were a key duo in the 1930s and ’40s, playing weekend dances and barroom gigs, (The music the two made is often tagged as the source for both modern Cajun and Creole music of the region.)

Post-World War II industrialization, particularly the oil boom along the Gulf of Mexico, created new needs for local entertainment for the workers. Chenier himself worked in oil refineries—it was his day job in Port Arthur, Texas, for part of CJ’s childhood. The dancehalls got more crowded, the crowds got noisier, and electric blues and early rock ’n roll swept in.

“Basically his accordion was electrified,” Berlin says. “Which changed everything for everybody. ’Cause once you electrify something, all the other instruments have to, too. Either get louder or thicker or harder to meet that challenge.”

Two things, though, kept the strong connection to the origins: Cleveland’s rubboard and the Creole French dialect used in most of the songs.

“I speak French too, but it’s a different language,” Clifton said to the largely Francophone crowd at the 1975 Montreux Jazz Festival, as heard at the start of the live album recorded there.

So what’s the state of zydeco today? It’s been through a lot of phases, successive generations bringing in rock, funk, hip-hop, and modern R&B to various degrees, sometimes taking things far from the origins to the point that a connection seems lost.

“I think a lot of them don’t even know,” he says. “I’m about to be 68 years old, and my dad’s about to be 100. And you’re talking about kids, like 20, 25, 30 years old. So there’s a 50- or even 70-year gap. They’re not going to sit down and start researching. They’re going to play what’s going on right now.”

While CJ doesn’t find a lot of new stuff that he likes, he gets it. “Everybody wants to incorporate what they know, what they might have grown up with,” CJ says. “Even myself, I wanted to put some funk here and there. But I didn’t want to just funk everything and leave the real article behind. I put some here and there, but I still try to stay true to the music.”

“I still play the blues, man. I still play waltzes. I still play ballads. You know, zydeco style. So they say old school. I say real school.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.