In the January 1991 issue of SPIN, interviewing Perry Farrell, who we had crowned Artist of the Year for 1990 because he created Lollapalooza and broke up Jane’s Addiction, two excellent decisions, I wrote these words:

Every American generation finds its own way to be creative. Whether it’s music, art, bad television, fast food, or just lots and lots of kids, we’ve always found a way to leave our mark. Each decade has its own indelible character; at the beginning of a new one journalists hold an unofficial contest to try to be the first to characterize, and more importantly name, the latest developments in our culture.

More from Spin:

Album of the Year: The Cure’s ‘Songs of a Lost World’

The Best EPs of 2024

Jewel Wants You to Know That You’re Not Alone

I went on to suggest that the emergence of “alternative culture” into the mainstream via Lollapalooza, movies like Slacker, and books like Generation X (which we excerpted in that same issue!) all suggested “a philosophy of rejection”.

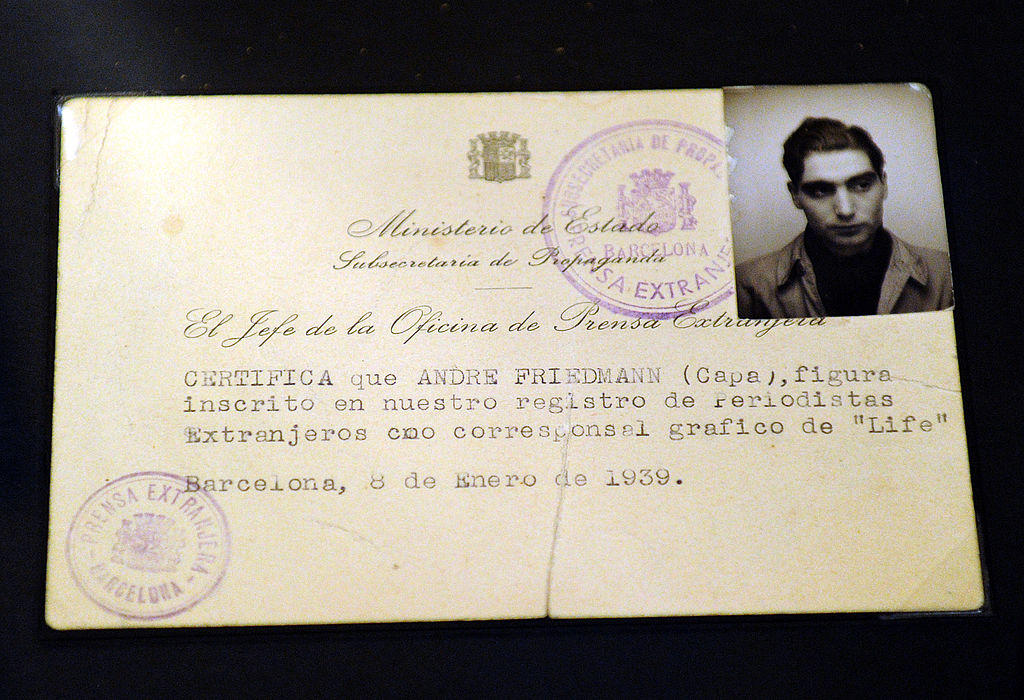

Yeah, I don’t know what I was talking about either. But I went on to suggest we call this new thing Generation X, or Gen X, because that seemed like a catchy title, and Doug Coupland had already stolen it from Billy Idol’s first group, who had taken it from a 1964 book (about youth culture!) of that name by two British journalists, who had maybe/maybe not borrowed it from Robert Capa’s photo-essay of the same title published in Holiday magazine in 1952.

There was precedent, in other words, for using that name as a marker for something you couldn’t quite define.

You can probably guess what happened next: nothing. Not a single person noticed. I didn’t even notice. Back then I forgot what I’d written as soon as I’d written it, and assumed everyone else did the same. The only reason I know I wrote those words is that Rolf Potts, an enterprising writer and podcaster, made a comprehensive search of the available archives on the subject, and found that mine was the earliest reference to Gen X as a generational cognomen, or misnomer, take your Latin-derived pick. But really, so what? You can define cultural movements all day long — these days half the people on social media spend half their time trying to do just that — but there’s no money in it. And if there’s no money in it, nobody cares.

But! It turns out that there is money in marketing to an invented cultural movement. According to a highly-placed source who must remain nameless for mysterious journalism reasons, a woman named Karen Ritchie, who was in charge of marketing for General Motors, gave a speech to a conference of advertising executives later that year and pointed out that these executives – responsible en masse for directing the flow of advertising dollars from corporate America to the pre-atomized media landscape — were missing a huge opportunity in overlooking what she called Gen X.

By the end of 1992, Time magazine was writing in Important Ways about Gen X, Nirvana had caused a kind of moral panic at the disco, Sub Pop had pranked the New York Times about grunge slang, and suddenly everybody knew about this exciting and possibly worrying new phenomenon. As you may have guessed, Gen X was then and has been ever since only ever been useful or interesting as a marketing term.

Here we are, more than thirty years later, getting blamed for everything. Geriatric millennials (kind of clever marketing term) and weirdly entitled Zoomers (“Gen Z,” incredibly lazy marketing term) tell us that our cynicism, our apathy, our rejection of mainstream values and conventional wisdom led directly to the rise of QAnon-and-on conspiracy theories which themselves led to Trumpism, MAGA-try, anti-vax nonsense of every conceivable shape, climate change denialism, and just in general the bipolar divisiveness that now characterizes what remains of the polity, not just here in the U.S. but in places no one’s ever heard of, like France.

Even if there were a seed of truth in that line of thought, “Gen X” the marketing term, the one I inadvertently helped to popularize, only ever applied to a relatively minor wedge of 90s culture, defined if anything by its majority white, middle-class mostly-maleness. It was a blinkered view of things, and like most blinkered views of things, true in part and useless as a diagnostic tool. And even the “true in part” was often untrue: “Bastards of Young,” the Replacements’ Gen X anthem, was written by a boomer. Lollapalooza was invented by a boomer. Generation X, the book, was written by a boomer. Slacker, the movie, was directed by a boomer. All the signposts I had noted as marking a generational shift were the invention of baby boomers.

I’m not saying there isn’t blame to go around here among genuine members of the Gen X cohort (looking at you, Wee Willy Corgan). I’m just saying, hey, the values we espoused may have curdled for a paltry-but-vocal few into a version of frightened nihilism that no sane human could embrace, but that was never our intention. We were just kids. We took what was left to us and we tried to make something out of it.

We weren’t the first generation to fuck it all up, and we won’t be the last.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.