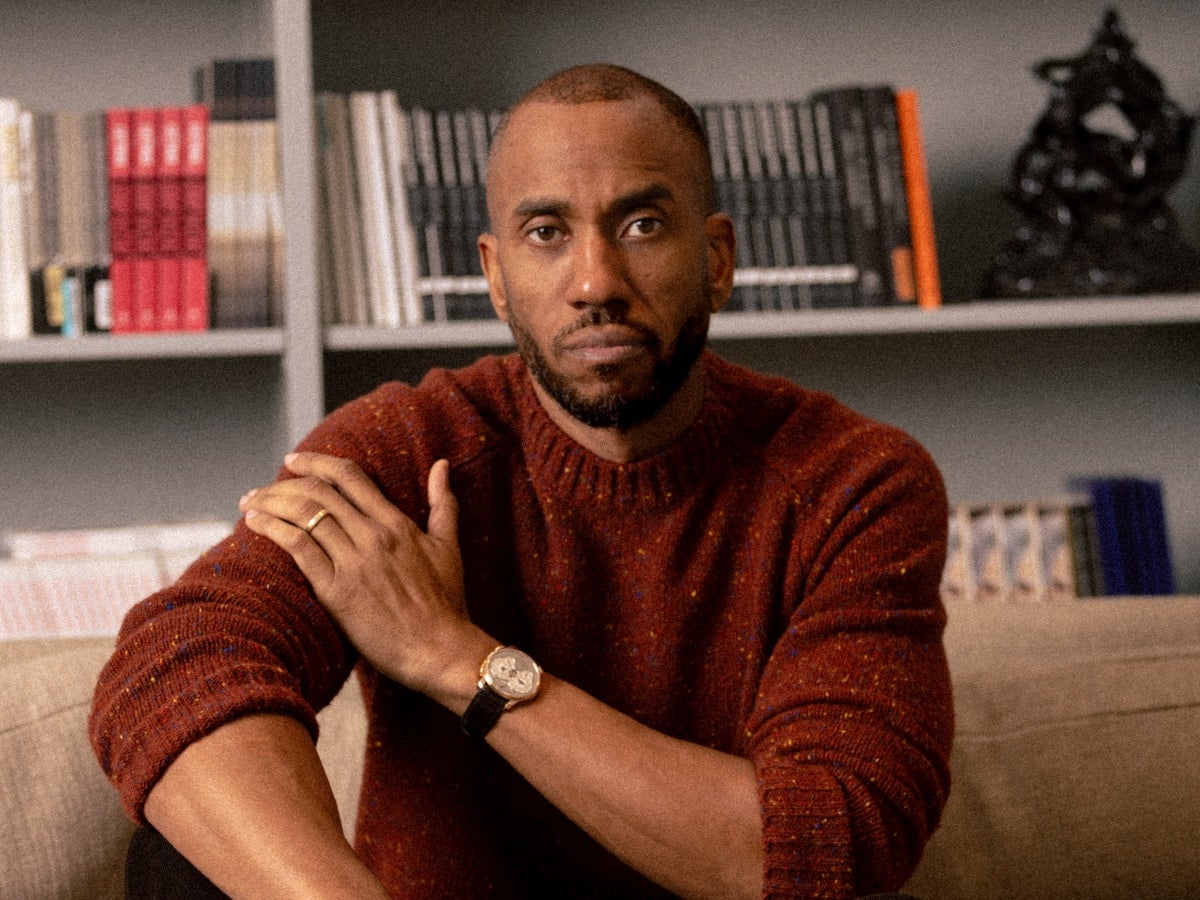

To have your past, present, and future selves greet the world at parity is the kind of vulnerability that artist Rashid Johnson has been nurturing for nearly 30 years. Surveying personal and collective histories, his prolific practice reveals that maybe time is a map to our souls, harnessing the marks of our existence to lead us back to ourselves. His interior disarmament is a humble offering of love, empathy, and care for all who encounter his work.

The Chicago-born, New York-based artist defies conventions of deep, critical discourse working across painting, sculpture, filmmaking, installation, and photography to center care as his primary inquiry. He is a steward of both the history and humanity that has shaped his worldview with works that invite the collective into the innermost facets of his consciousness. While strictly canonical interpretations of his practice might largely herald his scholarly prowess, it is Johnson’s iterative exploration of the self and our human experience that distinguishes him as one of the seminal artists of our time.

“When you make admissions about your own limitations, then often other people are willing to do the same,” Johnson tells ESSENCE. “In that space of honesty, there is an opportunity to have a real dialogue that is rooted in sincerity.” He articulates the intuitive reciprocity not only at the heart of his current Guggenheim retrospective, A Poem For Deep Thinkers, but his oeuvre in its entirety.

As the son of an African History professor, Johnson received a form of intellectual inheritance where critical engagement was a requirement in his rearing and, to a degree, a self-imposed obligation as he sought to forge his own artistic path. He pays homage to his forebearers— Black writers, artists, and philosophers—by way of ideological and representational interventions, often positioning his personhood as his foremost subject for interrogation.

“When you grow up around so many books and in a community where people are so educated and invested in intellectual engagement, you start to wonder, ‘How am I ever going to catch up and acquire all of the knowledge that I would need to be a part of these conversations?’” he reveals. It’s the one of the earliest anxieties to manifest in his project, evidenced through visual mimesis and literary semiotics that demonstrate the formative impact of his antecedents. But as he matured the confidence within his standing solidified, it opened dialogue for a new perspective on the bounds of critical engagement, one that turns to the spiritual.

“Spirituality and our relationship to it is inherently a very expansive critical space and it doesn’t come at the expense of intellectual activation,” he tells ESSENCE. “It actually is an incredible assistant to it.” Whether it’s his Anxious Audience (2019) peering across the rotunda, transfixed on a young Johnson ten years their junior in Self-Portrait with My Hair Parted Like Fredrick Douglas (2003), or Bruise (2021) and God (2023) paintings extending a gestural interpretation of his psyche, implications of the soul are ever-present in his work.

Rather than evade his innermost uncertainties, Johnson welcomes them as references in his almost alchemical interrogation of ideas, materials, and interiority. In some ways, the artist has made consciousness his most salient subject. He attributes these insights to a form of ‘intellectual prayer’ that reveals the power of quiet that can only be found within.

Often interrogating themes of existential liminality, be it domestic, psychological, or emotional, his work is an invitation into his personhood with a visual language that functions as both intellectual proclamation and spiritual confession. As much as he prompts temporal reflection onto himself and his identity, he poses the question right back to the viewer, his artistic witness: Now that I’ve shown you myself, look beyond me and ask, ‘How do I see myself?’ and more importantly, ‘What is the self?’

Ascending the Guggenheim’s spiral architecture, these questions do not go unanswered as his vulnerability is on full display. We meander through time, sojourning with the Rashid Johnson of 1998, 2012 and 2025—along with every version in between. They are all in conversation with each other and with us, shepherded by the discourses that guided him in his self-discovery. Black thought encompassed in history, art, literature, and theory becomes a conduit to the multiplicity of his interiority and Blackness as a whole.

“One thing you get to experience is where I was at different stages,” the artist shares. “Often what you are seeing are allusions to the things I’m actually reading, recognition of the records that I’m listening to, the materials that I’m being introduced to that I think are really prescient in unpacking where I am at in those particular moments.” Whether it’s his transformation of black soap and shea butter into corporeal allegory, or literary semiotics as personal biography, his work is a poetic excavation of the mind of an individual deeply aware of his position and meticulously building the framework for his own examination.

For Johnson, introspection parallels the rigor and stamina akin to cultivating his artistic craft with these meditations on interiority most illuminated through movement and self-care. He shares, “I often prioritize how I feel and the different ways that I can kind of change my experience through the conditions that I expose my body to.” The artist has been a frequent visitor to the Russian & Turkish Baths for over a decade, describing the space as a sanctuary for safety and equanimity. Recently, he transformed the sweltering saunas into a psycho-social crucible of modern day race and gender relations in his restaging of Amiri Baraka’s 1964 play, Dutchman, for the Performa Biennial.

At 48, Johnson is in the middle of many things: his life, his career, and the patrilineal line of himself, his father, and his son. As much as he reflects on our collective past to meditate on the present, he is also looking to the future with joy and optimism as his guiding lights. Those anxieties more prevalent in his earlier works have been quieted by a sanguine anticipation for what’s to come.

Johnson speaks of his deep reverence for the enduring legacy of artists, creators, and educators who “get to add something to this quilt… this expansive, long web of humanity and the human condition, but also recognize how small we are in the history of the world,” noting that his preeminent obligation as an artist is to “lay out the ideas, the things that are interesting to [me] both aesthetically and critically, and then let the audience consume from that buffet.”

As he bestows his intellectual and artistic concerns to his viewers, he is most cognizant of his son. “For me, fatherhood has expanded my understanding of the world more than anything else,” he says. “It has helped me understand how to be a better artist.” That same enthusiasm for all that he strives to impart upon his son—safety, support, care, and intellectual nurturance—are similar to the generous evocations present in his public work.

With time as his circuitous anchor, Rashid Johnson’s prevailing obligation is to be present. Soul-searching within himself and the collective is in service of a long lineage of critical discourse where his mark is one of unapologetic vulnerability and reciprocity.