“They’re scared,” says Taylor Sheridan, looking amused as he steps onto his porch and away from a gaggle of publicists huddled inside his house. “They’re scared of what I might say.”

With good reason. The Yellowstone showrunner — who’s gone from an obscure actor to the most prolific writer in Hollywood in about a decade — isn’t known for pulling his punches and, lately, has been at the center of a stampede of dramatic headlines. His flagship show’s star, Kevin Costner, is exiting the series amid anonymous finger-pointing in the press. There have been showrunner shake-ups on two of his other projects — the Sylvester Stallone drama Tulsa King and the upcoming spy thriller Special Ops: Lioness — where Sheridan seized the creative reins. The creator was also the subject of a recent report that suggested he uses his production budgets to pad his pockets. And his lone-wolf writing style irks some of the writers marching in picket lines who are demanding staffing minimums on TV shows.

It’s a helluva lot of debate circling one hitmaker who created his own genre of neo-Western storytelling and whose shows are so popular, they’re propping up an entire streaming service. Over a couple of hours of conversation, Sheridan reveals his side to these stories for the first time while offering unparalleled insight into his writing and producing process.

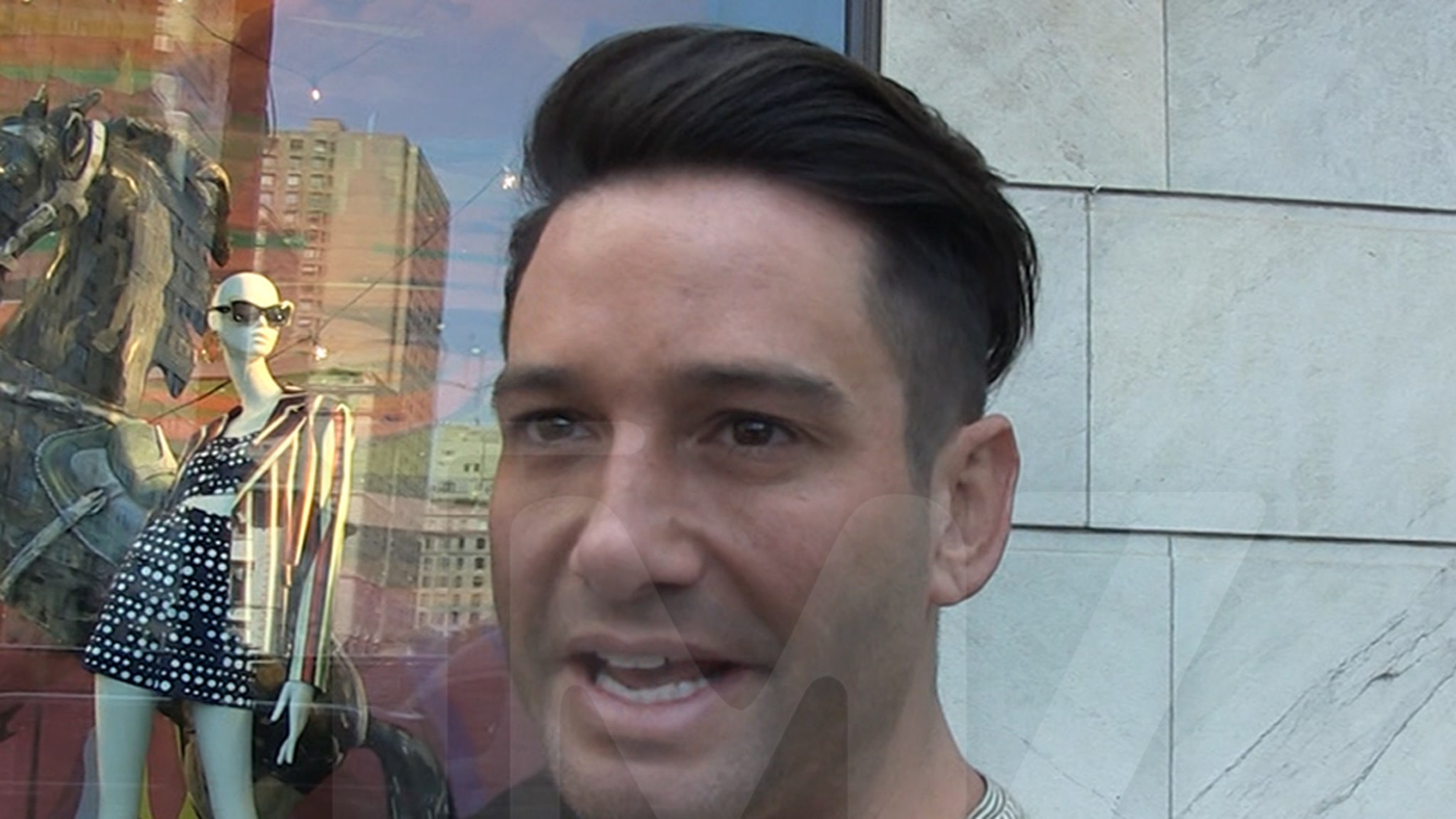

Taylor Sheridan

Photographed by Emerson Miller

Sheridan takes a seat wearing a button-down shirt, rugged jacket, jeans and boots, complete with spurs (he was riding earlier). The 53-year-old is a formidable wall of blue denim, and his eyes are blue, too. Elizabeth Olsen, whom he directed in Wind River, once affectionately described Sheridan as “a cowboy who’s like a combination of your dad and the Marlboro Man.”

We’re sitting behind one of his houses on his massive Four Sixes ranch. The property is wedged up in the remote Texas panhandle, several hours’ drive from the nearest major city. (The Montana ranch in Yellowstone is fictional, but the Four Sixes, or 6666 — which is also featured in the series — is real.) Sheridan finalized his purchase last year, and it covers a staggering 270,000 acres — nearly the size of Los Angeles. Stretching from his porch is a dreamy field of virgin countryside extending to the horizon under cotton-ball clouds. There’s a warm breeze and, every so often, a Texas Longhorn steer trots by.

The importance of this place to Sheridan — and its connection to Yellowstone and to the rest of his TV universe — cannot be overstated. Sheridan grew up in North Texas, where the Four Sixes is legendary. The ranch and its horse-and-cattle operation were long controlled by a single dynastic family that battled for 150 years to protect their land and keep it largely intact. Sounds familiar, right?

“I grew up in the shadow of the Four Sixes,” Sheridan says. “To just get one of their horses was a status symbol, because they’re so well trained. This was the ranch I based [Yellowstone’s] scope and operation on, because it didn’t exist in Montana. Most ranches there had already been carved up. They’d already lost it.”

Acquiring the property, however, wasn’t easy. Sheridan says he renewed his overall deal at Paramount in 2021 and started pumping out prequels and pilots to help pay for all this. It was an extraordinary burst of get-the-ranch productivity that’s resulted in green lights for six series. Yet the amount of work that piled onto Sheridan’s plate as a result, coupled with his own obsessive drive to make every episode bearing his name just right, appeared to have some unforeseen consequences.

But first, let’s appreciate what Sheridan has accomplished, because it’s remarkable and rather strange. Twelve years ago, the struggling actor was down to his last $800 when he sold his first screenplay. He later created a TV show about a man who owns a dynastic mega-ranch who struggles to protect it and make it successful … and its success has allowed Sheridan to himself become a man who owns a dynastic mega-ranch who struggles to protect it and make it successful — and not just any ranch, but the same one that served as the basis for his show. Sheridan dreamed up a story, shared it with millions, and then stepped into it.

“Life imitating art was never my intention,” he says, and quips, “We haven’t killed anyone in weeks.”

Sheridan (who lives with his wife and 12-year-old son) points out that actually he’s been involved with ranching his whole life and previously owned a modest 1,200-acre property. “That was my dream and I already had it,” he says. “It was a great escape from the fact I was a failing actor living in West Hollywood. The plan was always to become a big movie star, then move back to a ranch and just do movies with Martin Scorsese when I felt like it.”

Sheridan laughs at this. “But that wasn’t my path.”

“YOU CAN’T MAKE THIS S—T UP”

“I was a fair actor, but that’s all I was ever going to be,” Sheridan recalls. “Hollywood will tell you what you’re supposed to do if you listen. If you’re banging your head against the wall for 20 years trying to be an actor, maybe you shouldn’t be an actor. But the first thing I ever wrote [the pilot for Mayor of Kingstown in 2011] got me meetings at every major network, at every agency. I had multiple people trying to buy it.”

Yet Sheridan refused to sell. The studios, he says, wanted to hire a room of more experienced writers to tackle the project — you know, make TV the usual way. Sheridan felt that he knew exactly how to write the show himself. So even back then, getting his first taste of success as a writer, Sheridan was reluctant to let others adapt his material and demonstrated a willingness to walk away. Some might call that stubborn or impractical; Sheridan sees it as trusting his instincts and sticking to his creative guns. He put Mayor of Kingstown in a drawer.

Over the next few years, Sheridan made a name for himself writing a trio of acclaimed films — Sicario (2015), Hell or High Water (2016) and Wind River (2017) — which he dubbed his “modern American frontier” trilogy.

Another of his scripts, Yellowstone, was likewise originally written as a movie. Sheridan pitched it as “The Godfather in Montana,” and it ended up in series development at HBO. Sheridan says then-programming president Michael Lombardo was supportive, but the rest of his team wasn’t.

“I thought Taylor was the real deal,” Lombardo says. “In a world of people who pose, he was writing what he knew, and he cared desperately about the show. The idea of doing a modern-classic Western was a great idea — we were always doing urban shows, and this felt fresh.”

The one thing they all agreed on was that Yellowstone needed a big star to play its uncompromising patriarch, John Dutton. Sheridan pitched Costner, but HBO executives “didn’t see it.”

“They said, ‘We want Robert Redford,’ ” Sheridan recalls. “They said, ‘If you can get us Robert Redford, we’ll greenlight the pilot.’ “

Being a can-do type of guy, Sheridan went to visit Robert Redford.

“I drive to Sundance and spend the day with him and he agrees to play John Dutton,” Sheridan says. “I call the senior vice president in charge of production and say, ‘I got him!’ ‘You got who?’ ‘Robert Redford.’ ‘What?!‘ ‘You said if I got Robert Redford, you’d greenlight the show.’ “

“And he says — and you can’t make this shit up — ‘We meant a Robert Redford type.’ ”

A crisis meeting was scheduled with the network vp (“whose name I remember, but I’m just not saying it”) to get to the bottom of HBO’s reluctance.

“We go to lunch in some snazzy place in West L.A.,” Sheridan says. “And [Yellowstone co-creator] John Linson finally asks: ‘Why don’t you want to make it?’ And the vp goes: ‘Look, it just feels so Middle America. We’re HBO, we’re avant-garde, we’re trendsetters. This feels like a step backward. And frankly, I’ve got to be honest, I don’t think anyone should be living out there [in rural Montana]. It should be a park or something.’ “

Sheridan later put some of those lines into Yellowstone‘s season two, when a New York magazine reporter disses Montana to Wes Bentley’s character, Jamie … and then Jamie murders her.

Sheridan, pictured here on the Yellowstone set in 2021.

Courtesy of Paramount Network

The executive’s coastal elite diss convinced Sheridan that HBO didn’t appreciate his story. During a notes call, Sheridan says, executives took issue with Dutton’s ferocious daughter, Beth (Kelly Reilly), who has since become a fan-favorite sensation.

“‘We think she’s too abrasive,’ ” Sheridan quotes. “‘We want to tone her down. Women won’t like her.’ They were wrong, because Beth says the quiet part out loud every time. When someone’s rude to you in a restaurant, or cuts you off in the parking lot, Beth says the thing you wish you’d said.”

Sheridan recalls, “So I said to them, ‘OK, everybody done? Who on this call is responsible for a scripted show that you guys have on the air? Oh, you’re not? Thanks.’ And I hung up. They never called back.”

That should have been the end of the Dutton family. HBO typically retains the rights to scripts it develops and rejects, partly to prevent what happened next from happening — a project they spent time and money developing becoming a global smash for a competitor.

“When the regime changed, Lombardo called me,” Sheridan says about the longtime HBO exec’s exit in 2016. “To his credit, he said, ‘I always believed in the show, but I could not get any support.’ His last act before they fired him was to give me the script back.”

As for that nameless vp, Sheridan says he left HBO and landed a production deal. After Yellowstone took off, he emailed Sheridan to say congratulations — and to pitch him a family drama.

Sheridan says he wrote back: “Great idea. It sounds just like Yellowstone.”

“I WAS REAL RICH FOR 45 MINUTES”

After coming up empty at HBO, Sheridan shopped Yellowstone around town. Everyone, he says, turned it down (“I took it to TNT … I took it to TBS!” he marvels). When Paramount finally bit, Sheridan bluntly warned executives they were going to spend a ton of money on production and would not have any creative control.

In 2018, Yellowstone debuted on the company’s niche cable channel, the Paramount Network. Within a few years, ratings exploded. “People couldn’t understand how a linear cable channel that no one can even find suddenly had the biggest show on television,” Sheridan says. “Because it has cowboys and this is supposed to be a dead genre, right? Of course, that’s not what the show is really about, that’s just the sugar on the pill.”

What Yellowstone is really about is a dying American way of life, a clash between traditions that respect the land and the unstoppable intrusion of modernity. Yet by the time he was making season three, Sheridan was starting to worry that his not-so-secret mission to save ranches in real life was doomed.

“I thought I had tricked people by showing a world worth protecting,” he says. “But when the show is over, that notion will go away and there will be a new shiny penny everyone watches. So I felt like I didn’t accomplish anything — which, for me, is really important. Sicario is entertaining, but it’s about something: the jumbled mess at the border.”

Sheridan went to the Four Sixes in late 2019 and pitched its then-owner, 81-year-old Anne Marion, on the idea of introducing her ranch into Yellowstone with a few scenes. He pledged to make the Four Sixes “the most famous ranch in America.”

Burnett asked if there would be any sex in the Four Sixes footage. “I said, ‘Well, one cowboy is sleeping with a vet tech, but don’t tell me that’s not happening already.’”

“And,’” Sheridan told her. “I would like to masturbate one stallion.”

Ms. Marion agreed, so long as she could pick the stallion.

Sheridan says this with a straight face and one tries not to snicker. This is normal life-on-the–ranch stuff, and it all ended up in Yellowstone (actor Jefferson White, who plays Jimmy, got the stallion honors).

Then, a couple of months later, a turn of fate: Burnett died and Sheridan received a call from the estate. The ranch was going up for sale, and might have been broken into pieces — the exact fate the Dutton family is always fighting to prevent. They offered Sheridan a chance to purchase the property.

“I said, ‘How much?’ They said, ‘It’s $350 million.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m about 330 short. But please, you thought enough to call me, will you give me two weeks?’ “

Sheridan says the opportunity changed his mind about expanding his overall deal with Paramount Global (then ViacomCBS). He valued his independence, preferring to be “a hired gun.” But to buy the ranch, he signed a new contract reportedly worth $200 million and wrangled some additional investors to bridge the gap.

“I was real rich for 45 minutes,” he says. “Then I was broke again. That was the trade.”

I give Sheridan a hypothetical: Your TV shows and your ranch are both hanging off a cliff. Which do you save?

“I do the shows for the ranch,” Sheridan says firmly.

But in trying to make so many shows so fast, didn’t you take on too much?

“I’ll tell you what,” Sheridan says. “It sure looked that way.”

“THERE IS NO COMPROMISING”

“The plan was I would Greg Berlanti it,” Sheridan says, referring to the prolific producer of The CW’s DC Universe shows. “I would write, cast and direct the pilots, and then we would bring in someone as a showrunner to run a writers room and I could check in and guide them.

“That plan failed,” he says. “There were some things that none of us foresaw.”

One of those is that, in Sheridan’s opinion, the writers hired for Tulsa King and the upcoming Lioness (which stars Zoe Saldaña, Morgan Freeman and Nicole Kidman) didn’t work out.

“My stories have a very simple plot that is driven by the characters as opposed to characters driven by a plot — the antithesis of the way television is normally modeled,” Sheridan says. “I’m really interested in the dirty of the relationships in literally every scene. But when you hire a room that may not be motivated by those same qualities — and a writer always wants to take ownership of something they’re writing — and I give this directive and they’re not feeling it, then they’re going to come up with their own qualities. So for me, writers rooms, they haven’t worked.”

Of course, Sheridan could have let it slide. Tulsa King’s showrunner was Terence Winter (who declined to comment), the four-time Emmy winner who wrote The Wolf of Wall Street and created Boardwalk Empire. Why not empower writers to take his shows in their own direction? You know, compromise.

“I spent the first 37 years of my life compromising,” Sheridan shoots back. “When I quit acting, I decided that I am going to tell my stories my way, period. If you don’t want me to tell them, fine. Give them back and I’ll find someone who does — or I won’t, and then I’ll read them in some freaking dinner theater. But I won’t compromise. There is no compromising.”

Sheridan hesitates. Maybe that’s too strong? “There is compromising on things like budget,” he adds, but then again maybe not. “You write a thing and it costs what it costs. I will not change a script to meet a budget. You read the scene [in his Yellowstone prequel 1883] where the wagons go across the river when you decided to green light it. So don’t pitch me an idea where we see them before the river and after the river. That’s not what I do. You read it, you had every chance to say no.”

This is where things get slippery in terms of pinning down Sheridan’s motives. The man says he makes shows to support his ranch, but he can’t help but care about his shows too. A lot. “I get paid whether they’re good or bad, but that’s not really winning,” he says. “’I’m one of those people that’s incapable doing something that’s not tethered to 100 percent of my passion. I cannot do ‘OK’ at a job.”

From left: Isabel May, who plays Elsa Dutton on 1883, with Sheridan.

Courtesy of Paramount Network

So Sheridan booted Winter as showrunner on Tulsa King and also started writing Lioness episodes himself — just as he writes all the episodes in the Yellowstone franchise (after early attempts at collaborating with others on that show, too). “If you don’t grow up in this [ranching] world, and if you’re not a history fanatic, how do you write 1883?” he asks. “How does a room do that? It doesn’t.”

Paramount Media Networks president and CEO chief Chris McCarthy says Sheridan is always welcome to be more hands-on. “You can’t teach or hope that someone cares more than Taylor,” he says. “So anytime that he wants to step in, it’s only to make it better and to push our partners to achieve greatness.”

The studio is seeking a new showrunner to take on the second season of Tulsa King (presumably, a very talented writer with modest job security expectations).

There are a couple of other showrunners (like White Lotus creator Mike White) who likewise prefer to write entire seasons solo, though it’s a stance that has been under scrutiny as it bumps up against the WGA’s efforts to convince studios to hire a minimum number of writers for each scripted show.

“The freedom of the artist to create must be unfettered,” Sheridan counters. “If they tell me, ‘You’re going to have to write a check for $540,000 to four people to sit in a room that you never have to meet,’ then that’s between the studio and the guild. But if I have to check in creatively with others for a story I’ve wholly built in my brain, that would probably be the end of me telling TV stories.”

Sheridan often writes in a one-room “cabinet” he built in Wyoming. He was always a fast writer, he says, but after building his script-generating isolation bunker, he was suddenly able to grind out episodes of hit TV shows at a phenomenal speed.

“I’ve written many episodes in eight to 10 hours,” he claims.

Does Paramount ever give you notes?

“No, sir.”

Do you ever watch an episode and think that you should have spent more time on it?

“No.”

And the script starts and ends with you? They go straight to the actors?

Sheridan considers this for a moment.

“They tell me there’s a story coordinator,” he says, “but I don’t know who that is.”

(Somewhere, a Yellowstone story coordinator reads this and sadly hangs their head.)

“Taylor writes scripts like you or I have a cup of coffee,” says Sheridan’s producing partner David Glasser. “He’s written 60 scripts for Yellowstone — most people don’t do that their entire career. It’s because of his excitement for the material.”

Living and working on a ranch has given Sheridan a creative edge, too. “When I lived in Los Angeles, everything I saw was the same and I didn’t learn anything in my day-to-day life,” Sheridan says. “Here, I get to experience so much. I heard 25 iconic pieces of dialogue today. Most of my great lines I heard someone else say, or some version of it. I’m banking story all the time.”

By early 2021, Sheridan was writing, producing and directing, cranking out ideas and episodes for multiple projects. Then, in April, Sheridan received a game-changing call from Paramount. The studio’s parent company had made an early blunder by selling the streaming rights to Yellowstone to Peacock. But they could stream a Yellowstone prequel series, and executives were excited by Sheridan’s pilot script for 1883.

“They say: ‘We’re changing everything! We’re launching this on our streaming service.’ And the first thing I said was: ‘You guys have a streaming service?’ They said, ‘Yeah, and we need this show.’ “

Paramount wanted Sheridan’s wagon train epic on Paramount+ by the end of the year. This was “impossible,” Sheridan says. He was prepping to direct two episodes of Mayor of Kingstown (he sold his shelved script to Paramount in 2020), and 1883 was going to require hands-on attention. “With this schedule, I’m in production on episode six on the day episode six is supposed to air,” he says. “How are we going to do that? Let’s pretend like we do this for a living.”

So Sheridan came back with a proposal.

“We’re going to shoot six-day weeks, sometimes seven,” he recalls telling the studio. “I’m going to bring on two other directors, but I’m still going to direct on every episode. I’ll bring in everyone myself. I’ll use as much local crew as I can, but I need the very best. I need an editorial team who’ll work 24 hours a day. You’ve got to get a VFX house and lock ’em down because every shot is an effects shot [to erase modern details]. And I don’t want to have one budget meeting, because you are now paying the ‘oh shit’ rate.”

Sheridan says this is an example of why his productions use assets he owns, or crew he’s close to, even when cheaper options might be available — he claims each decision is made for reasons of safety, convenience or competence under tight deadlines. Yet a recent Wall Street Journal report quoted production staffers expressing concern over excessive spending in leaked emails. The story followed Paramount’s $511 million first quarter loss in its streaming business even as Sheridan’s shows have been credited with adding millions of subscribers.

“It’s not double dipping,” Glasser contends. “Everything we do has a three-bid system, and Viacom has an audit team. Like shooting 1883 on Taylor’s ranch [for a reported $50,000 a week] was at a comparable price to the ranch next door. We rent a lot of ranches and know how much they cost.”

Another example: Sheridan says he uses his own horses because they can be relied upon to keep filming on track and have been trained to handle actors.

“They gave me a budget of $175 million [for 1883],” Sheridan says. “I thought it was going to be $225 with the rush costs. We did it for $169. And it was the biggest show.”

Sheridan looks proud of this, and with good cause. The premiere of 1883 drew 8 million viewers for the Paramount Network — the biggest cable TV debut in more than six years. Its availability on Paramount+ helped put the streamer on the map, and it opened a new franchise of Dutton family prequel shows. A success on every level.

There was just one thing.

With Sheridan jamming to pull off 1883, another project that also required his full attention had to be delayed: Yellowstone season five.

“I DON’T DO ‘F–K-YOU CAR CRASHES’”

Earlier this year, Costner shocked the Yellowstone-verse by deciding he wanted to exit the series. Paramount has since confirmed that the show will end with the upcoming second half of its fifth season.

Costner is leaving to focus on his own Western epic, a four-movie saga titled Horizon that he’s co-writing, directing and starring in. The actor had been trying to get Horizon made for 35 years and is expected to wrap the second film this week. Costner (who declined to comment for this story) has said the first installment might premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September.

The actor requested to work fewer and fewer days on Yellowstone the last few seasons to focus on his movies, which frustrated producers. Yet one source insists Costner kept “waiting on scripts” and that he repeatedly blocked out time to shoot, only to see his dates pushed. “Kevin’s been unfairly portrayed in this thing,” the source says. “How can you schedule something when there are no scripts? [Sheridan’s] doing eight other shows.”

Says Sheridan: “My last conversation with Kevin was that he had this passion project he wanted to direct. He and the network were arguing about when he could be done with Yellowstone. I said, ‘We can certainly work a schedule toward [his preferred exit date],’ which we did.”

There are ongoing discussions to try to convince Costner to film a few scenes to wrap his character, though the scripts are not yet complete. One would think Dutton having final conversations with his warring kids, Beth and Jamie, would be particularly helpful to set up the show’s home stretch.

“My opinion of Kevin as an actor hasn’t altered,” Sheridan says. “His creation of John Dutton is symbolic and powerful … and I’ve never had an issue with Kevin that he and I couldn’t work out on the phone. But once lawyers get involved, then people don’t get to talk to each other and start saying things that aren’t true and attempt to shift blame based on how the press or public seem to be reacting. He took a lot of this on the chin and I don’t know that anyone deserves it. His movie seems to be a great priority to him and he wants to shift focus. I sure hope [the movie is] worth it — and that it’s a good one.

“I’m disappointed,” Sheridan adds. “It truncates the closure of his character. It doesn’t alter it, but it truncates it.”

Sheridan hints that John Dutton was never going to be around for the very end of the show, and that the conclusion of Yellowstone is unchanged from his original movie script. So Dutton will likely be — in the parlance of the series — “taken to the train station.” Or perhaps, I suggest, meet his fate in “a fuck-you car crash” (a phrase made famous after Grey’s Anatomy creator Shonda Rhimes killed off Patrick Dempsey’s character amid behind-the-scenes tension).

“I was killed in a fuck-you car crash!” Sheridan points out.

Oh, right: When Sheridan quit his modest role on Sons of Anarchy over being, as he saw it, woefully underpaid, his character was run over by a van.

“I don’t do fuck-you car crashes,” Sheridan says. “Whether [Dutton’s fate] inflates [Costner’s] ego or insults is collateral damage that I don’t factor in with regard to storytelling.”

Kevin Costner in Yellowstone.

Paramount Network/Courtesy Everett Collection

Speaking of which, another anonymous claim was that Costner had grown uncomfortable with the direction of his character and that Sheridan told him to “stick to acting.” Other actors on Sheridan’s shows have notably heaped praise on the writer and describe instances where he shows empathy for performers that reflects decades spent on the other side of the camera (when nervously auditioning for 1923, Julia Schlaepfer recalls Sheridan telling her “Hey, I’m an actor, all I want you to do is be you. Drop any notion of the character you ever had because you, to me, are Alex, you have all the qualities of this character, so just be yourself [and] I’ll read with you”). Sheridan does like his dialogue to be performed as precisely as written, but that’s hardly unusual.

“I never had that conversation with Kevin,” Sheridan says. “There was a time in season two when he was very upset and said the character wasn’t going in the direction he wanted. I said, ‘Kevin, you do remember that I told you this is essentially The Godfather on the largest ranch in Montana? Are you that surprised that the Godfather is killing people?’ What he’s clung to is [Dutton’s] commitments to his family and way of life. Dutton’s big failing is not evolving with the times — not finding different revenue streams [for the ranch]. Kevin felt season two was deviating from that, and I don’t know that he was wrong. In season three, we steered back into it.”

Sheridan adds: “And I recall him winning a Golden Globe last year for his performance, so I think it’s working.”

Asked if he could have done anything to prevent the situation from blowing up, Sheridan looks exasperated, like This reporter ain’t getting it.

“I didn’t do anything to begin with!” he says. “I don’t dictate the schedule. I don’t determine when things start filming. I don’t determine when things air. Those decisions are made by people way above me. My sphere of control is the content — that’s it. No production of mine has ever waited on me. Believe me, I begged [for more time] with 1883. I begged with 1923. Begged. Nope, ‘Airdate locked; for what we pay you, figure it out.’ And I don’t stand in a corner and go, ‘I’m not going to do it.’ “

Paramount chief McCarthy sees things a bit differently. He cites Costner’s “very tight window” and downplays the role of the studio’s streaming ambitions and scheduling moves. “We had a lead talent we adore, and [Costner’s] shooting four features back to back,” McCarthy says. “This Yellowstone chapter is closing sooner than we all wanted, but we feel good with where it’s going to end.”

Paramount announced that Yellowstone will return in November, which looks highly unlikely given the writers strike. (Sheridan insists he’s dutifully pencils down at the moment, and that he broadly supports the WGA’s efforts.) In a bit of good news for fans, however, Sheridan suggests he might make more than the previously reported six final episodes.

“If I think it takes 10 episodes to wrap it up, they’ll give me 10,” Sheridan says. “It’ll be as long as it needs to be.”

“WHAT DOES ‘GOD COMPLEX’ MEAN?”

Paramount’s hope is that Yellowstone isn’t really ending. Oscar winner Matthew McConaughey is in late-stage negotiations for a Yellowstone follow-up, a “new chapter” in the saga that will air on the streaming service (McConaughey is currently filming another project and declined to comment).

“He seems like a natural fit,” Sheridan says. “We had a few conversations over the years, and spitballed a few ideas. Then he started watching Yellowstone and responded to it. He was like, ‘I want to do that.’ And by ‘that’ he meant diving into a raw world clashing up against the modern world. And then I said, ‘Buddy, that we can do.’ “

Yet Sheridan surprisingly hints that the spinoff (which will have “Yellowstone’ in the title) might lean heavily, if not entirely, on a new cast and location. It’s tough to imagine Sheridan leaving behind a character like Beth, whom he clearly adores. But when asked specifically about shifting Yellowstone’s surviving characters to the new project, Sheridan replies, “My idea of a spinoff is the same as my idea of a prequel — read into that what you will.”

Meaning it’s a stand-alone story?

Sheridan nods. “There are lots of places where a way of life that existed for 150 years is slamming against a new way of life, but the challenges are completely different. There are a lot of places you can tell this story.”

Still, the project is in its early days. Sheridan says he has only “the broadest strokes” of the spinoff worked out.

He’s also planning several more Yellowstone prequels, which have not yet been announced. Paramount executives should brace themselves, as Sheridan expects these titles to become more expensive at a time when streamers are tightening their belts. By one estimate, Paramount is spending $500 million a year making Sheridan’s shows, which tend to cost at least $10 million to $15 million per episode.

“[The prequels are] time capsules of life in Montana as a microcosm of the world as a whole,” he says. “They’re big spectacles, and the more that you move into the modern era, the bigger that spectacle becomes. I know these are huge bets Paramount makes on me every time. I’m asking them to give me Game of Thrones season six money for what is essentially a pilot every year, and that’s a big ask. As long as I do my job well, and people don’t bore of the genre, I think there will be enough for many more [prequels] — three or four. Chris McCarthy trusts me, because I haven’t been wrong yet.”

Yet another Yellowstone-verse title, Sheridan’s previously announced Four Sixes series, is on hold given his newly acquired front-row seat to the sensitivities involved with the property. “That, for a number of reasons, needs a unique level of special care because this is a real place with real families working here,” he says. “You have to respect the lineage. I’ve told [the studio] to be patient.”

He also has two other upcoming titles: the historical Western anthology series Lawmen: Bass Reeves (starring David Oyelowo as the first Black U.S. marshal) and Land Man (starring Billy Bob Thornton as a Texas oilman).

There was one more recent claim about Sheridan in the press. An insider was quoted saying he has “developed a God complex.” So, have you?

“I wouldn’t think that, no, I don’t …” Sheridan pauses. “But you can find people — most of them line producers — who would feel that way. What does ‘God complex’ mean? I’m very blunt with every single person — the production staff, the studio, the network. I said, ‘Look, I invented this thing that I wrote down on paper and I’ve been entrusted to make it into a story that this network goes and sells. Your job is to try and get me there under budget.’ I don’t know that anyone ever said, ‘Yay, that TV show that got canceled after season one came in under budget.’ ”

He continues: “So if I’m parking 20 million people in front of a television, if I’m beating NFL Sunday Night Football routinely, I think the fact I wanted four cameras and worked late into Friday — I don’t think that’s a bad trade. My one rule with line producers and production people is: You don’t get to tell me ‘no,’ you get to tell me how much ‘yes’ costs, and then I decide where to pull that money from. It’s easy to tell me, ‘Taylor, you cannot have a helicopter for two days.’ That’s not the deal. I’m going to get a helicopter for two days. I’m going to swap this location to over here, and then I’m going to shoot this here, and I’ll squeeze this out there, and then it will end up costing the same amount of money. So if you want to call that a God complex, great.”

Sheridan considers. “And, by the way — and this is going to sound arrogant —”

No, please, go ahead.

“— but I don’t really give a shit what a line producer or some physical production person thinks. I care a lot about craft services and set decorators and assistant camera operators and people that are working their asses off for way longer than I work — and I work 16 to 18 hours a day. They’re doing it for $35 an hour. I really care what they think.”

“YOU WANT TO FIND BEAUTY SOMEWHERE”

The things Sheridan cares about — and what he doesn’t — sometimes align with his protagonists, who likewise tend to be determined bosses who are used to having things done their way. They feel deeply for their family, close friends and respective missions in life — never mind other people’s opinions.

Take Sheridan’s feelings about the Emmys. Sheridan has never been nominated, and his shows have been largely snubbed. Asked if he cares about winning the respect of his industry peers, Sheridan tells the backstory of his movie Wind River, which highlighted a grossly unjust law enforcement loophole.

“[Wind River] actually changed a law, where you can now be prosecuted if you’re a U.S. citizen for committing rape on an Indian reservation, and there’s now a database for missing murdered Indigenous women,” he says. “So keep your fucking award. Who’s going to remember I won an award in 10 years? But that law had a profound impact. All social change begins with the artist, and that’s the responsibility you have.”

Sheridan also cares more about romance than his gruff cowboy image might suggest. Whether it’s Beth and Rip in Yellowstone, or Spencer and Alexandra in 1923, Sheridan writes aching heartfelt relationships that seem downright taboo at a time when TV dramas are full of dysfunctional marriages and disposable hookups.

“I don’t want conflict in my own relationship, so I don’t like to explore that in stories,” he says. “There’s extreme conflict in my stories, but there has to be something to strive for — you want to find beauty somewhere. Everyone has been in a bad relationship. Who wants to go through the PTSD of watching that? I’d rather watch the fantasy of the relationship we all want.”

Then there’s the whole conservative label, which has never really fit. Yellowstone was unfairly branded a red-state show for years (it’s popular everywhere). Now Sheridan is amused to hear there’s been right-wing backlash declaring his shows “too woke” after Yellowstone introduced an animal rights activist character and 1923 devastatingly explored the historical abuse of Indigenous people. He didn’t see the online outrage himself since he stays off social media (“Let ’em hate!”).

Taylor Sheridan

Photographed by Emerson Miller

Yet his most politics-scrambling stance is his obvious passion for the environment. It’s one thing to advocate for the natural world like half of Hollywood does, quite another to put your overall deal on the line for a sizable chunk of the great outdoors. “This ranch looks like it did 150 years ago, and it’s a constant fight,” he says. “Business-wise, it was a terrible decision. But they’re just not making any more of this and someone’s got to take care of it. I felt a duty.”

To keep his operation thriving, Sheridan is avoiding John Dutton’s mistake and opening new revenue streams. In Austin bars, you can find the new Four Sixes-brand beer. Watch Yellowstone and you can see Beth touting the huge success of Four Sixes direct-to-consumer beef (“You sell out?!” she exclaimed), which actually launched right before the episode aired. Sheridan once pledged to make Four Sixes the most famous ranch in America. He just might become a tycoon in the process.

“The real impetus behind Yellowstone was always that if you’re the owner of an amount of land that vast, you’re kind of a king, and morality doesn’t apply,” he says. “I was surprised by the amount of political influence that we have [with the ranch]. I don’t know why I was surprised — I wrote it into Yellowstone. But what we do or don’t do can influence a market. So even though I wrote about John Dutton having that kind of influence, I never really fathomed myself having it.”

A final benefit of the mega-ranch: From Sheridan’s porch, the nearest public road is maybe a half-mile away. It’s a distance that might come in handy just in case any of his comments above rub someone the wrong way.

“If someone stands at my front gate and screams through a bullhorn and says what a piece of shit I am,” he says, “I still can’t hear them!”

“You don’t get to tell me ‘No.’ You get to tell me how much ‘yes’ costs.”

Photographed by Emerson Miller

This story first appeared in the June 21 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.