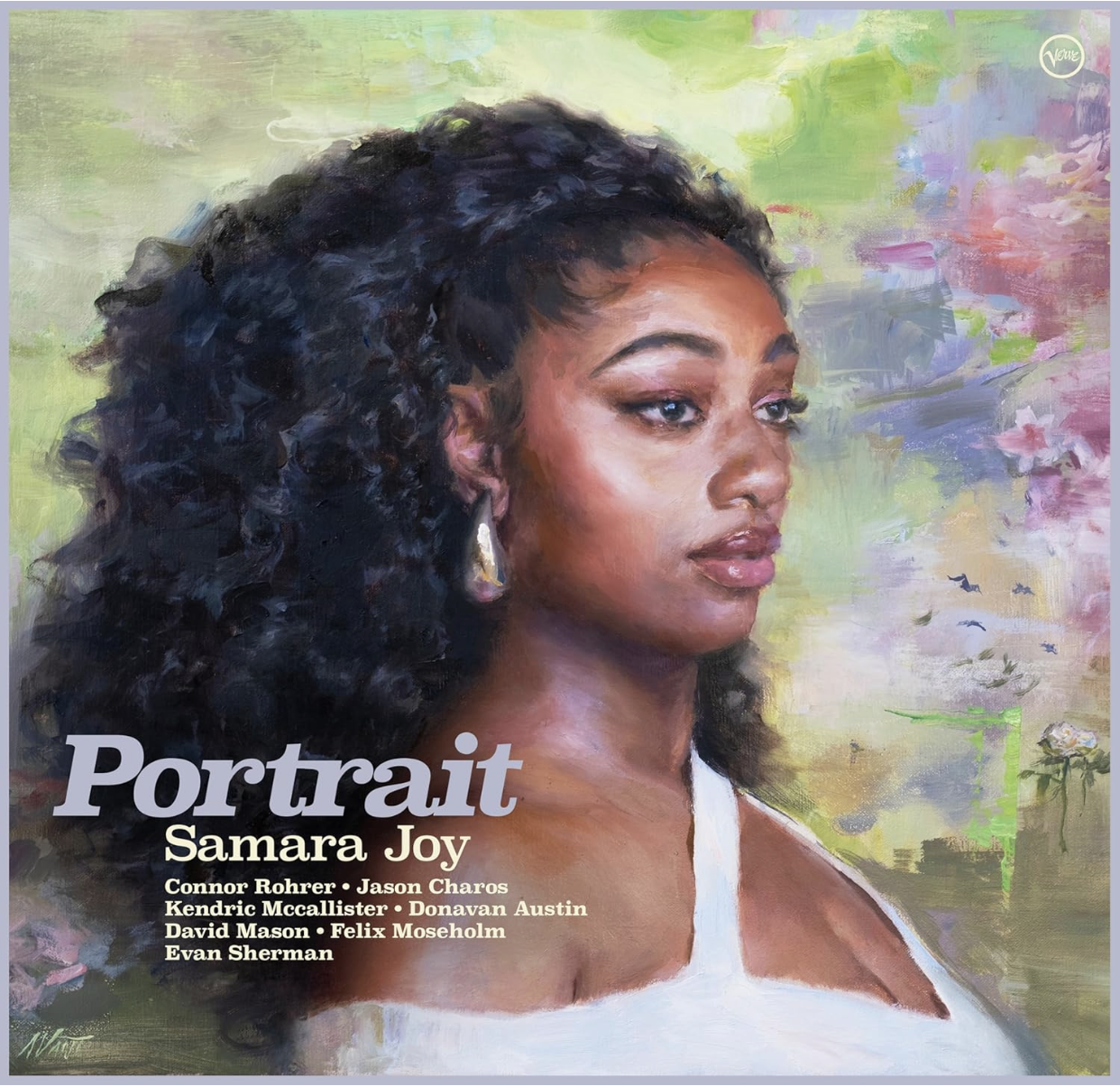

One day last February, inside a fairly plain, concrete-block building in Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Samara Joy stood in a glass booth. She closed her eyes, took a breath and said to herself, “This is it. And we’re gonna do it!”

More from Spin:

The Offspring Roll Back the Years on ‘Supercharged’

The Cure Are Feeling ‘Fragile’ On Latest ‘Lost World’ Single

The Decline: The Last Quarter-Century of NOFX in Their Own Words

And she started.

Only a dream to me you were, and then you slowly slipped away, she sang, unaccompanied.

This was in the studio of Rudy Van Gelder, where some of jazz’s greatest, most cherished recordings were made, Miles and Coltrane and Monk and Cannonball and thousands more. It’s where Joy, the young jazz singing sensation—she took the Best New Artist and Best Jazz Vocal Album Grammy awards in 2023 for the delightful Linger Awhile and the jazz performance Grammy honor early this year—chose to make her new album, Portrait.

She closes her eyes now, behind her big glasses, as she tells the story on a video call, tuning out the clatter around her in the hotel in Monterey where she is about to give a headline set at the California town’s famed jazz festival.

Those words she was singing? She wrote them. That’s a big deal. While she’s dipped her toes into lyric writing before and recorded some relative obscurities in the jazz catalog, she’s often thought of as a neo-traditionalist Great American Songbook type. She’s the new Ella Fitzgerald, the new Sarah Vaughan. Those have been the tags.

For this album, though, the Bronx native wanted to step forward with her own thoughts, her own emotions, and to that end three Portrait songs feature her words.

“I feel like I earned every single one!” she says of the lyrics. “I mean, it took so long.”

She laughs.

The melody she was singing, too, is a big deal. She didn’t write it, though. That’s Charles Mingus, a composition titled “Reincarnation of a Lovebird.” But her choice to write to a Mingus tune is another huge step toward expanding her scope and the perceptions about her. Mingus is known for the artistic and intellectual rigor of his material that could be daunting to musicians and listeners alike. For an audience expecting Gershwin or Loesser, this might be a shock.

So as she stood in the studio, starting to sing, she had a lot riding on this. And she’d put a lot of herself into it.

“It took so long to write those words, and to learn the melody. ‘Only a dream to me, you were…’ I had that for such a long time. That was the only idea I had. I was like, ‘I have to just focus on learning the melody first.’”

It’s a melody full of the twists and turns, shifts of cadence, leaps over intervals, typical of Mingus. It was Kendric McCallister, her trumpeter and the arranger of this song, who suggested the a cappella opening.

“I was like, ‘I just learned this song, and now you want me to sing it all by myself?’” She pulls her billowing hair back and laughs again. “Yeah, beautiful, 10 out of 10. I don’t know what else to say.”

It’s a magnificent performance, her rich voice traversing the melody’s contours with deceptive ease, leading to her finishing the verse reaching up, without stretching, turning the last lines of the verse into an aria.

Just as I close my eyes and pray for escape

I see your face

But sure as the sun

Dark as the moon

Swift as the breeze

Together soon we’ll be

Again with closing her eyes! In song, in the studio and in the telling. Back in the vocal booth, when she opened them after making it through a challenging two minutes that seemed like a year, she had one thought:

“Thank God I didn’t mess anything up!” she says now.

But she had little time to savor that, as around her out in the studio she saw seven musicians, her band, kicking into action to accompany her for the rest of the song—still a steep climb, but one they were making together.

That, as well, is a big deal. She’s worked mostly with trios and quartets, her voice out in front. This ensemble, her “little big band,” she calls it, realizes a dream she’s held of an expanded sound, an approach in which the musicians, with all of the arrangements on the album being done by band members, have collective freedom to explore. And this includes her as a vocalist, not just singing the songs’ words, but at times becoming one of the musicians with her voice as a truly integrated part of the group.

That’s showcased marvelously on the opening song, “You Stepped Out of a Dream.” There are a couple of times early on when she shapes a phrase or a word in a way that is utterly gripping, surprising in both imagination and skill. But the real treat of the song is in the middle instrumental part, where the band takes flight. Soon, though, Joy’s voice enters, wordless, just tones, blending so perfectly that it almost sounds as if she overdubbed a full choir to join the horns. But it was just her singular voice, live in the studio.

“That’s an illusion,” she says, laughing again. “The funny thing is that part wasn’t written for me originally. That was one that the trumpeter Jason Charos who arranged it added on. That’s what I love about this group. Everybody is thinking about music. You can be in a musical context with people for a year, or four years, and it doesn’t grow past a certain point. But in this group I’m really proud that everybody is thinking about music, everybody at all times, you know?”

As well, this group that she’s assembled gives the opportunities to explore repertoire beyond the standards, beyond the expectations. Not only is Mingus here, but Sun Ra as well. “Dreams Come True” is not one of his jazz-from-Jupiter out-there pieces, but rather a joyous swing jaunt. Still, it presents new horizons for her and challenges for her audience. There’s also “Now and Then (In Remembrance of…)” by Barry Harris to which Joy also wrote her own lyrics in tribute to the pianist-composer-educator, who died in 2021 at age 91 and was a beloved teacher of hers in the jazz studies program at State University of New York at Purchase.

And there are two completely new songs. One is the dramatic torch song “A Fool in Love”—you can imagine her singing it on a bandstand in an elegant gown in a 1950s noir film, an image that works for a lot of the album—with both music and lyrics written by her trombonist Donavan Austin. The other, “Peace of Mind,” is a co-write by her and McCallister which is paired in a medley with “Dreams Come True,” the new one’s dark, searching tone giving way to Sun Ra’s bright burst.

“I’ve known Kendric and Don since our freshman and sophomore years at Purchase,” she says. “Trying to figure out the chords for the original song, ‘Peace of Mind,’ was kind of difficult. I knew I wanted it to be suspenseful and dissonant. I wanted it to be sort of like a question mark. The fact that it doesn’t have any defined time was for a reason, which was of the uncertainty I felt in my life, the overwhelming feelings.”

Inspiration, she says, came from a 1961 recording of the song “In the Red” by one of her heroes, singer-activist Abbey Lincoln, who wrote the lyrics and also sought to push through perceptions of what a female jazz singer could be.

“You know, when I’m on the road and I’m singing some of the songs in my book for like the hundredth, or 2000th time I’m like, ‘I want to try something different.’ I’m listening to more music.”

She cites recordings of Thad Jones, Duke Ellington with Billy Strayhorn, the Jazz Messengers and Horace Silver as models of how much can be done even with a mid-sized group.

“I want to be able to try that,” she says. “I want to be able to experiment with that in my own way.”

This, all of this, is something to which she has given a lot of thought, clearly.

“This album is a pretty accurate representation of where I am at this moment,” she says. “There’s a lot of comparison, and rightfully so. I mean, I listened to Sarah, I listened to Ella, I listened to Betty [Carter] and tried my best to imitate them, make it so I could sing as easy as they could, access every part of my range without any hardship, execute any idea that came to my mind freely. Because that’s what I felt whenever I heard them. ‘Oh my! How did you even come up with that on the spot?’”

She’s only 24, but she knows that the image people have had of her is already entrenched.

“I think going into this album I was like, ‘Okay, no matter what I sing, even if I sing Mingus, people are going to say, “This sounds like something that I’ve heard” or maybe, “This reminds me of a time that is passed and gone.’” But with the responses I’ve gotten from people already, they’re like, ‘This doesn’t sound like just you with studio musicians. This sounds like a band!’ That’s the beginning. This seed has been planted where it’s like the repertoire has a possibility to expand.”

She continues, “This was the goal of the past year, ‘Who do I want to be?’ I don’t want to be a jukebox of standards, you know? I want to be able to think and actively participate in the music that I love in the context that I want to do it. I finally felt like I can travel with my own little big band and write in a way and sing in a way that will encourage others to realize how possible it is.”

With that, it’s hard not to note that the word dream comes up a bunch in the Portrait songs. Coincidence?

“Yes,” she insists, but quickly reconsiders. “Maybe it’s not. Maybe I was attracted to each of those songs for a reason. With ‘Reincarnation of a Love Bird’ I remember when I heard it and I put that word, those words to it, the first part of the melody. I was in Italy doing the Umbria Jazz Festival. I was in my room in Perugia, singing ‘Only a dream to me, you were,’ I was just singing and singing the beginning of the song. With the Sun Ra, ‘Dreams Come True,’ I was introduced to that song in my third year of college. And I was like, ‘Oh! I didn’t know Sun Ra sounded like this too!’ ‘You Stepped Out of a Dream’ came maybe a couple of months after I started this group. I was like, ‘I really like this one. I think we could have a nice, easygoing palate-cleanser in the set between Mingus and Sun Ra.’”

She pauses for a second. “I guess putting it all together it’s like, ‘Whoa!’ I always dreamed that I wanted to sing. I always dreamed that maybe I could eventually, hopefully, pursue a career in music, because I loved it so much and because it’s a part of my family legacy. But I never imagined I would be pursuing it in this way and that it would unfold like this.”

That family legacy includes her grandparents, Elder Goldwire and Ruth McLendon, who founded the noted Philadelphia gospel group the Savettes, and her father, Antonio McLendon, who played bass with gospel star Andraé Crouch for many years. (Her father, grandfather and other family members appeared on her 2023 holiday EP, A Joyful Holiday, most of them also appearing on a seasonal tour.) But she didn’t gravitate to jazz until high school, embracing it fully after enrolling at SUNY Purchase. It was a quick rise, though. By the time she graduated she’d won the Sarah Vaughan International Jazz Vocal Competition and signed a deal with Verve Records, recording Linger Awhile before even getting her diploma.

Her relatively quick success helped her see herself and her ambitions clearly and with caution.

“I think after the first Grammys I felt like there was a little bit of pressure to be part of that Hollywood world, to do what it takes to maintain and continue to uphold that moment, like we have to strike it. And I didn’t. I went right back on tour and I’m so glad I did because it gave me the opportunity to quickly refocus on what it is that I wanted to do.”

That first Grammy experience, she says, was “surreal,” just being there, walking the red carpet, seeing so many stars, going to the events and parties.

“I never imagined I would be on such a stage,” she says. “Just get a glimpse into Hollywood, getting a glimpse at, you know, Olympus, pretty much.”

She doesn’t want to live on Olympus? “Oh no!” she says. “Oh no! Too high up. I’ve got to stay close to the ground.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.