EXCLUSIVE: After clinching the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2019 with her debut fiction feature Atlantics, French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop had one burning desire.

“My dream was to set up a film school in Dakar,” she tells Deadline.

Diop made history that year in Cannes as the first Black woman to compete in the festival’s official competition. She clocked a similar milestone in February when she became the first Black filmmaker to win Berlin’s Golden Bear with the inventive documentary Dahomey.

Borrowing its name from the ancient West African kingdom of Dahomey, located in the south of today’s Republic of Benin, the doc opens in November 2021 as twenty-six royal treasures from the former Kingdom are about to leave Paris to return to their country of origin. Along with thousands of others, the artifacts were plundered by French colonial troops in 1892.

Dahomey is Diop’s second feature project and the first from Fanta Sy, the Dakar-based production house she quietly launched earlier this year with her creative partner Fabacary Assymby Coly, a Senegalese industry veteran. The company is the result of Diop’s initial film school ambitions.

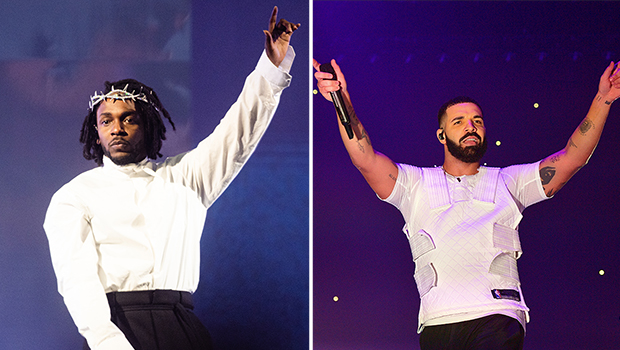

Fabacary Assymby Coly and Mati Diop with their ‘Dahomey’ producers Eve Robin and Judith Lou Lévy (Photo by Andreas Rentz/Getty Images).

“The idea is also to use my network to help the films we support be shown in festivals and distributed around the world,” she says.

Very little information has been published about the company and its strategy — until now. Below, Diop and Coly speak with us about why they decided to launch Fanta Sy, the company’s goals, the projects they’re interested in making, and how they plan to support a new generation of “daring” African stories.

DEADLINE: The name Fanta Sy. What does it mean and why did you choose it?

MATI DIOP: I chose the name the same way I usually find the title of a film. A title should announce the color and evoke a story. Fanta Sy has many inspirations. First, it’s a nod to “Anna Sanders Films,” the first producers who trusted and supported me when I made my first short film in Dakar (Atlantics, 2009). Fanta Sy also comes from an African name I’m particularly fond of: “Fanta,” made world-famous by Alpha Blondy’s magnificent 80s song “Fanta Diallo.” Fanta is also the first name of one of the characters in Atlantique. I’m guessing the surname “Sy” rings a bell. It’s funny to think it is also the name of one of the most popular French actors, though it is typically West African. Fanta Sy is also “Fantasy,” which suggests a particular sensitivity to genre. Whether real or fictional, we’d like to encourage films that carry a vision and assume a formal ambition.

DEADLINE: Mati and Fabacary, how did you first meet?

FABACARY ASSYMBY COLY: I can’t remember. Lol

DIOP: Me neither, which probably means we’ve been working together for a long time. Our first collaboration dates back to 2012 when Fabacary and I managed the entire preparation of my film Mille Soleils (A Thousand Suns) together. As the writer and director, I was very much involved in the production. Fabacary held several positions: production manager and assistant director. Our collaboration worked well and was fluid.

DEADLINE: And where did you get the idea of setting up a production company?

COLY: After Atlantics won the Cannes Prize in 2019, Mati expressed the desire to share her experience and support young Senegalese and, more broadly, African authors. I was already doing this in Senegal but in a very informal way. We started thinking about it and came up with the idea of setting up a company to carry out our ambitions.

DIOP: Initially, my dream was to set up a film school in Dakar. This desire came from the same place as my intention to engage my cinema in this territory, which I’ve been doing since 2008 and to which I’ve devoted all my time so far. Making films, founding a school, and setting up a company are not the same thing, but as far as I’m concerned, it all stems from the same desire to pass on the message. The idea is also to use my network to help the films we support be shown in festivals and distributed around the world. After Atlantics, where Fabacary served as an artistic collaborator, I began to see him as a potential producer of my next films in Senegal. I also decided to become a co-producer on my films.

DEADLINE: Fabacary, people will know Mati more internationally thanks to her work. What is your background and how did you end up here?

COLY: After completing an audiovisual training course in Dakar in 1998, I took several workshops in shooting, directing, and scriptwriting. For the past twenty years, in addition to directing my own films (3), I have worked with several authors on their projects as cinematographer, 1st assistant director, production manager, and producer.

DIOP: I like the story our different backgrounds tell. Fabacary is a key player in Senegalese cinema, embodying local know-how. I embody another reality of Senegalese cinema, which has succeeded in establishing itself on the world stage. This proves to young people that films conceived and shot locally can exist, in their own language, and have legitimacy in this world.

DEADLINE: Is the company based in Dakar?

DIOP: Absolutely.

DEADLINE: What are the company’s objectives? What projects would you like to carry out?

COLY: The aim is to identify young authors through writing workshops, and to support them in the making of their films.

DEADLINE: Mati, in an Instagram post, you said that the company will aim to highlight “the emergence of new filmic writing” from the African continent. What does that mean?

DIOP: That means thinking outside the box, reinventing ourselves, and daring to explore new horizons. Above all, the idea is to listen to the uniqueness of each person we work with and to encourage them to forge their own vision.

DEADLINE: What kind of partnerships do you hope to develop as a company? Both on the continent and elsewhere.

COLY: The type of partnership we’re looking for is first and foremost financial and technical support from the Senegalese authorities and organizations that support the film industry so we can give the best possible support to the authors we develop.

DIOP: Of course, we’re also considering international co-productions, as we did on Dahomey with France and Benin.

DEADLINE: What are you not interested in doing?

DIOP: I’m not interested in producing a film in Senegal that tells our stories, but is shot in French or English, without an African main cast. That’s my red line.

What trends are you noticing on the continent at the moment?

COLY:: In Africa, we’re seeing more and more daring stories – political, social, fantastical – that are wildly inventive, and for documentaries, they are often told in the first person. We’re seeing more and more authors documenting history and depicting reality with an aesthetic that’s sophisticated and assertive.