This article is a weaving together of original writing by Eric Avery with some personal history he told Matt Thompson on a rooftop one sunny day.

We left Los Angeles as a band in the mid-’80s in a Winnebago — bouncing out of town as I hammered the stuck plunger of a heroin-loaded syringe against the RV’s inside wall while trying to keep the needle in my vein.

More from Spin:

THE 10 GREATEST SMACK TRACKS!

RSD Black Friday Bonanza: Billie, Beatles, Kacey, Jane’s

Jane’s Addiction Release New Single Despite Tour Cancellation

As we drove out that night I remember feeling that it was the beginning of something big. But I had no idea that it was the first travels on a road that would wind in and out of knots and runs and twists which would eventually place me here in a chair writing about being in Jane’s Addiction as a 58-year-old man. I’m still here.

That night all I knew was that my musical life was getting much bigger. Until that point our shows had happened within a geographical postage stamp. We rehearsed off a Santa Monica alley in a punk clothing-store, NaNa’s shoe warehouse (the site of my last proper job); we played at The Scream, a club that took over a downtown hotel’s basement, and at Hollywood’s Roxy. The remotest frontier on the Jane’s map might have been Safari Sam’s in Orange County.

Now we were in motion.

Yet deliberately plunging into space, into the beyond, really began for me at the age of about 12 with the adventure of drugs — acid in particular, and mushrooms. I’ve always been a little dissatisfied with the world as it is, and looked for other routes through it. Initially it was books. Books were my first drug. But acid gave me a tangible sense of adventure.

My parents didn’t know: acid was my own path. I was really shy, an introverted kid, and I was an epileptic — grand mal seizures since the crib — which makes you feel like you’re really not like other people. You have such a visceral experience of something dramatic happening to you that not one other person at your school goes through. It happened often enough to be a thing, and kids would make fun of me. And I liked to surf alone, so it was always in the back of my mind: what happens if I go out now? Boom, I’m done. Or if I was up high on a ledge — I could go right now. It left me feeling constantly physically vulnerable.

So I didn’t fit, but now with acid me and my friends were going someplace that not everybody goes, and it’s a special place. That’s what acid was. And it certainly did expand one’s horizons, making one conscious of the power of the mind and what was possible.

I had a friend who lived on Hilgard, right across the street from the UCLA campus. We would drop acid and wander through the university at night. It was basically a free roaming area, with a botanical garden, and we would go wandering with pieces of chalk, drawing on the ground and talking. It was kind of philosophical — just meandering on acid contemplating being a human. I’m still doing that.

My best friend in grammar school was Chris Brinkman, who would become Jane’s Addiction’s guitarist in an early iteration of the band, having first played guitar in my high school band. From the age of about 12 I’d hang out at Chris’ house in West LA where he lived with his mom, Jeanne Crain, a ’50s movie star. On the cover of Life magazine there’s an amazing picture of her in a bubble bath, with a bubble on the tip of her finger.

They lived in a mansion with a roundabout driveway and pillars in front as you approached. When you went in the front door the place was carpeted with bright red shag carpet, and unkempt, and there was a curving stairwell that went up to a balcony inside the house. On the way up the stairs were portraits of Jeanne as a young woman. She was crazy beautiful when she was young.

I wouldn’t knock on the front door when I went to the mansion. I’d climb a small tree at the side and go in a den window which was always left open, and then wind my way upstairs. On the way to Chris’ room I’d pass Jeanne’s bedroom. The door would be open and I’d peek in. She was always on her big, ornate bed with an early cable TV box. She sat there under the covers eating pills and drinking and watching TV.

She was a total druggie, alcoholic, pill person, but every once in a while, like for Christmas or something, she would make an appearance. She would come down and sit at the head of the table and be the most charismatic, amazing woman. Then she would disappear, and I wouldn’t see her for six months, except in glances here and there. She was a goddess to me.

I liken Jeanne to Miss Havisham in Great Expectations or Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard. The mansion was dilapidated, the pool all overgrown with algae, and while the property wasn’t entirely a mess it felt kind of abandoned, except for Jeanne in her room and Chris living upstairs in the back where he drew on the walls and could do whatever he wanted. It was kind of amazing: American Gothic; cinematic.

Chris’ dad, Paul Brinkman, whom Warner Bros had put on contract as a double for Errol Flynn, came by once in a while but generally he lived up on his ranch in Santa Barbara.

And Chris was amazing: beautiful and mysterious and talented. He could play guitar, and when he wrote a poem they published it in our grammar school newsletter. Chris was just fucking brilliant and and charismatic and crazy. I was kind of in love with him.

After a few years with drugs Chris and I were doing everything, trying everything. The first thing we shot a lot, when we were 17 or 18, was speed. It was definitely for the physical thing, the rush, but it was also like, “I’m in the fucking high country now — I’m fucking with death.” It was exciting.

But there was more crashing and burning during the three months that we were shooting speed than at any other time, because you do a hit and get that amazing, literally almost orgasmic, rush, and then you’re like, “Oh, now I’m just on speed. I want that rush again.” So you do more speed; you get that hit again, and now you’re on a whole shit ton of speed and it feels fucking terrible. You’re thinking, “I want my head to explode.” Then you do more. During that time people around us were going to the hospital, having nervous breakdowns — all that drama.

Then there was heroin. Heroin had a mystique about it, so when I first did it I was really excited—thrilled by the idea of doing it. But the actual feeling of being on it? I threw up. That first time, I didn’t think I was ever gonna get strung out on heroin because I really loved the excitement but didn’t actually like the feeling.

Obviously I got over that. Then it became that I didn’t want to do anything else.

I ran away from home and when I went back one night there was an interventionist at the house who convinced me that my life was fucked up. So I went to rehab where I met Carla Bozulich — later of cow-punk band, the Geraldine Fibbers — who became my on and off girlfriend through my youth.

She knew Perry Farrell, and when we were talking on the phone one afternoon she asked if I knew his band, Psi Com. I said they blow — they’re just really derivative of English music. She was like, “Oh, okay,” and started talking about something else.

Later in the conversation I asked, “Wait, why did you ask about Psi Com?”

“Because they’re looking for a bass player.”

“Oh,” I said. “Actually, Psi Com aren’t that bad.”

My bass playing was kind of over then. I wasn’t in my high school band with Chris anymore; I wasn’t playing. I was going to sell my bass and amp and do something else with my life. But when Carla said that, I saw the opportunity. They knew all the people in Hollywood — the cool people — so I went, “I’ll do it. I’ll audition.” That’s how I met Perry.

The day I auditioned, the guitarist was somewhere else so I played with Perry and the drummer: just the three of us. We were doing stuff like, here’s a thing, here’s a chord progression, here’s a bass line. And that was “Mountain Song.” It happened that day: it was spontaneous—it was me going “da da da da da da da da; duh duh duh duh ba ba ba ba.”

If I’d just let it go when Carla asked if knew Perry’s band, how much of the world would be different for me—and culture? There’d be no Lollapalooza, for example.

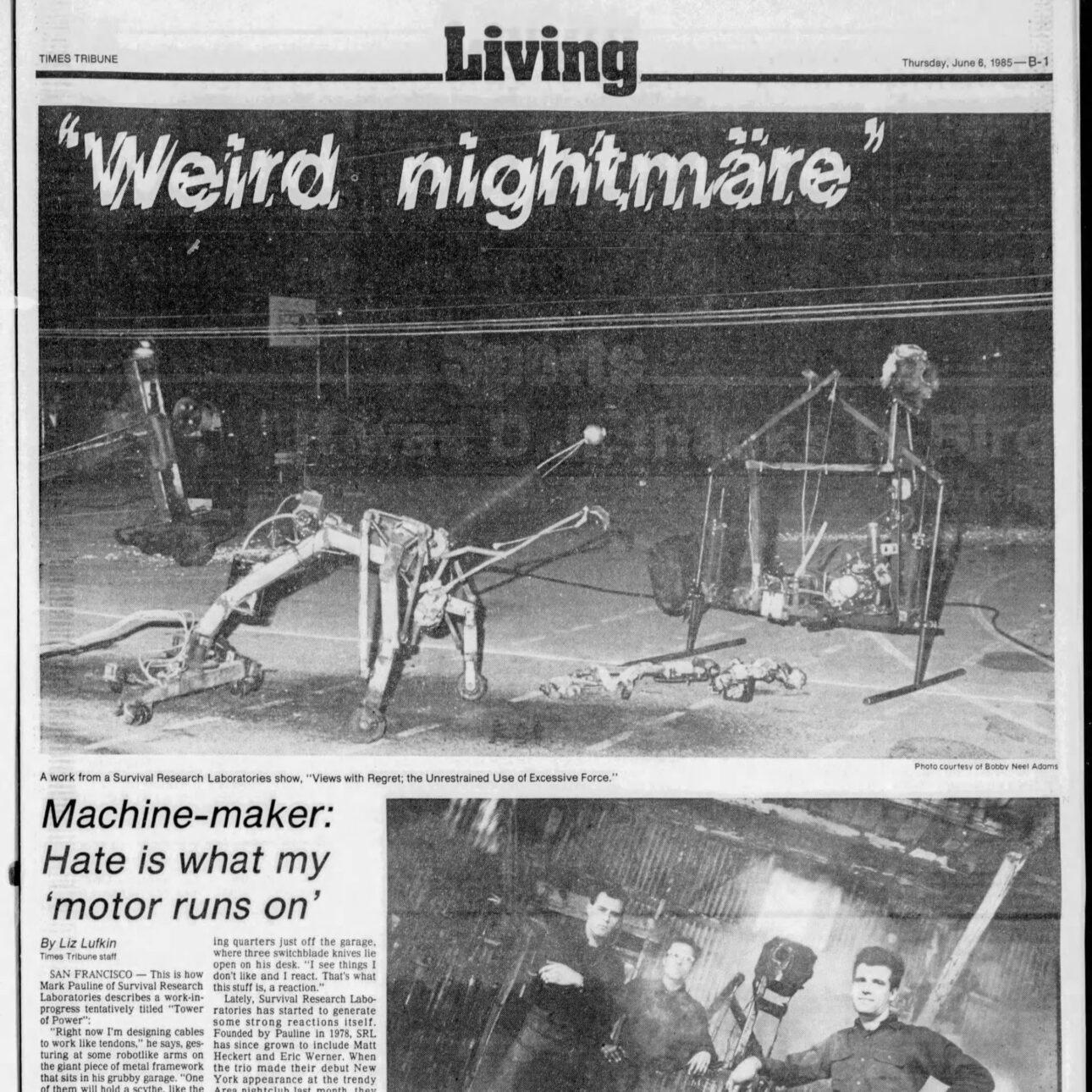

When we met, Perry was an usher for Survival Research Laboratories. They did performances on the cement riverbed of the LA River with home-built machines destroying each other. I signed a waiver saying they’re not responsible for the audience getting injured if anything goes wrong, and then I stood next to all these machines shooting each other and cutting each other up. They even had catapults. It was fucking amazing — I was a huge fan.

It was also part of a movement where people were talking about primitive tribal ritual and the power that it can have in contemporary society. I was introduced to it by Perry, who was friends at the time with an anthropologist at UCLA who tried unsuccessfully to do scarification on his head. The UCLA guy got little incisions and was supposed to rub salt in the wounds so they would stay angry for longer and it would scar, and he did that and went through all the pain — it hurt like a motherfucker — but it wound up healing anyway and you couldn’t see anything.

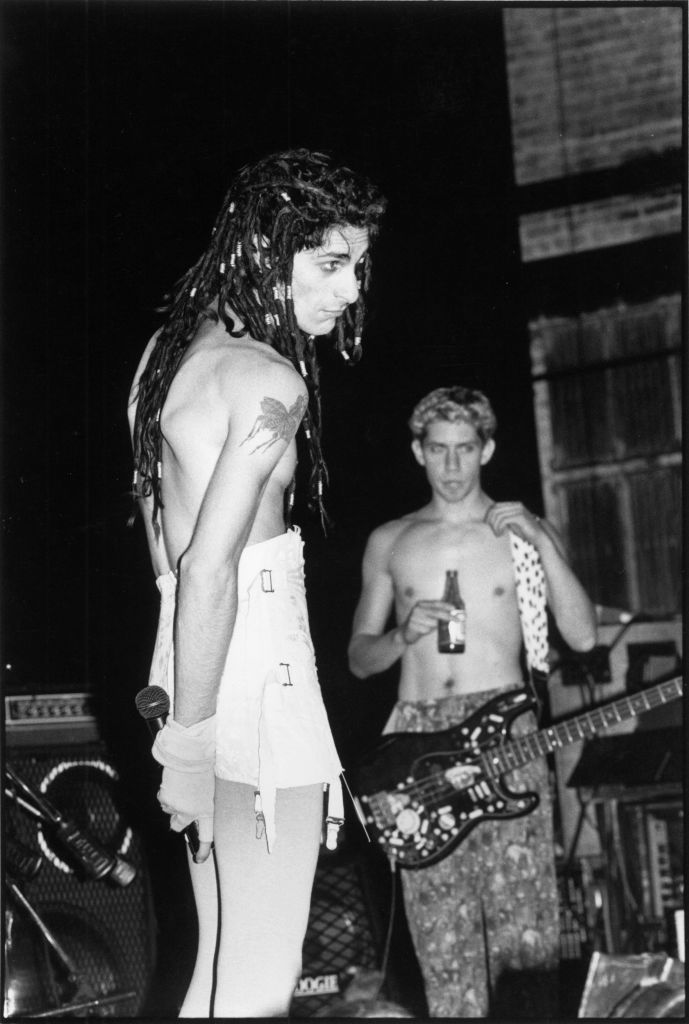

Perry was the most interesting, unusual, charismatic guy I’d ever met, and he became sort of my older brother. He introduced me to the modern primitive movement, and I took to it — it was part of my bass playing: it was about being basic, and playing live was about being physical. It didn’t really become a full workout until years later when I got sober and stopped doing drugs. If you see the early footage of Jane’s, there’s a lot of me just standing around — which was harder than it looks as I even had trouble standing upright — because I was just so fucked up all the time.

Perry found out you could get a $10K arts grant from a place downtown — on Wilshire, across the street from MacArthur Park. So we went there and I banged on a chemical drum while he made noises. We didn’t get the grant, but that would become a Jane’s song called “Chip Away.” In Jane’s, with rare exceptions, any idea you had wound up becoming a thing — because the building blocks were basic: you were just trying to figure out a way to make sense of something musically. You weren’t writing like Paul McCartney or John Lennon. Instead, it was, “Here’s a noise—what’s the next noise? What sound makes sense with this sound.”

A friend recently said he heard some early demos, from before Dave Navarro, and was amazed at how much it sounded like Jane’s — the Jane’s that we became in full flight. And Stephen Perkins, the drummer, recently said to me that he has all the cassettes from that time, and that he likes the demo versions better than the album versions we wound up doing.

Early on my friend Chris Brinkman was our guitarist, playing in the first show we did at the Roxy, but he was always dissatisfied. He wanted to be in a band that was more like Savage Republic or some other local group we’d seen. I remember it that Chris left, but I think Perry remembers it that we kicked him out. Either way, I know he wasn’t satisfied.

As things started to take off with Jane’s, I just started spending less time with Chris, and with most of my friends, really. But years later, after Jane’s, when I was doing my own band — Polar Bear — I reconnected with Chris, and I asked him to come play in Polar Bear. Chris came, but he was like, “Yeah, well, I’m just not really into this kind of music. I want to do stuff like Smashing Pumpkins.”

I said, “You just don’t want to be in a band with me. When I’m in a band that’s like Smashing Pumpkins, you want to do more interesting. And later, when I’m doing more interesting, you want to be in Smashing Pumpkins.”

Chris died of a heroin overdose in 1997. He was 31.

As for the years that Jane’s really broke through and got momentum, those years after we stumbled into the Winnebago, I don’t really have a tangible memory. I was either too fucked up on drugs or just so concerned about things: about my place in the world; about what was happening to the band; and about the relationship between Perry and me. There was always something for me to worry about. Early on, when we brought in Dave and Stephen they brought in this regular rock sound, and to me it sounded too Led Zeppelin.

I was always self critical. It’s in my character. And when I was still getting fucked up, the drugs were hard work. Inevitably at some point on a tour you’d got dope sick. When you left LA, you were like, “How do I push this out?” Like get some amount or something to push out far enough so that maybe you can meet somebody, or some circumstance will present itself to keep going. One of the tricks in the States was going to methadone clinics in the city you were playing in, and asking around: “Hi, will you be my friend?”

There was no internet, so when you’d travel internationally you’d have no idea where to start — where to go — so fans become helpful. You’re really looking for fans to connect with. And because of our reputation there was a contingent of junkies in London early on that took care of me and Dave, so we had a port in the storm.

But inevitably it breaks down and at some point you get dope sick. Compared to my junkie friends at home, I spent so much more time dope sick than they did, because they were on the hustle every day with the predictable resources and access of home turf.

Touring’s grueling: physically and emotionally. And when you’re dope sick on top you want to jump out a window, but you play through it and get well.

Until you get home again.

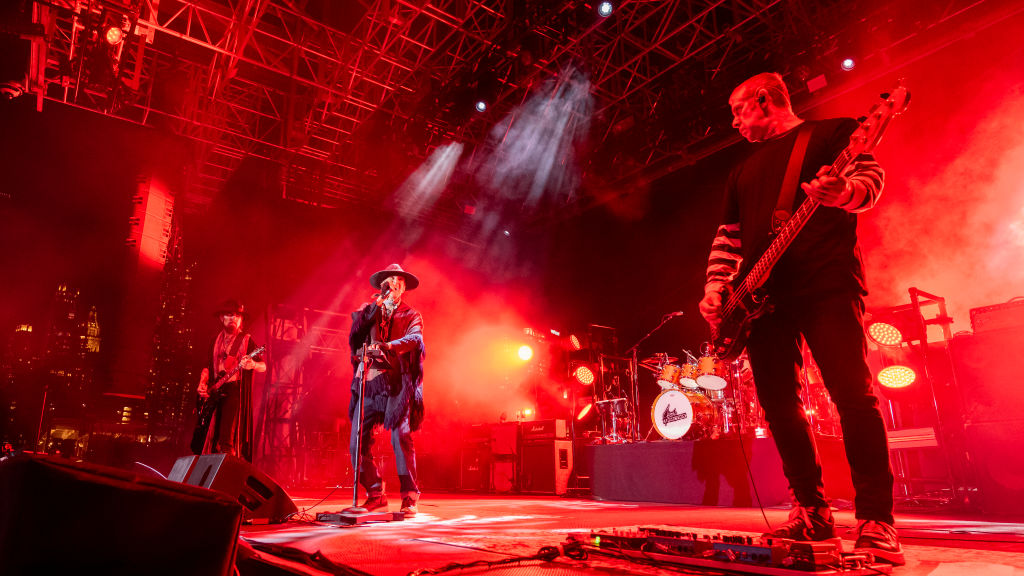

And part of our appeal was this isn’t gonna last. Someone’s gonna die. They’re gonna break up. This will not last. Every time we played it was chaos. Every show felt like the last show.

Jane’s drug consumption was infamous — but I stopped. People are often surprised by this, but the last time I did heroin was August 19, 1989, so I navigated all of Jane’s Addiction’s large-scale success without a drug in my system.

I recorded our second Warner Brothers record, Ritual De Lo Habitual, and spent the entire first Lollapalooza tour, clean from all dope and alcohol. In Jane’s last couple of years, I lived some of the most potent experiences possible in a musical life clear, present, and available. Still engineered for adventure and exploration, the clean me now focused differently on life’s heightened moments, wanting to glean as much as I could from them instead of staggering through them in a stupor.

All the power becomes concentrated into a single point

This new high was constructive instead of destructive, experienced in real time, and with both eyes wide open. To be completely present and observant in life’s big moments — those moments that easily flash by when we are clouded or overwhelmed — is to experience life’s enormity distilled into bite-sized wonder. All the power becomes concentrated into a single point.

One point that stays with me is Jane’s 1991 show at Madison Square Garden.

As a teenage stoner, I went over and over to midnight screenings of Led Zeppelin’s movie, The Song Remains The Same, at a local theater in Westwood. Zeppelin’s live footage starts in the darkness of an unlit stage. As the crowd roars, a caption on screen reads: “Madison Square Garden, New York City.”

Now, on an April evening a decade after all my late nights at the Westwood where I soaked up that volcanic peak of rock, the Garden belonged to Jane’s. I was 25, turning 26 tomorrow, and I was stone cold sober.

The house lights went out. The huge venue was dark. The roar of eighteen thousand fans erupted. I remember the bare handful of people turning up to our early shows at clubs like Raji’s in Hollywood. Now the crowd noise tore space and time apart. I stepped into the roar, walked to the front of the darkened stage, and stood singular and still amidst inchoate frenzy.

Most nights I started the first song of our sets. Many Jane’s songs begin with the bass line, and we often, ritualistically, opened evenings with a dimension-shifting instrumental called “Up The Beach”—as we were about to tonight.

Standing on the edge, bass slung and ready, I opened myself to the huge roaring of the crowd. Listen, I thought. Pay attention. This is happening. Right here. Right now. Only after I really breathed that in did I strike the first note.

On heroin or drunk I’d never experienced such moments.

But being sober in Jane’s Addiction is fraught, because I’m the only one who’s not on drugs, and by now Perry hates me and his entourage hate me. Like when I get in the van I just get in the back row and then in pile Perry and his entourage. It’s uncomfortable. From our punk genesis, from me and Perry banging a chemical can and finding the magical power-flow from one sound to another, building a band and finding ways from a coiling murmur to a heart-scream, from a melodic mood curve on the bass to a megatonnage of guitar and percussion, we’ve deconstructed, decohered as a collective. Jane’s has become this thing that I don’t have much of a feel for anymore. We’re not writing new music. We’re not doing stuff. I’m just playing shows and then going back to my hotel room, living my own life, and the band is something over there that doesn’t feel like my band anymore.

At one point I got recognized at a bookstore, and some guy was asking me about the new record, which was Ritual. I said, “Well, you know, for me it’s overproduced. I wish it was a little more raw.” And that guy was the gossip-column writer for BAM magazine in the Bay Area. He wrote that I said that, which then made Perry angry, and at some point Perry said that I was coming to a meeting where everybody was gathering to decide whether or not they were gonna kick me out of the band. It was so weird.

I show up at a meeting thinking I’m really going to have to stand in front of management, the money people, our record producer Dave Jerden, and the band. So I show up, feeling social anxiety about what’s happening and what’s at stake. They start talking all sorts of business shit and this and that and then it’s done. Nothing happens, and we all leave.

So I asked Dave Jerden, the producer, “What happened with deciding if I’m still in the band?”

He went, “What are you talking about?”

“Oh,” I said. “Never mind.”

But in Perry’s world it’s another strike.

It could be different, though, like when MTV wanted us to do Unplugged but I didn’t want us to. Part of the reason we maintained any sort of cred is that there were key moments where we really demonstrated that we genuinely were who we were. There are times where I know that artists who people assume are really genuine are not — they’re strategic —- but Jane’s wasn’t like that. It was genuine. So when I said that I thought MTV was bad for music and I didn’t want to have anything to do with them, that was what I really thought. Perry wanted to do Unplugged, and Dave and Stephen probably wanted to, but Perry said, “Eric doesn’t want to do it, so we’re not doing it.” They all understood that we were a band and if one member doesn’t want to do something then we don’t, even if it meant less eyeballs or whatever. We would leave money on the table.

Being the only sober member of a band with infamous proclivities could also be funny from my perspective, like during our first show at the very first Lollapalooza in 1991. We’re playing: I’m doing my thing; Stephen’s playing; and then I hear the guitar go out, but I don’t look up because Jane’s is always chaotic and I was used to people stepping on cords and shit. So I don’t think twice and keep playing —- just drums and bass. Then the drums stop. I look up and there’s no one on stage. Now Stephen’s walked off. I take off my bass, shrug to the audience, and walk off. Turns out Dave and Perry got into a fist fight after accidentally bumping each other, and they’d tumbled down the stage-ramp fighting.

No longer did I have to deal with the obvious, daily resentment of Perry and his entourage

By the end of Jane’s I felt so alienated from the band and from the experience of it all that breaking up was a relief. No longer did I have to deal with the obvious, daily resentment of Perry and his entourage, and with how negative everything had become.

A week later I went to Big Sur, rented a house, and stayed there.

When the reunion tours began I wasn’t interested. I saw that they were doing a really bad job of it, but I didn’t want to celebrate them failing — just as I wouldn’t have wanted to see them doing great. So I just removed myself from it entirely until 2008, when I agreed to play a show at the NME awards, as a way to honor the past, and also because the NME mattered to me. I grew up loving the English bands it covered.

So I played the one night. The next day our first agent and longtime friend of the band, Marc Geiger, asked me to meet for coffee.

For three hours I sat there as he laid out a plan for Jane’s. He made it seem possible. Have other people run interference on Perry, so I didn’t have to. Stop Perry doing poor covers of Jane’s songs with his other acts. He described recording new music produced by Trent Reznor and a possible tour with Nine Inch Nails. All I’d have to do was play bass. I said for me to do this — to climb back in — there’d have to be new music. Marc said, “Yeah, absolutely. That’s the whole plan.”

I agreed, but almost from day one the promised plan didn’t materialize. It devolved into being really bad and the attempts at new music were terrible and then went by the wayside. But they convinced me to persist by saying that we could come back to new music — just go play some shows: get Perry up in front of people so he gets the feeling of people caring about what he does, and then afterwards we’ll fold that feeling into going back into the studio. I said okay, but it didn’t happen.

Times change. What can’t be reconstructed on demand is ineffable: a combination of time and circumstance, of where everyone’s at and how they come together with an energy and a certain spark. Nor can the time everyone is driven to spend together working on it all happen again — the way when you’re young you wake up and hang out with your friends all day, every day, even if your friends are annoying or kind of crazy.

Looking back at Jane’s, a lot of the writing was done when things were good between us. It was competitive in terms of trying to occupy a creative space: your idea versus his idea. But it was also procreative, and songs could come from random spots, bits, and pieces; the start of something could be a vibe, an idea, a single line on a guitar. That’s when our palette was created. And then some of these components born in the good times were put together later when there was tension.

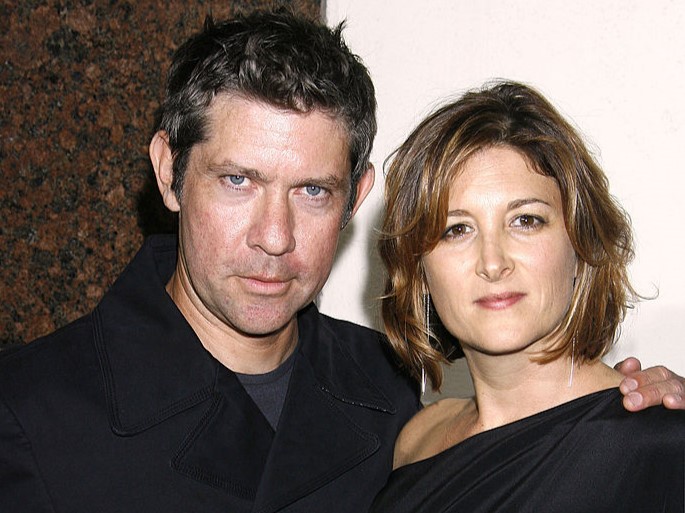

I’ve been thinking about all this recently, and talking about it with my wife, Anabelle. The other night we watched Almost Famous. I’d said to her that I want to watch it again, because the first time I didn’t like the movie even when everyone around me did. I just thought it was really goofy, all that playing at being in a band. But what I said to my wife after we re-watched it was that ultimately I enjoyed the film. I said that there was a point in the film at which the band goes out on stage for the first time, and the Cameron Crowe kid is in tow. The band says to wait over there while they go out on stage, and the camera follows him. Watching this, I was really moved. It’s amazing that I’ve gotten to do this — to be the guy that goes out on stage and makes the noise, and people show up. It hit me that I didn’t have that feeling when I was young, because I was either too cool, too removed, too scared, or too fucked up.

For example, there was no high-fiving when we were on the cover of SPIN. I registered that it was a cool thing that we were, and I remember it was cool that we had a spread in the LA Weekly, but it didn’t land the way that it does in Hollywood portrayals. It wasn’t like, “Yeah! We made it! All our hard work! We wrote the songs and now here we are!” I didn’t have that feeling. Maybe Perry had that experience, but I didn’t.

At 58 I’ve rejoined Jane’s Addiction. What will we do? Will there finally be a high-five moment, or will it go down in flames?

And now at 58 I’ve rejoined Jane’s Addiction. What will we do? Will there finally be a high-five moment, or will it go down in flames? To me, in the interests of creativity and of having the unexpected in life, it’s part of a controlled reversal of changes I made after I got sober. Because having nothing to do with drugs meant getting rid of my difficult friends. I literally broke up with them. But now, in this era of my life, I’ve started putting these people back in. I realized that unlike when I was young, I don’t have to hang out with them every day. I’m no longer that person; I don’t need that from a friend; they don’t need that from me. Difficult friends are great in small doses, because they’re bonkers and they bring something that you don’t find at the mall. So I’ve started spending time with my crazy friends again, but every couple of weeks instead of every day.

And I’m doing psychedelics again — but this time like an adult and in the interests of creativity and cognition. I have a spray of acid, which I haven’t taken to the face-melting level. My goal is to find that great moment when things start to turn on, where everything just becomes a little more bright and visually articulated. I want to titrate up to that spot, and then just stay there. That’s my ideal dose: where you are in a heightened spot but no one would know you’re on acid.

Plus, Jane’s needs difference. In the time I’ve not been in the band they’ve been at about 30 per cent potency. Jane’s On Ice, as a friend puts it. We’ll see how close to a hundred we can get. And now I can better appreciate the clashes in styles, from my post-punk preferences to Navarro’s more classic rock, so now when he does guitar parts that aren’t to my taste I still want them in there. Maybe I’ll hate them now but love them in six months. And it’s not the Eric Avery solo project. It’s a band of different voices.

I welcome variety of experience.

First published as “I’m With the Band” in SPIN‘s print issue of September 2024 — shortly before a now notorious night in Boston.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.