The Big Picture

When it comes to the most realistic war film ever made, Steven Spielberg fans are likely to praise Saving Private Ryan while foreign film buffs often think of Come and See, though the reality is that Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers was so revolutionarily realistic in its depiction of the Algerian War that movements as prominent as the Black Panthers and the IRA actually studied its guerrilla tactics. While Pontecorvo is an Italian filmmaker (and the film no doubt benefits from its neorealist style), the film is actually a depiction of conflict stemming from France’s occupation of Algeria, acting as a fundamental text on decolonization without glorifying the participants or perpetrators of the violence portrayed. It’s no surprise then that the film was not only banned in France but even screened by multiple official military groups, including even the Pentagon.

What Is ‘The Battle of Algiers’ About?

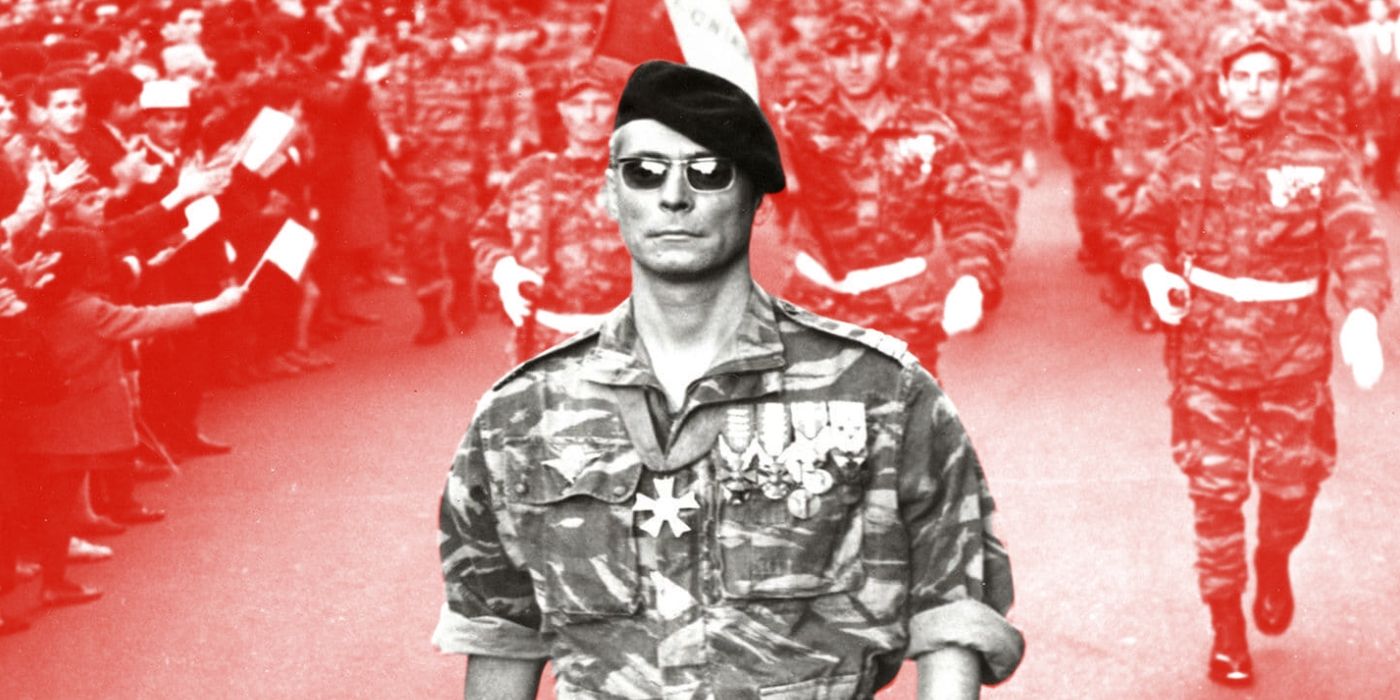

Released in 1966, The Battle of Algiers follows revolutionary Ali La Pointe in the years between 1954 and 1957, in which all the events depicted are recreations of actual happenings at the time. After being radicalized in prison, La Pointe becomes locked in as a member of the National Liberation Front (FLN) against the French Army, as both sides commit atrocity after atrocity against one another all in either the name of freedom or, in the case of France, protecting their colonial interests. Stanley Kubrick, amongst others, has directly cited the film as an influence on their work, but what is it about The Battle of Algiers that goes harder than any other war film before it or since?

How Is ‘The Battle of Algiers’ Shot and Edited Like a Documentary Newsreel?

Though fundamentally rooted in its Algerian protagonist, Pontecorvo’s film is designed to be as politically neutral as possible, particularly as opinions on the conflict in Algeria throughout Europe were divided at the time, with this film providing a global shift in the conflict perceived by the masses. In order to maintain this attempt at neutrality, Pontecorvo mostly cast non-professional actors who had been active throughout the conflict. To complement this effect, the film is cut as if it were a journalistic newsreel (similar to the films of Costa-Gavras), complete with the voice of a ‘broadcaster’ who recaps the events of the war up until the film’s start. In order to provide exposition from the perspective of the French Army, Pontecorvo rarely shows them among themselves directly, instead simulating a press conference through which the Army can voice their opinion on the Algerian nationalist movement and the tactics through which they are combating it. This, of course, like in reality, is revealed to be a facade, with many of the harsher methods of torture used by the French shown later on.

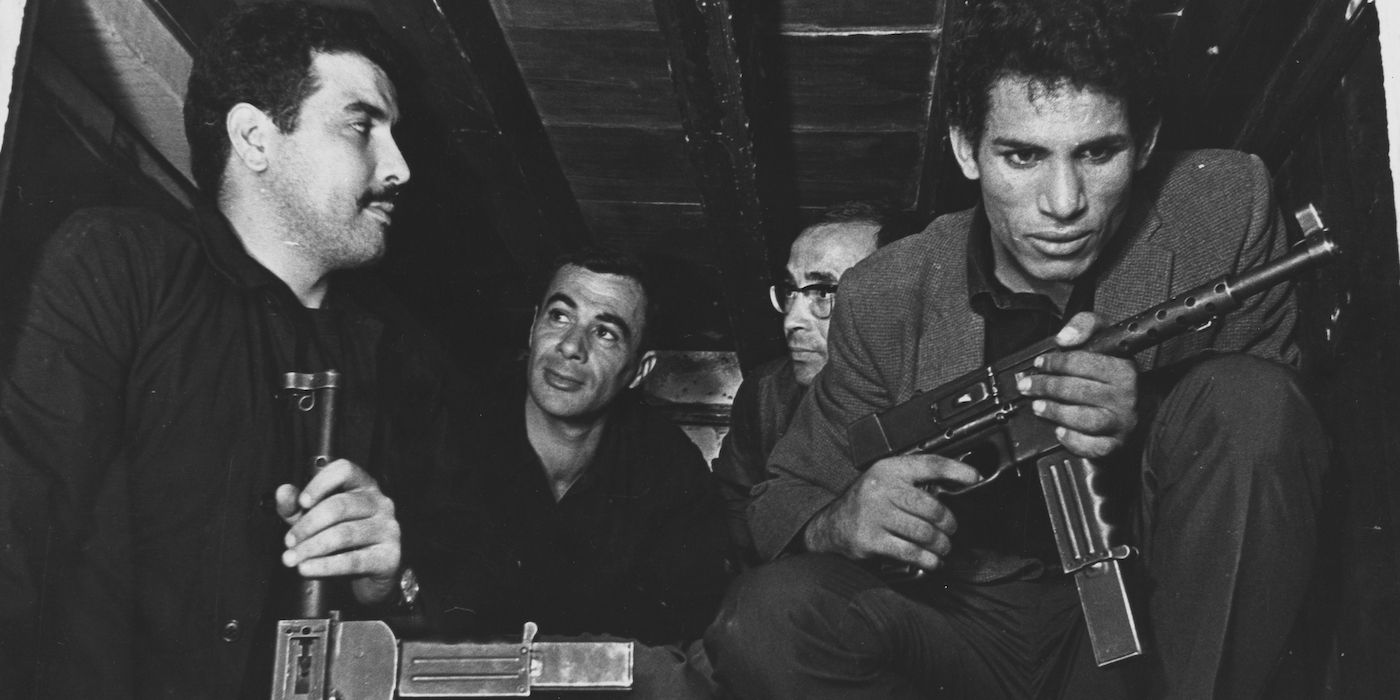

However, even in instances of dramatic battle or private interrogations, Pontecorvo (alongside cinematographer Marcello Gatti) avoids sensationalizing it from a cinematic perspective. Instead, scenes in the streets are shot primarily with handheld cameras from a distance, with the supposed journalist documenting the war a ‘safe’ measure away. Interiors on the other hand are shot in a cinema verité fly-on-the-wall style, complete with wobbly angles, imperfect frames, unfocused zooms, and lots of grain, taking full advantage of the artifice of film to mimic its audience’s perception of what a real, televised war looked like. The effect was so convincing that film historian J. David Slocum even states that American releases carried a disclaimer that informed the audience that not a single shot of newsreel is used throughout the film.

‘The Battle of Algiers’ Doesn’t Make Heroes Out of Anyone

Pontecorvo knew in shooting a politically neutral film about the Algerian War that he would have to avoid heroizing anyone involved, even if those in support of decolonization would naturally align with the Algerian FLN. In philosopher Frantz Fanon’s seminal non-fiction novel on the Algerian War, The Wretched of the Earth, he argues that colonialism and violence are synonymous with one another. According to Fanon, “[Colonialism] is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.” While the merit of the above statement has been contested, Pontecorvo incorporates it without any sugarcoating whatsoever when depicting the actions of the FLN in their attempts to decolonize Algeria.

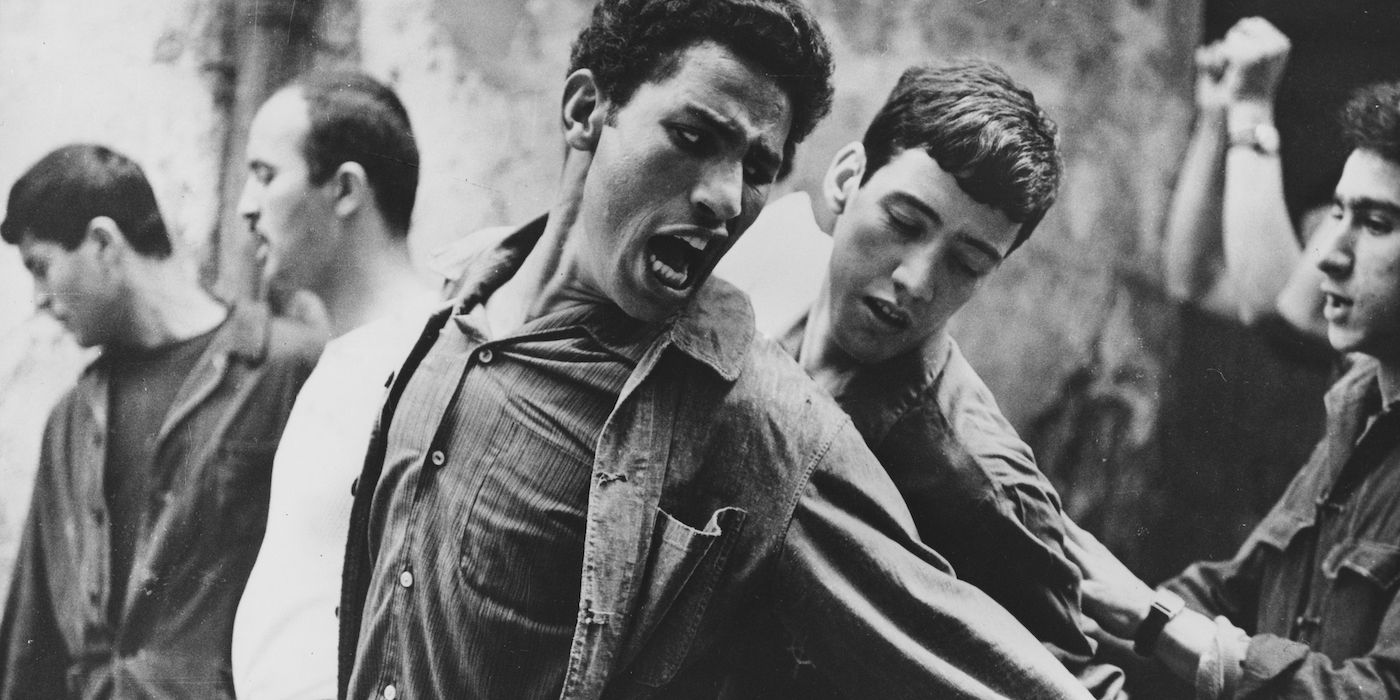

One of the most pivotal scenes of the film involves Algerian females in support of the FLN dressing up as Europeans (with a particular emphasis placed on the shedding of their Algerian identity to do so) and placing bombs in several public spaces within occupied territory. Not only do the bombs go off as planned, but particular emphasis is placed on the innocents whose lives were lost in the carnage, men, women, and children alike. One of the bombers even uses a child in order to make it through the checkpoint under the guise of an innocent mother, showing the lengths she’s willing to go to and the innocents on both sides that she’ll put in harm’s way to succeed. While these characters are the film’s protagonists, the war has made them stray from the heroic ideals that most freedom fighters begin with.

The French Army of course was similarly seen enacting actions of extreme violence against the oppressed Algerian people. Whether public summary executions, extreme acts of prejudice, or horrid depictions of some of the well-documented torture methods used by the French Army, there’s hardly any mythmaking involved in Pontecorvo’s depiction of the conflict. The message in doing so is clear: this is not a work of entertainment as much as it is a document of truth. While the anger of the Algerian people towards the colonizers is certainly righteous, the fact that innocents are targeted and killed shows that Pontecorvo isn’t out to worship idols of war but to comment on a movement.

Which Guerrilla Groups Inspired ‘The Battle of Algiers’?

While Pontecorvo’s film shows a deep understanding of the essential fact that violence can only beget greater violence, such proved the case for his thorough depiction of violence as well. According to Peter Mathews, writing for the Criterion release of The Battle of Algiers, the Black Panthers and the IRA had adapted the film into a training manual. In 2003, the Pentagon even held a screening for commanders and soldiers facing similar opposition in Iraq, urging attendance with a flyer that read: “How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas.” The line appears to contend that though the French Army was righteous in their attempted detainment of terrorism, their methods went beyond what’s deemed sympathetic to the public eye. Pontecorvo (and the majority of the film’s fans) would surely condemn military intervention altogether, though the fact that the film could be screened and appropriated for both guerrilla movements and the U.S. army showcases its incredible efficacy as an unbiased document of brutal warfare.

This wasn’t the only time that the film’s revolutionary message clashed with its pragmatic and unbiased approach to the conflict, having been appropriated by counter-insurgency schools in Argentina. At some point during the tenure of archbishop Antonio Caggiano at Argentina’s Navy Mechanics School, the chaplain had reportedly added their own religious commentary to the film and showed it to several counter-insurgency classes. A former student recalls the experience in stating that torture was not seen as a moral issue but as a weapon, just like any other, elaborating: “They showed us that film to prepare us for a kind of war very different from the regular war we had entered the Navy School for. They were preparing us for police missions against the civilian population, who became our new enemy.” It’s a strong example of the messiness that comes with portraying any conflict from an unbiased lens, almost recalling the bros who continuously misinterpret the meaning of David Fincher’s Fight Club, though even sadder here is the fact that the film was used to perpetuate authoritarianism rather than abolish it.

The truth behind most Hollywood war movies is that while all openly declare themselves anti-war films for marketing purposes, very few live up to the moniker. Throughout the majority of these films, there’s a consistent underlying spectacle to all the carnage as well as a camaraderie to be found among the soldiers that ultimately sensationalizes the idea of war to a dangerous degree. Stanley Kubrick condemned Spielberg’s Schindler’s List for that reason, stating that an accurate depiction of the Holocaust could never be funneled through a celebration of the 600 people its protagonist saved, as all war movies are pivotally about failure on a humanitarian scale. It’s movies like The Battle of Algiers that opt-out from entertaining or even tugging on one’s heartstrings, choosing instead to inform, depicting these horrific cycles of violence for what they really are: void of any glory altogether.