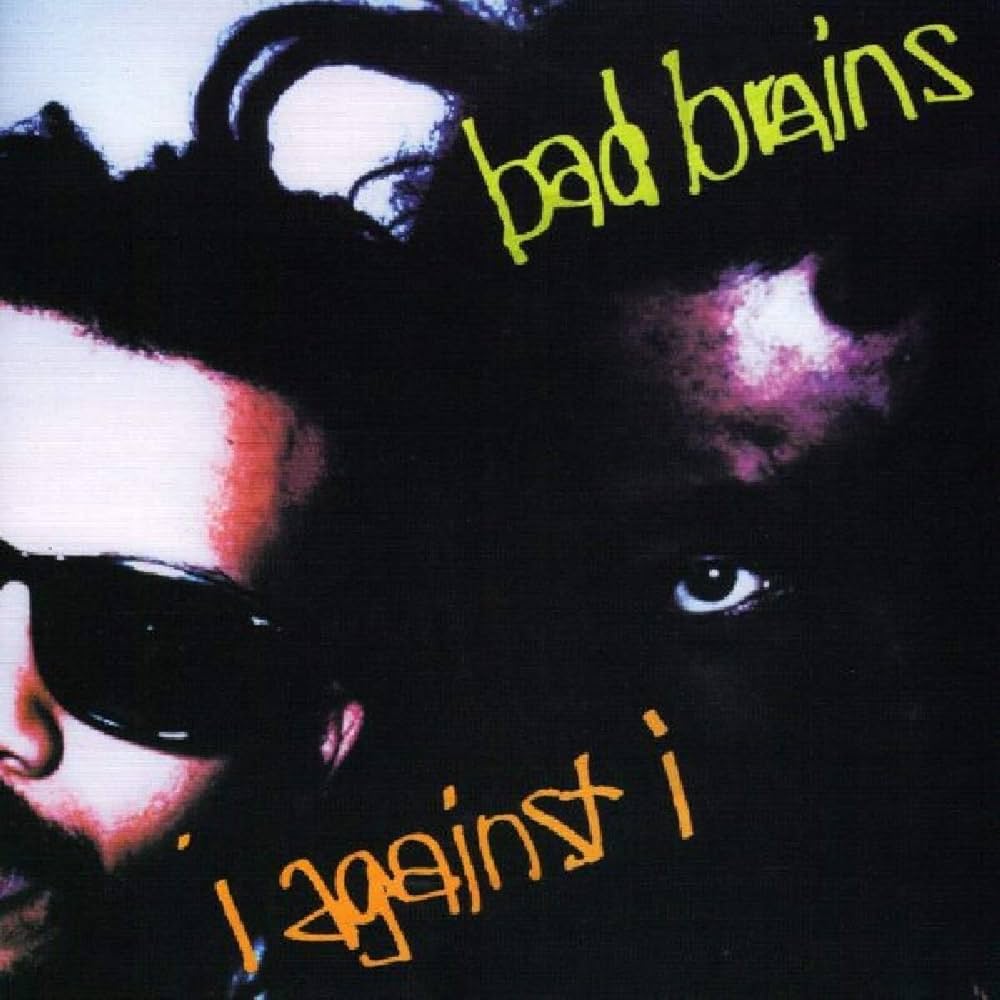

I Against I, Bad Brains

I Against I is the essential Bad Brains document, pushing past the hardcore sound they helped invent into a deliberate mash-up of punk, funk, soul, and metal. On the D.C. act’s third album (and first for SST Records, then at a peak of influence), 10 fiery tracks contrast speed with soulfulness. On the frantic “Let Me Help,” singer Paul “H.R.” Hudson responds with a relaxed vocal about universal peace, while “Secret 77” veers into gothy post-punk. He’s practically Bowie-esque on “Return to Heaven,” as guitarist Dr. Know unfurls one of his many menacing, chaotic solos. Amazingly, virtually all vocals were recorded in a two-hour session of harried inspiration before H.R. had to serve a short prison sentence for marijuana possession. “Sacred Love” was sung over the phone from inside. All of it is the sound of a band peaking under pressure. — Steve Appleford

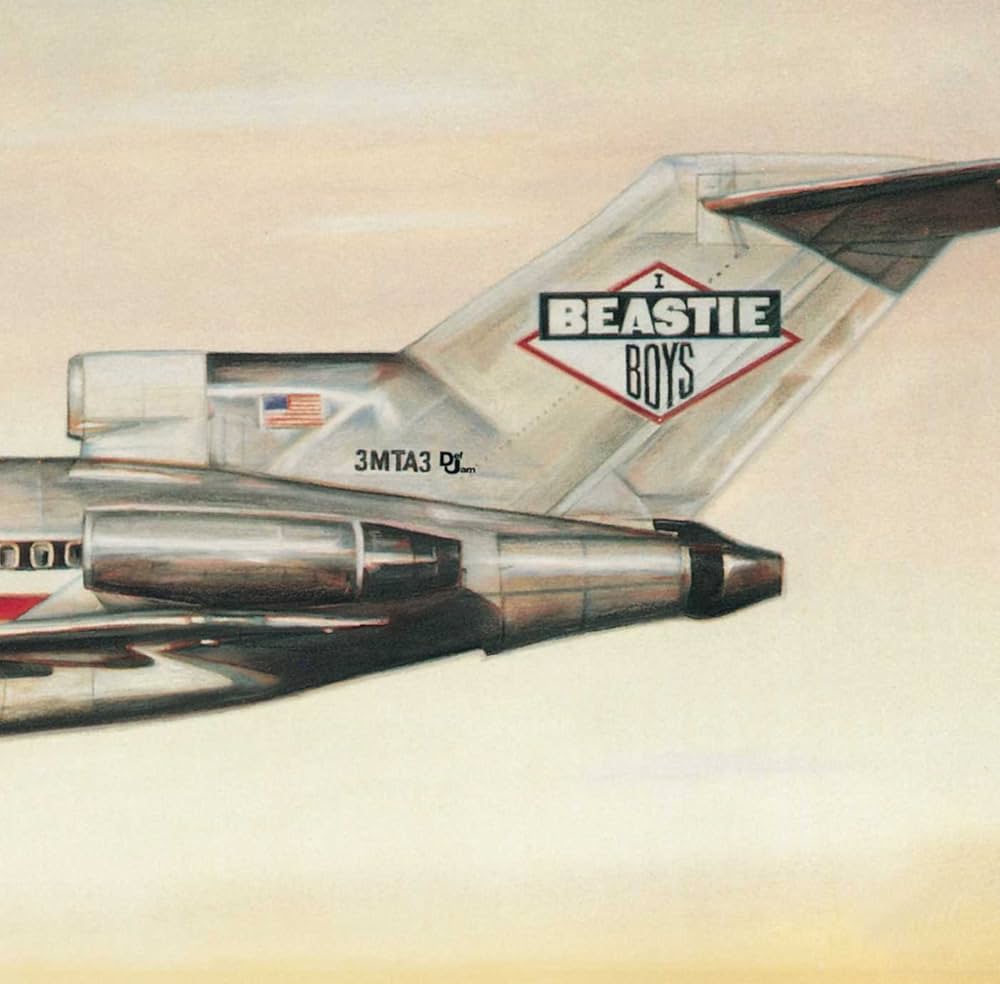

License to Ill, Beastie Boys

Beastie Boys’ pivot from punk rock to hip-hop resulted in Def Jam’s biggest album—Licensed to Ill. Not only was it the first rap album to top the Billboard 200, it was also only the second to earn a platinum certification and among just a handful to reach diamond. Produced by Rick Rubin, the 13-track project opens with “Rhymin’ & Stealin’,” allowing Rubin’s love of classic rock to set the stage with samples of Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks,” Black Sabbath’s “Sweet Leaf,” and The Clash’s “I Fought the Law.” It further married rock and rap on songs like “Fight For Your Right” and “No Sleep Til Brooklyn” (with Slayer’s Kerry King on guitar) then put the art of comedic storytelling front and center on cuts like “Paul Revere.” The latter introduced “the three bad brothers”—Ad-Rock, MCA and Mike D—to a global audience, and eventually launched the motley trio on a massively successful tour. Licensed to Ill wound up being the Beasties only album with the label, but it made history and inadvertently proved hip-hop was for everyone—even frat boys. — Kyle Eustice

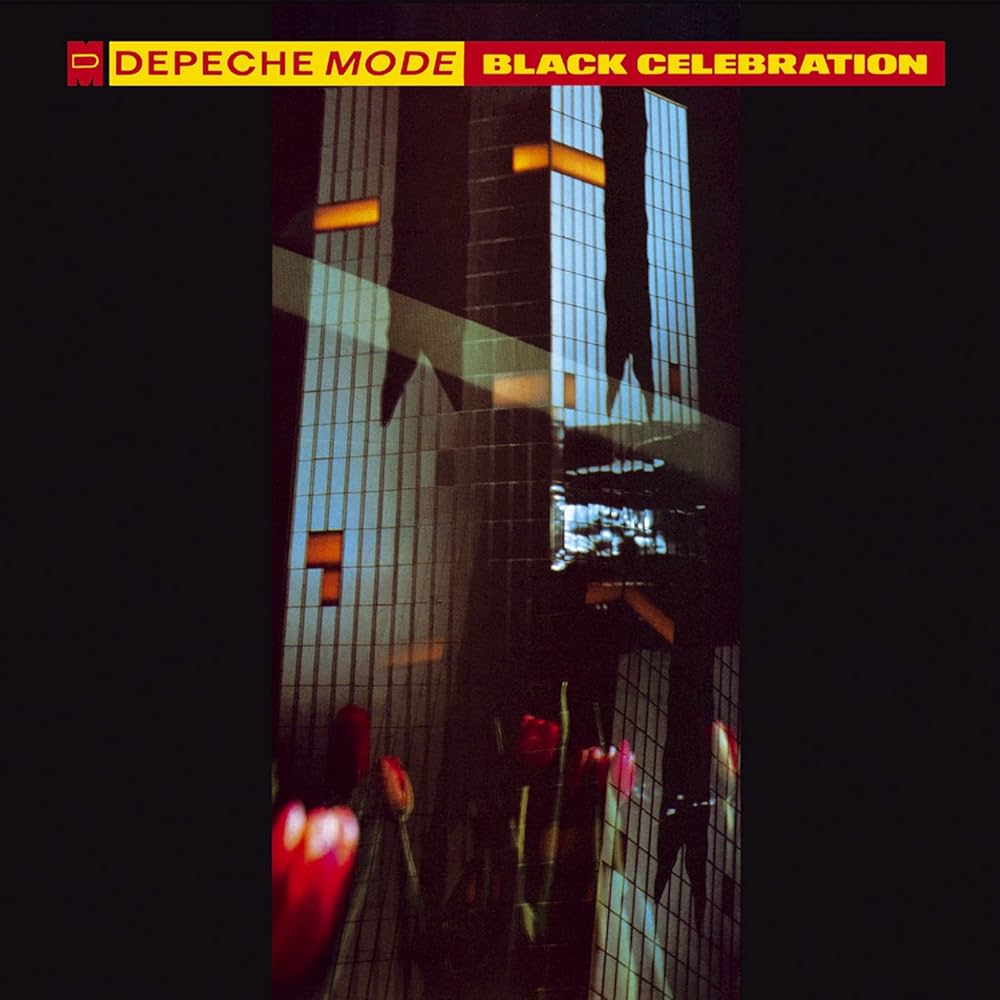

Black Celebration, Depeche Mode

In Depeche Mode chronology, B.C. marks the important divide between all that came before Black Celebration and everything that followed to establish the goth rock saviors. The band’s fifth release (ranked as one of SPIN’s top albums of all-time at one point) was a transitional coup that helped shape the synth-rock pioneers’ signature sound and influenced a score of descendants like Trent Reznor. Emerging at a point of discord for the band, Black Celebration reveled in the internal gloom and resulted in the death of Depeche Mode’s early pop visage. With a sundown on more upbeat numbers like “Just Can’t Get Enough,” the void was filled with more dystopian splendor on “Fly on the Windscreen” and “A Question of Time” and the kinky taboo of “Stripped,” much of it the result of Martin Gore continuing to take on a lion’s share of the songwriting as his tortured poet found a muse in ’80s Berlin. Alongside the steady Alan Wilder, Dave Gahan, and Andy Fletcher, Depeche Mode’s unofficial fifth member—the visual auteur Anton Corbijn—also came on board in this era, helping further mold the massive triptych Music for the Masses, Violator, and Songs of Faith and Devotion that continued the celebration on a larger scale. — Selena Fragassi

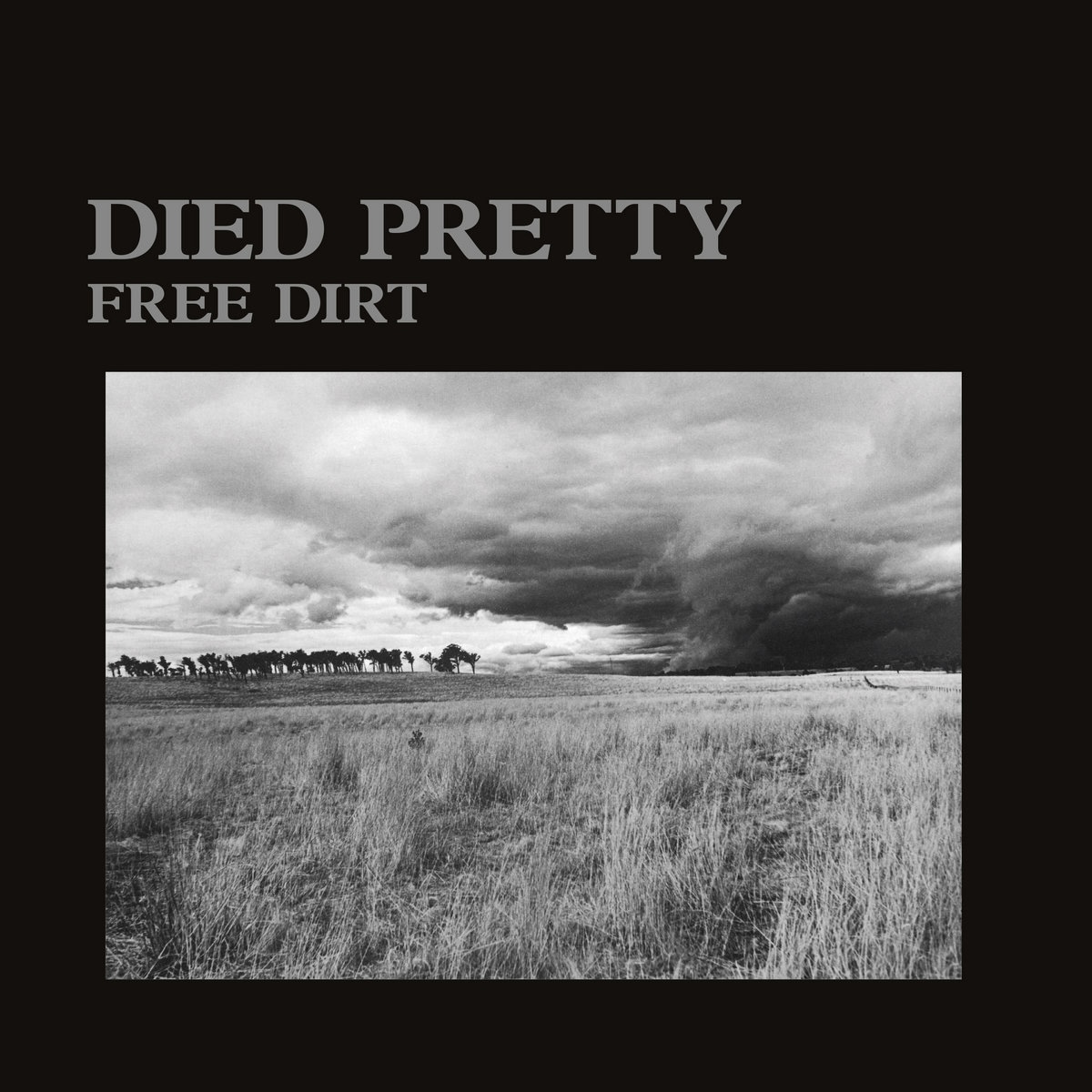

Free Dirt, Died Pretty

If Idiot-era Iggy Pop had somehow ousted pre-OD Jim Morrison from pre-borracho-Doors, he and the band wouldn’t have been as mother-fucking-powerful as Died Pretty in the time of Free Dirt, their searing, scouring, soaring debut LP. How spellbinding it is when Died Pretty’s late mystic mongrel of a frontman, Ron Peno, slowly but thunderously unfurls lines like “I am so happy it scares me to death” as lead guitarist Brett Myers climbs and climbs into the ecstatic crisis of “Just Skin.” Underage I got into their shows again and again as they gigged off this disc in Sydney’s then-thriving pub rock scene, and it was always a passion play: us punters worked into a complex frenzy as Peno, Myers, and Co. remade the world in their spiralling, sweat-drenched, transfiguration of sound. I went backstage at a number of the gigs, scoring a beer or two from their rider, and one time I asked Peno about the sax on Free Dirt—its extreme yet pristine squall—and why their hornman wasn’t playing live. “He went insane,” Peno said. Died Pretty: Accept no substitutes. — Matt Thompson

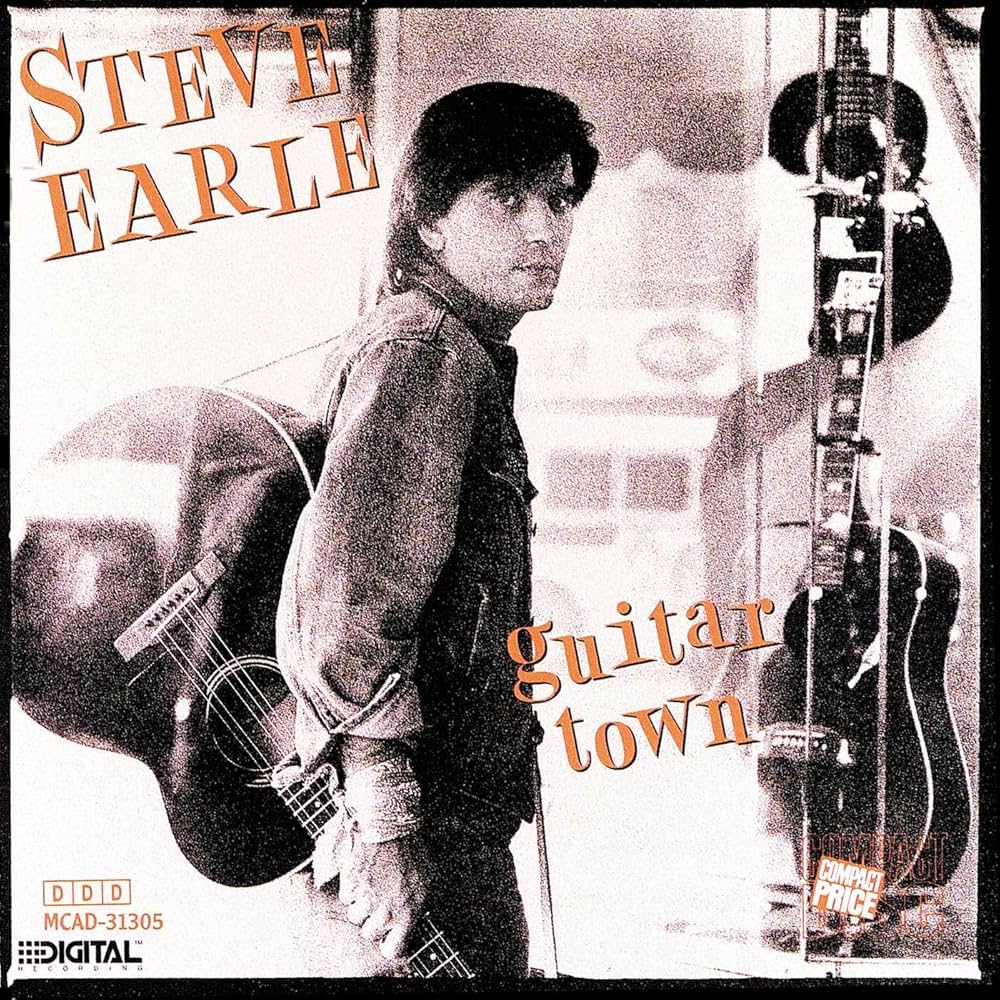

Guitar Town, Steve Earle

1986 was a big year for country music. Just a few months after The New York Times claimed the genre was dying—“Audiences are dwindling, sales of country records are plummeting”—a wave of debuts introduced some new voices and new blood into Nashville. Lyle Lovett, Dwight Yoakam, and Randy Travis all released their first albums during that calendar year, but the most promising freshman appeared to be Steve Earle. He’d already been gigging around Texas and Tennessee for 10 years, so he emerged on Guitar Town with a remarkably strong sense of himself and a good idea of what country could sound like: a little grittier than what was on the radio, a little rougher around the edges, rooted in but not beholden to the past. He writes with the class insights of Springsteen, the rollicking guitars of heartland rock, a twang like rusty barbed wire, and a sense of humor that comes through especially on the road-weary title track (“I got a two-pack habit and motel tan”). Earle wasn’t the future of Nashville, of course, but he remade himself as a bedrock alt-country artist in the 1990s. That makes Guitar Town an outlier in his sprawling catalog: his only real attempt at an establishment album. — Stephen Deusner

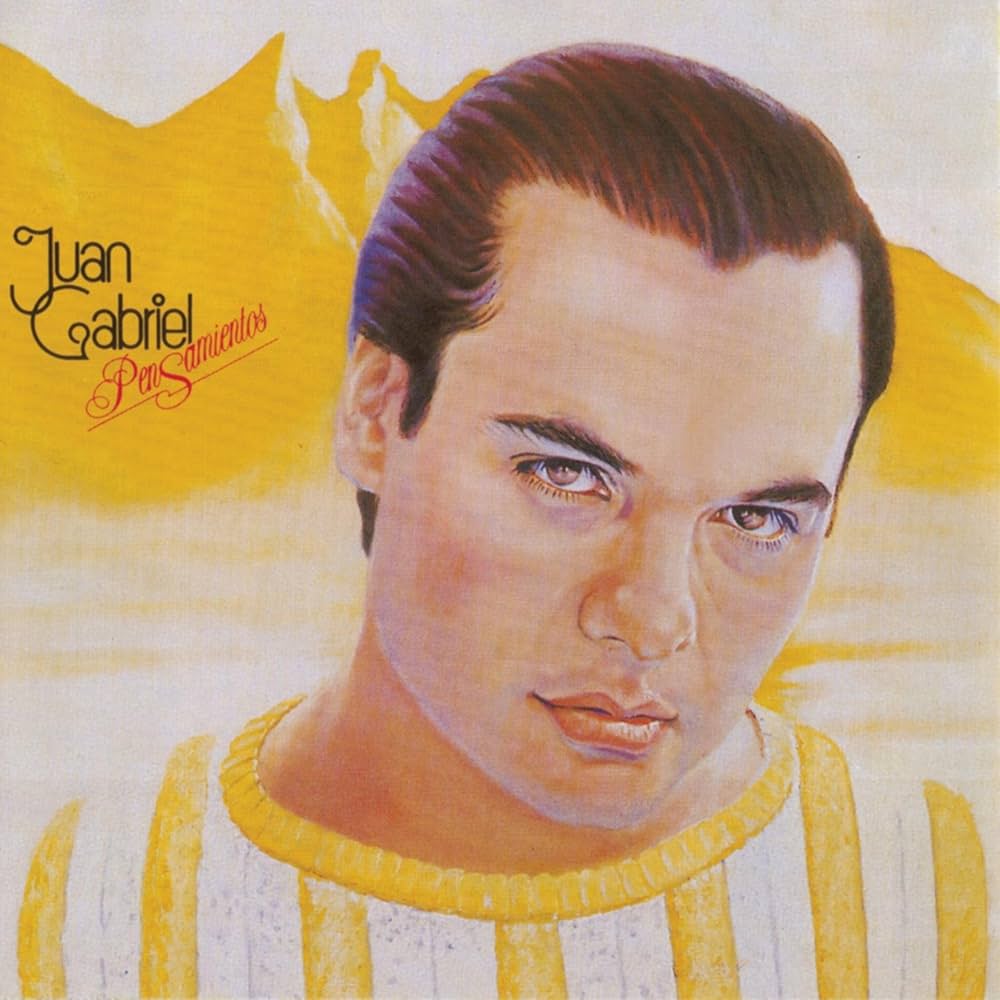

Pensamientos, Juan Gabriel

Juan Gabriel was the backbone of Latin pop music as both a flamboyant performer and prolific songwriter. Before his recording career came to a halt due to a legal battle with his label, the late Mexican star released his most poignant album Pensamientos. Like knowing he would take a nearly decade-long break from the studio, Gabriel pulled at the heartstrings like never before with the haunting “Hasta Que Te Conocí” and his breakup anthem “Yo No Sé Que Me Paso.” He lived up to his “El Divo de Juarez” nickname by temporarily bowing out with the emotional and melodramatic Pensamientos. — Lucas Villa

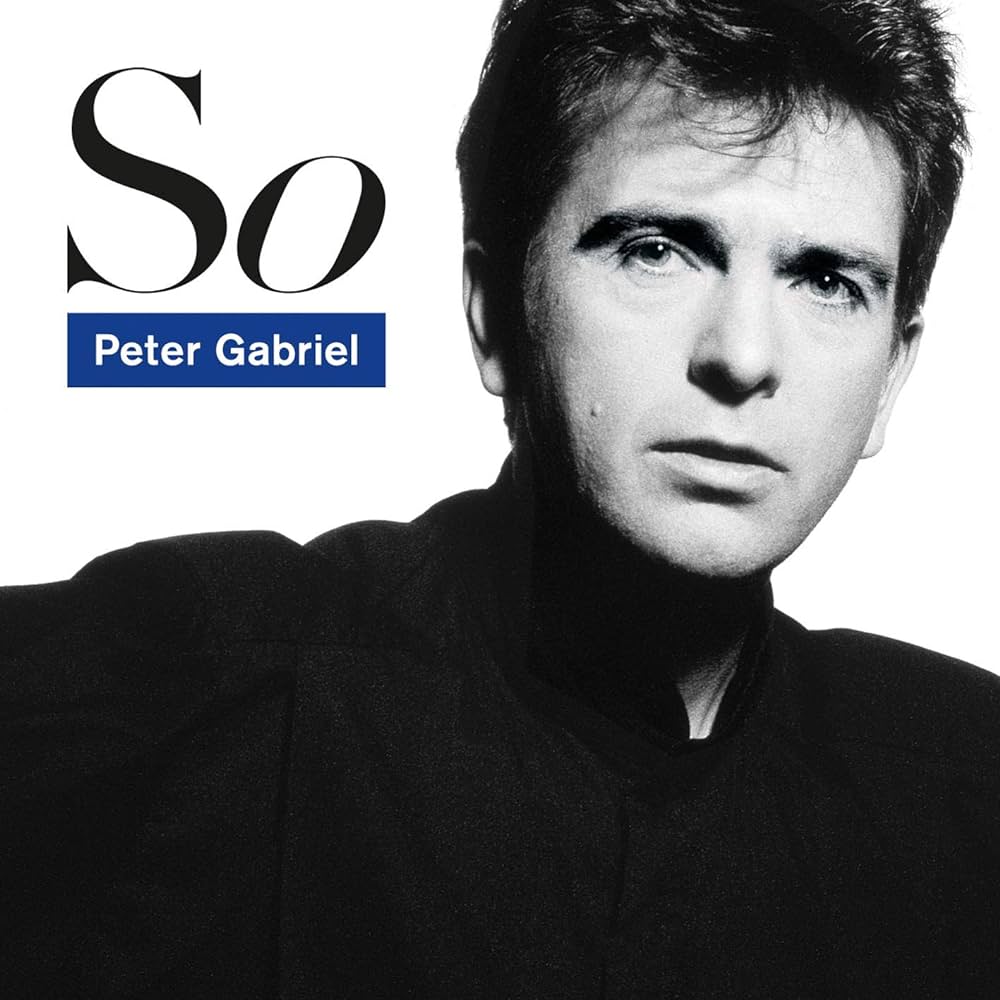

So, Peter Gabriel

There are incredible records—and then there are uncompromised careers. By the time Peter Gabriel released his fifth studio album So in May of ’86— with its first single, “Sledgehammer,” shooting to No. 1 on the Billboard charts, the video winning nine MTV awards—Gabriel had already earned a truly uncompromised, groundbreaking career, and also, with So, proved that he could achieve commercial success. While I’ll always maintain that chart success and artistry will never define a great musician, Gabriel did both. So’s multi-platinum status was aided by his signature exquisite songwriting, from the opening track “Red Rain” to the tear-jerking Kate Bush duet “Don’t Give Up” and the sing-it-loud satire “Big Time.” But it’s the eternally gorgeous “In Your Eyes” that made a permanent heart-soul cultural imprint, unrivaled by any other modern love-story single. — Liza Lentini

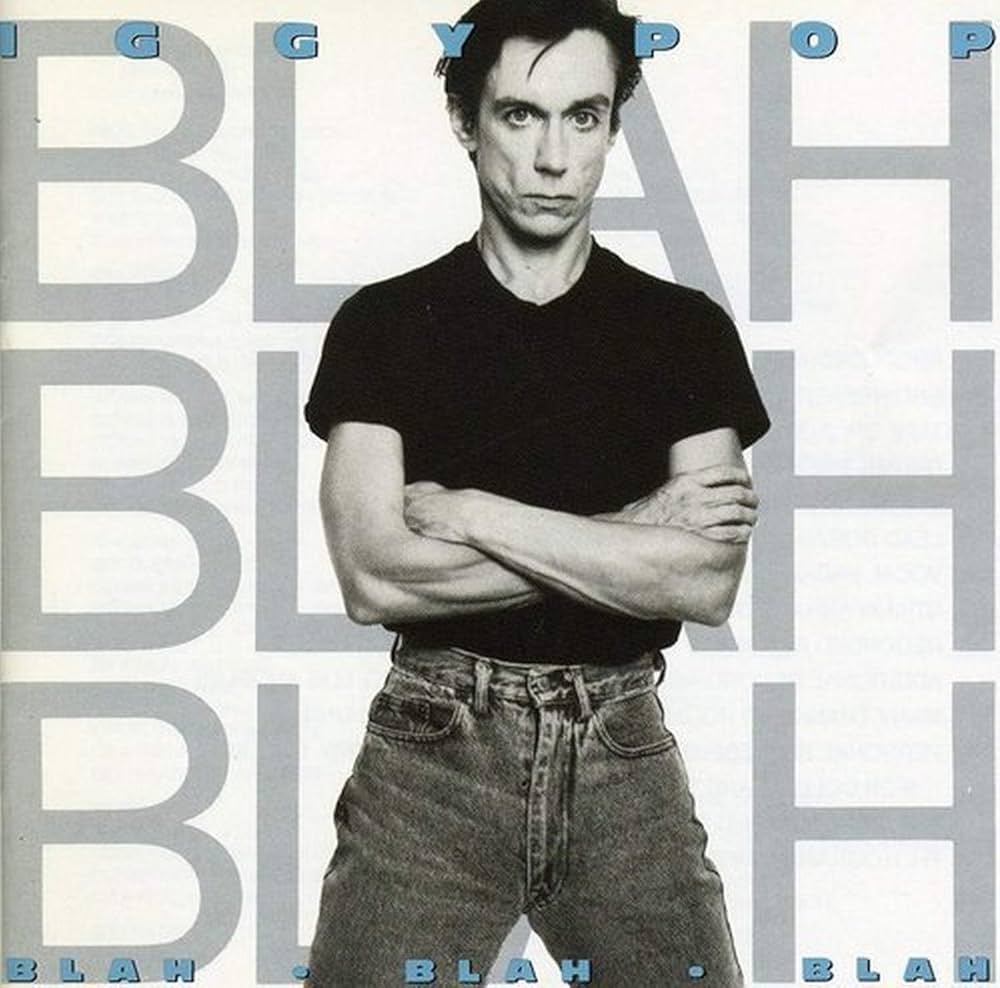

Blah-Blah-Blah, Iggy Pop

Blah-Blah-Blah marked the end of the Bowie-Pop songwriting partnership—a creative alliance that sounds too good to be true. The story goes that Blah-Blah-Blah was just one degree too far into Bowie’s territory of the time for Iggy Pop, and that he basically felt like it was a David Bowie album that he provided vocals for. Now 30 years later, a David Bowie album as told by Iggy Pop doesn’t sound so bad, does it? And while Iggy Pop is known for spearheading punk, the acid-wash ’80s sound suits him. Plenty of his contemporaries burnt out, but Iggy Pop has proven immortal, even on an album so decidedly at home in the ’80s. — Brendan Menapace

Invisible Touch, Genesis

The giant orange hand on the original vinyl cover had a rough, striated texture that mirrored the music inside. On the inner sleeve, a stark black-and-white portrait showed Phil Collins—an unstoppable pop star at this point in the game—leaning affectionately on guitarist Mike Rutherford while keyboardist Tony Banks stood apart, ever the introverted genius. The songs were written from scratch during lengthy jam sessions, and the trio gave themselves permission to be silly and shrill, channeling Motown on the retro ballads and venturing into the staccato ferocity of Simmons electronic drums. The devil is in the details: the gorgeous micro-melodies woven into the first verse of “Domino”; the feverish majesty of “The Brazilian,” a wacky instrumental that encapsulates ’80s excess. Invisible Touch may have sold millions and millions of copies, but its emotional architecture is subversive—and unrepentantly progressive. — Ernesto Lechner

Control, Janet Jackson

The album that turned her from Michael’s baby sister to Janet… Ms. Jackson if you’re nasty. Control finds Jackson breaking from her father’s suffocating managerial grasp and the bubblegum pop of her first two albums to instead collaborate with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis on an innovative collection that synthesized R&B, funk, disco, and rap into what would become Janet’s signature and the foundation of New Jack Swing. Nothing sounded like “When I Think Of You” or “Nasty” in 1986, and they’re still fresh now. But more than that, Control remains a thrilling portrait of a young woman claiming autonomy in the world that’s eager to take it away. — Brendan Hay

The third album from Metallica, the undisputed kings of thrash metal, was their last with bassist Cliff Burton and their first on a major label. The latter did nothing to temper their approach: Master of Puppets delivered some of the most blistering songs of their career, most running at least double jukebox (read: radio-friendly) length. The album sharpens ideas introduced on Kill ’Em All and Ride the Lightning, while leaning into Burton’s instincts for harmony and melody. An undercurrent of fear gives Master of Puppets its relentless grip. Propelled by Kirk Hammett’s shredding guitar work, the album’s eight tracks feel anything but paltry—their force is physical. It was a banner year for thrash, marked by Slayer’s Reign in Blood and Megadeth’s Peace Sells…But Who’s Buying?, but Master of Puppets stood apart, cracking Billboard’s Top 30 and becoming the first metal album preserved in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry—its impact impossible to overstate. — Lily Moayeri

Song X, Pat Metheny and Ornette Coleman

To the uninitiated, the pairing of smoothly eccentric guitarist Pat Metheny and free-jazz firebrand Ornette Coleman evokes that old “Simpsons” joke: “Nuts and Gum: Together at Last!” But the real sickos know that Metheny has a serious avant-garde side, and that Coleman could both rock hard and kill it softly. On Song X, the pair—backed by Charlie Haden (of Coleman’s classic zeitgeist-shifting quartet) on bass, recently departed legend Jack DeJohnette on drums and Coleman’s son Denardo on auxiliary percussion—truly cuts loose, unleashing a staggering barrage of stinging melodies, ecstatic harmonies, whirlpool beats, and dancing rhythms. By turns blistering, beautiful, and bewildering, it looks back to bebop and ahead to noise rock, with pit stops in several other mutant styles (Post-calypso? Dubgrind? Spiritual thrash?) that the world probably still isn’t ready for. — Reed Jackson

Brotherhood, New Order

Sliced in two between disco and rock, the British synth-pop pioneers broke new ground on their fourth studio album. Powered in part by the success of “Bizarre Love Triangle,” which defined dance floors in the ’80s and became a staple of goth raves forevermore, Brotherhood was the album that made New Order more than a Joy Division offshoot band. The ripples of this 10-track masterpiece can still be heard in the work of bands like Brooklyn trio Nation of Language and at parties where leather, all-black, and heavy eye makeup still reign supreme. — E.R. Pulgar

Album, Public Image Ltd.

Decades before anyone used “banger” as a figurative encomium, the producer Bill Laswell hired Tony Williams and Ginger Baker for these sessions and gave us two literal bangers for the price of one. Williams drummed on three tracks, Baker on four, and even now you can’t tell which one is the jazz legend and which one the rock, so primally do both pummel. With a foundation this firm, it would’ve been hard for John Lydon to lose focus, and he didn’t. “Rise” was the hit (in the U.K. and Ireland), and its lyrics — copied and pasted from interrogation-victim testimonies and leavened by an Irish blessing — still cut multiple ways. (Steve Vai’s metallic axework, on display throughout, does too.) But the bangingest bangers are “F.F.F.” (“Farewell, Fairweather Friend” abbreviated to make sure every title was only one word long), “Fishing,” “Bags,” and “Home,” each of which encases Lydon’s legendary bile in an endearingly reverberant thudding. — Arsenio Orteza

Life’s Rich Pageant, R.E.M.

Lifes Rich Pageant came out just two years before Michael Stipe and company made the jump from I.R.S. to Warner Bros., a college radio band growing into a big-label juggernaut. This album is a distillation of what made the band great—fiery rock and roll, a willfully out-of-sequence tracklist on the record sleeve, a cover featuring the drummer’s amazing eyebrows, and a mercurial playfulness that kept the band from taking itself too seriously. It is also home to the group’s finest song—“Fall on Me.” In its lifetime, R.E.M. stood up to three Republican presidents. Now, in this confusing epoch, we need their music more than ever. To quote Stipe quoting Patti Smith on “Just a Touch” “I’m so young, I’m so goddamn young.” Where has all that youthful optimism and opposition gone? And to quote another Lifes Rich Pageant favorite: “This is where they walked, swam / Hunted, danced and sang.” These words felt nostalgic back in 1986. Now, here we are 40 years since Stipe penned those lyrics and they seem even more wistfully distant. — David Harris

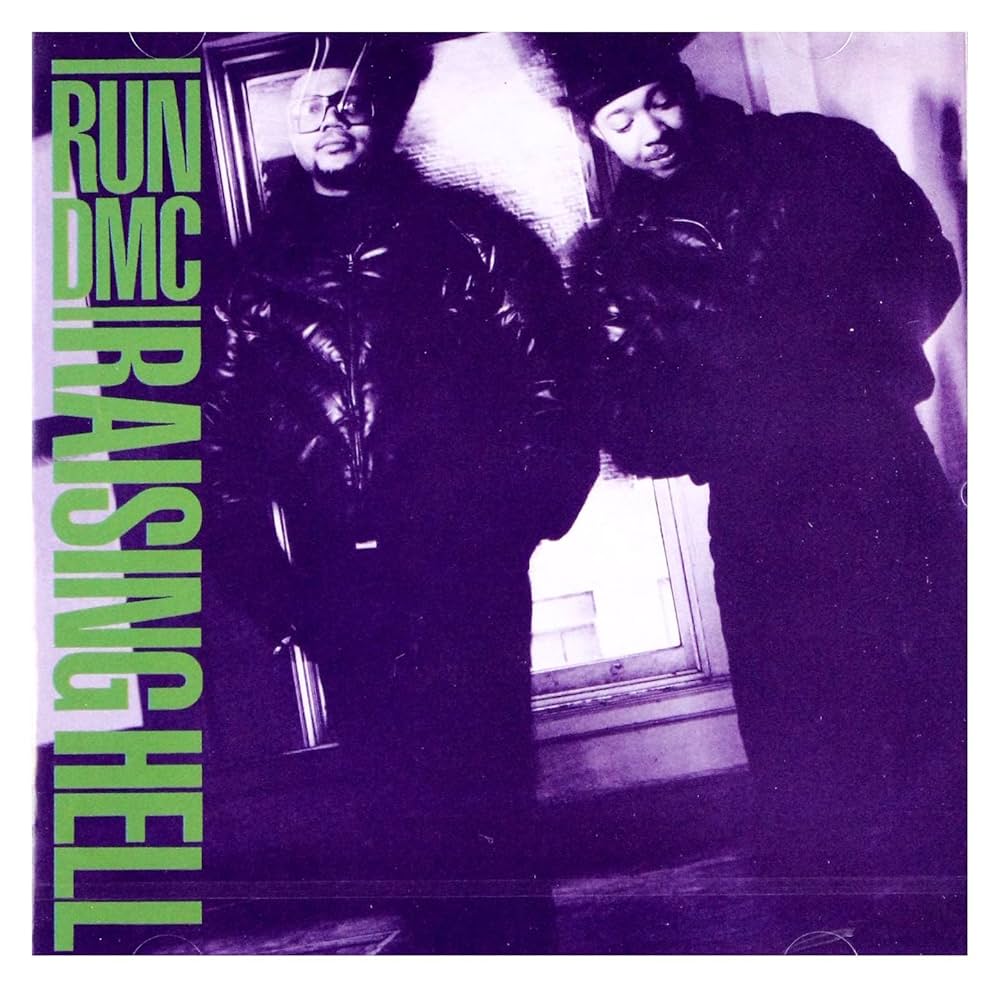

Raising Hell – Run-DMC

Mere months before Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill crashed into music history, Run-DMC’s third studio album, Raising Hell, became the first-ever rap record to sell more than 1 million copies. Produced by Def Jam’s Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons, the project—anchored by four hit singles “My Adidas,” “Walk This Way” featuring Aerosmith, ”You Be Illin’” and “It’s Tricky”—peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard 200. Raising Hell became the first rap album to receive a Grammy nom and is preserved in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress. Not too bad for three kids from Hollis, Queens. —Kyle Eustice

Graceland, Paul Simon

It had been five years since Simon and Garfunkel reunited for the massively successful The Concert in Central Park, and Paul Simon needed a win. The free concert, which amassed more than 500,000 people, was a sore reminder of the magic that was lost when the duo split up in 1970. Simon, whose two previous solo albums, One-Trick Pony and Hearts and Bones, were commercial flops, was going through a depression. He was in his 40s, still recovering from his divorce from Carrie Fisher two years earlier, and questioning his musical direction when songwriter Heidi Berg introduced him to mbaqanga, a style of South African street music. Hearing the blend of traditional Zulu rhythms and harmonies, jazz, R&B, and Kwela, Simon reinvented himself with Graceland, the most successful solo album of his career, spawning now-classic hits like “The Boy in the Bubble,” “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” and, perhaps, most famously, “You Can Call Me Al,” with an assist from longtime asshole Chevy Chase, who guest starred in the music video. — Charles Moss

Reign in Blood, Slayer

For rock fans, 1986 marked a brutal awakening to both the power and the accessibility of heavy music—and Reign in Blood was the sonic assault that hit hardest and left the biggest mark. Maybe the greatest thrash album of all time (some give the title to Metallica’s Master of Puppets), it was definitely the darkest thanks to its creepy satanic cover and sadistic lyricism. Slayer’s third album was precisely what the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center) warned fearful families about in the 1980s, which made its immersive gloom and ominous rhythmic heft all the more intoxicating, especially during hair metal’s hedonist MTV heyday. Coming in at under 29 minutes, the Rick Rubin-produced release marked a raucous new relevance for Def Jam Records and the California band itself, while its unrelenting speed and raw instrumentalism made for a glorious gush of noise that continues to reflect Gen X rebellion (and rage) to this day. — Lina Lecaro

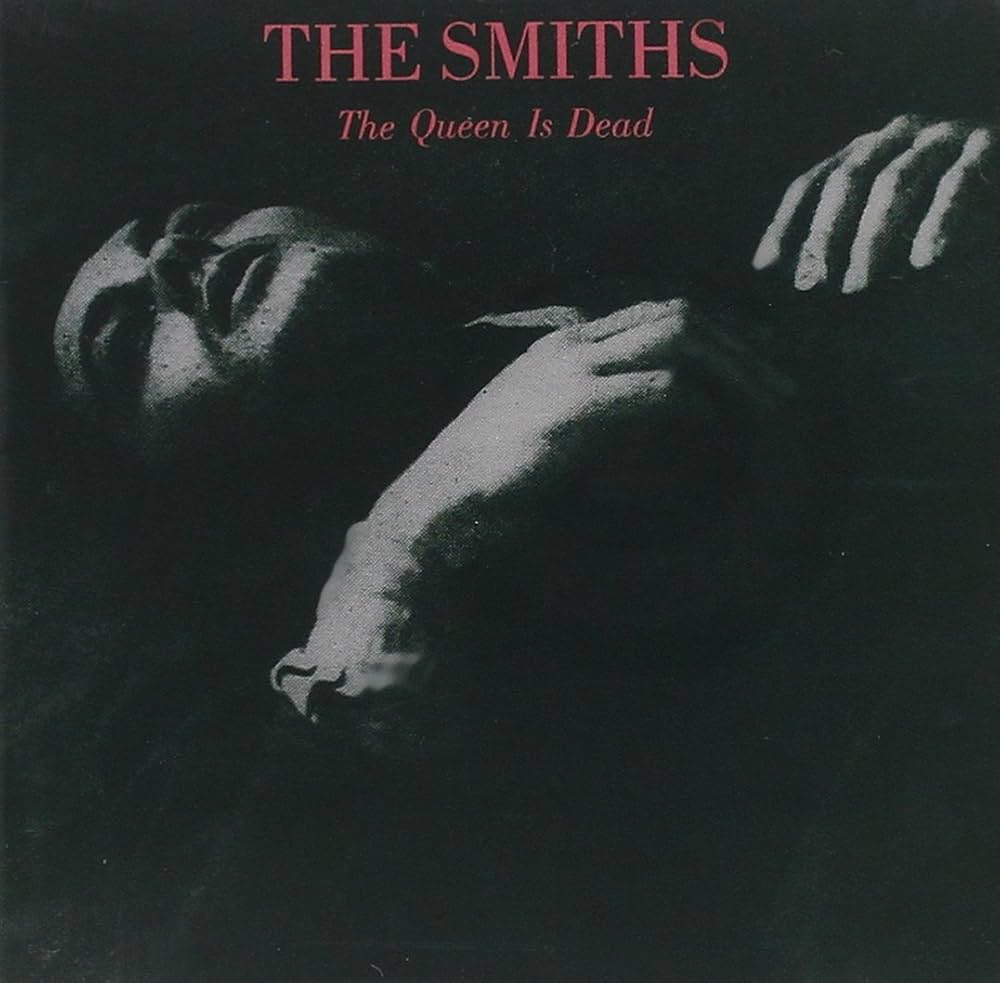

The Queen is Dead, The Smiths

It’s a forever argument whether The Queen Is Dead or Meat Is Murder is the Smiths’ defining album. What’s indisputable, four decades on, is the singular force of the Morrissey–Johnny Marr partnership. The band’s third album—produced by the pair and the last they would ever play live—emerged in a flurry of creativity, combining Morrissey’s cutting, self-lacerating wit with broader indictments of England itself. Marr wove ’70s American influences (Iggy and the Stooges, the New York Dolls) into his guitar work, while Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce’s irreplicable rhythm section anchored adventurous studio experimentation, particularly on “Bigmouth Strikes Again,” “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others,” and the title track. A slow-burn hit in the U.S., eventually going platinum, The Queen Is Dead remains vital, flawless, and endlessly influential. — Lily Moayeri