Atlanta’s King Holiday Observance kept the city’s tradition of a full week of purpose. This year, the King Center kicked off 2026 with packed programming that blended culture, community, and red carpet energy, all while pushing one urgent message to the front: nonviolence is not soft, it is strategic.

The 2026 King Holiday Observance ran January 12 through January 17 in Atlanta ahead of the federal Martin Luther King Jr Holiday with a theme of“Mission Possible II: Building Community, Uniting a Nation the Nonviolent Way.” With Dr. Bernice King front and center, it ultimately framed the week as a reminder that the King legacy is not only meant to be remembered, it is meant to be practiced.

Monday, Jan. 12: MLK Week Opened On Auburn Avenue With Hoops, Hopes And Dreams

The week kicked off Monday, January 12, with Andscape’s “Hoops, Hopes and Dreams” screening premiere and Black Carpet Experience.

Hosted by Dr. Bernice A. King and Dr. Jay, the opening night focused on aspirations, opportunities, and storytelling in sports and culture, setting the tone for a week that would move beyond ceremony and into real conversations about what community building looks like right now.

It also explored the little-known fact that Dr. King was an astute basketball player.

Thursday, Jan. 15: Watts Pulled Up To Atlanta With A Peace Blueprint And A Film That Refused To Look Away

One of the most powerful stops on this year’s lineup came Thursday night at the College Football Hall of Fame, where Nothing to See Here: Watts (a community-led documentary about a county in California) brought an intense, unfiltered look at how relationship building and truth-telling can interrupt violence.

On the red carpet, Bernice A. King summed up the biggest misconception people still carry about the city.

“Utopia. Unachievable. Pie in the sky,” King told BOSSIP, adding that some people treat it like it is weak “because everybody is tough, you know, in this world, you got to be tough. You got to fight back and nothing can be further from the truth.”

Nothing to See Here: Watts brought Atlanta a documentary that does not try to “inspire” viewers with polished messaging. It forces you to sit with what violence looks like in real time, what it steals from a community, and what it takes to build anything stable after the damage has already been done.

The film is mostly shot in selfie mode, and that choice matters. Instead of feeling like an outside production dropping in for a storyline, it plays like a collaborative record. The community is telling its own story in its own voice, with the kind of closeness that makes you feel like you are in the room, not just watching from a distance.

To put it in perspective, this was not a quick turnaround project. The documentary took three years to create, and that time shows how layered the storytelling feels and how many voices were brought into the room.

Hit the flip for more.

Grief, Displacement, And The Daily Fallout People Don’t Always See

Throughout Nothing to See Here: Watts, testimonies about lives lost to violence in Watts land back to back, creating a rhythm that feels like grief stacking on top of grief. The film moves through perspectives from families, middle schoolers, adults, police officers, and gang members, reflecting on how the neighborhood has been shaped by loss.

It also makes space for the everyday domino effects people rarely talk about, including school teachers describing low attendance and the reality that Watts has one public middle school that everyone has to commute to. In the same breath, the documentary shows how displacement forces families to uproot and move, turning instability into something normal.

Tears, Surveillance Footage, And A Storytelling Style That Hits From Every Angle

Visually and emotionally, the storytelling hits with layers. It is not just talking heads and background music. It is tears, yelling, photos, and outpour. It includes typed captions, graphics, audio, and video elements, and even surveillance footage, used to deepen the story instead of softening it.

There are round table discussion moments that feel less like a formal panel and more like a necessary release, like people speaking because they cannot carry it alone anymore.

Everyone’s Perspective Is In It, From Historians To Homicide Detectives

The documentary also widens the lens beyond one set of voices. Community leaders and historians appear alongside homicide detectives, immigrants, longtime residents, and first-generation college students, including a student named Celeste.

It becomes clear that the violence is not only about what happens in the street, but what it does to the way a community functions, survives, and raises its children.

The Film Keeps It Blunt On Purpose, No Gloss, No Filter

The film does not shy away from conflict inside the community, either. It addresses taboo topics that correlate to their community history, such as Black-on-brown violence, including “Mexican Fridays,” described as a time when Black gang members intentionally beat up Mexicans. That level of honesty is uncomfortable, but it also makes the documentary feel committed to truth-telling, not image-protecting.

Even the tone is blunt. People curse. People smoke. They are shown in their everyday element, using profanity, openly smoking marijuana, Black and Milds, and cigarettes, with no attempt to make the pain or the environment more “digestible” for viewers who are used to sanitized storytelling. It is raw, and it is supposed to be.

By the time the documentary reveals the scope of the work behind it, the impact feels even heavier. It eventually captures a pivotal turning point when rival gang members were invited to a private screening as part of a ceasefire attempt. The screening went well, with people sharing perspectives in the room, listening, and moving toward something bigger than ego.

Structurally, the documentary is divided into 11 chapters, with the 11th chapter ultimately being changed back to 1, a creative decision that feels symbolic, like the ending is still a beginning.

Bernice A. King Says Nonviolence Takes More Strength Than Reaction

Before the screening, King told BOSSIP that nonviolence is not about being passive. It is about discipline.

“That doesn’t mean passive. No, no, no. It doesn’t mean weak any of that,” King said. “It takes a lot of strength. In fact, it’s easier to react, you know, it’s easier to act out. It’s much more difficult to restrain oneself and to use higher thinking to figure things out.”

During the panel discussion after the film, King explained why Atlanta was the right city to host a story like Watts.

“What do we say? Atlanta influences everything,” King said. “It was important for us to host this screening and bring it to Atlanta because Watts has lit a fire. We’re so used to instant, we forget that there’s a process.”

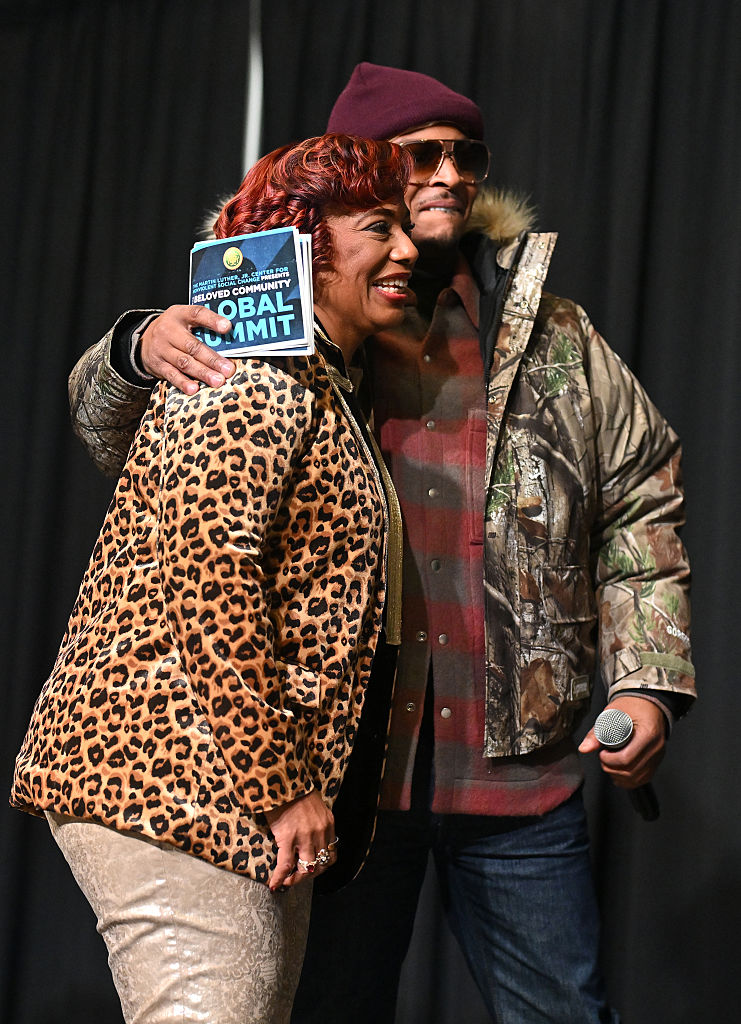

Before moderating, T.I. also grounded the moment with a reminder that unity requires listening.

“We all have to learn to listen to each other despite our differences whether we like it or not,” he said.

Shamea Morton Got Emotional On The Carpet And Saluted Dr. King’s Legacy

Also on the red carpet, Shamea Morton shared what it meant to witness the screening during MLK week.

“Thank you for allowing me to live out my dreams. It wouldn’t have been possible with Dr. King,” Morton said. “It’s important for us this generation to keep his name, the legacy, and the beliefs that he had alive, especially in a time like this.”

She added that MLK’s dream of peace is a journey.

“That’s how we continue to not only create the change, but be the change.”

The Atlanta NAACP Brought A Youth Perspective To The Carpet Conversation

Atlanta NAACP president David Means attended the screening alongside his daughter Alexis Means, who serves as the Youth Works chair.

“The movie is about nonviolence, now The King Center is about nonviolence,” David Means said.

Alexis Means spoke directly to how social media pushes young people into emotional reactions, and why she believes nonviolence still matters right now.

“It taught me a lot about the importance of nonviolence and how you can get your voice heard without having to destroy somebody else in the same process,” Means said. “My goal, honestly, is to bridge the gap between our young people and our adults.”

She also explained why restraint can be powerful when people are waiting for you to crash out.

“They want us to show out. They want us to act belligerent,” Means said. “When we sit in nonviolence… it shows them, hey, these people are smarter than they look.”

The observance wrapped Saturday, January 17, with the Beloved Community Awards Gala at the Hyatt Regency Atlanta in Downtown Atlanta.

Honorees included Viola Davis, who received the Coretta Scott King Soul of the Nation Award, Billie Eilish, receiving the Environmental Justice Award, and Robert F. Smith receiving the Salute to Greatness Humanitarian Award.

BOSSIP’s very own Miykael Stith was on the scene for the gala, capturing moments with celebrities coming out for the occasion.

Other honorees included Warrick Dunn, Dr. Dorothy Jean Tillman, and Dr. Dushun Scarbrough Sr. Corporate honorees include The LeBron James Family Foundation, Sesame Workshop, and Cisco.

Performers included Chance the Rapper, October London, and Goapele. Presenters include Rockmond Dunbar, Karine Jean Pierre, Ian Armitage, and Keisha Knight Pulliam.

The Takeaway: Mission Possible Only Works If People Stop Treating It Like A Catchphrase

By the time Atlanta reached the Watts screening, the message of the week was already clear. This observance is not about nostalgia. It is about accountability, discipline, and community.

Or as Bernice A. King put it, the Beloved Community is not weak. To bring change: It takes strength, and it takes a decision.